Set on St. Louis’ neglect-scarred north side, 3211 Blair Avenue barely stands out. With shards of rotting wood serving as the only reminder of a front porch, and windows shrouded in graying plywood, it’s one of more than 10,000 vacant buildings in the city.

Some of the city’s skeletal structures have burned-out, caved-in roofs. Others are wall-less. One rained red bricks onto the adjacent sidewalk, rerouting pedestrians into the street.

Neighbors have complained to the city that 3211 Blair Ave. is collapsing, posing a hazard to residents. Its owner owes hundreds of thousands in unpaid property taxes and has faced court judgments over this and other dilapidated properties.

Nearby, a three-bed, two-bath fixer-upper in the 3500 block of Blair Ave. sat similarly unloved until neighbors took the owners to court. The neighbors won and were able to acquire the deed. The renovated property sold in mid-March for more than $90,000, according to the rehabber.

Both buildings are in a part of St. Louis now flagged for major reinvestment. At least $37 million in American Rescue Plan Act funding, sent from the feds to combat the disastrous impacts of COVID 19 — and potentially $150 million more — is expected to flow into north St. Louis neighborhoods, according to the city’s mayor and an official with St. Louis Development Corporation, the city’s development arm.

Mayor Tishaura Jones, the city’s first Black woman mayor, has called the cash influx a “once in a lifetime opportunity” for the city’s north side, which also is the future home of the $1.7 billion western headquarters of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. That campus, called Next NGA West, is under construction in the St. Louis Place neighborhood of north St. Louis, and is expected to open to workers in 2026.

City officials have said residents of the six neighborhoods nearest the NGA campus will benefit from the planned investment, through a focused effort called Project Connect.

It is a moment decades in the making. Many residents see the federal funds, commitment from the Jones administration, and recent successes in the courts as a planetary alignment with the potential to finally bring about actual change.

Yet there is skepticism. Some long-time residents wonder aloud why the problem has persisted across multiple city administrations and question whether city leaders have done enough over the years to hold negligent property owners accountable. The residents fear that as government funds begin to flow, lax owners will cash in, selling their properties to the highest bidder and reaping a reward after years of dereliction.

Amid long-standing complaints from neighbors, the city is ramping up efforts to address vacant buildings such as 3211 Blair Ave. However, area residents fear negligent landlords will find rewards as development dollars move into the area. Image: Taylor McIntosh/St. Louis American

Few stand to gain as much as developer Paul McKee, whose company, NorthSide Regeneration, inked a deal with the city in 2009 to help redevelop a two-square-mile section of north St. Louis that includes parts of the Project Connect neighborhoods — including all of Carr Square and parts of JeffVanderLou, St. Louis Place, Columbus Square and Old North St. Louis.

NorthSide still foresees a “large-scale and holistic transformation” of the area, according to its website. But city officials and neighbors have complained that progress has moved at a glacial pace, with only a few structures actually completed.

As of this spring, NorthSide Regeneration owned more than 1,600 vacant parcels in the city, mostly in the Project Connect area. That includes nearly 230 vacant buildings, according to data compiled by the St. Louis Vacancy Collaborative, a coalition of community members, private and nonprofit organizations, and local government agencies working to reduce the negative effect of vacant property in St. Louis.

That’s nearly half — 46% — of the vacant buildings owned by the top 10 private owners listed by the Collaborative.

A list of resident concerns in 2021 included nearly three dozen “building collapsed” complaints in the Project Connect neighborhoods. Seven reported properties were listed as being owned by NorthSide Regeneration, the most for any one property owner.

The city issued “structural condemnation notices to six of the properties, including NorthSide Regeneration’s vacant property at 3211 Blair, which was condemned in June 2013, according to the Vacancy Collaborative. A condemnation notice means the property is not safe for habitation. The building owner has 30 days from the notice date to make progress — obtain a building permit to demolish or repair — and 10 days to file an appeal, according to the city’s Building Division.

Most of the buildings, including 3211 Blair, were still standing as of mid-June, according to an inspection by The St. Louis American and Type Investigations.

An official with the city’s Building Division said photos of 3211 Blair on file in the department “don’t show that it poses an imminent danger to the public, therefore the City of St. Louis funds will be used for more urgent [collapsing structures] in the ward.” She added that the case has been “referred to court.”

In the JeffVanderLou neighborhood, as of this spring, nearly 60 NorthSide properties were condemned, according to the Vacancy Collaborative.

Darryl Piggee, McKee’s attorney, did not respond to questions about specific properties, so it’s impossible to determine whether NorthSide took action.

In an emailed response to questions from The American and Type Investigations, Piggee instead focused on the significance of McKee’s decision to invest in the area. “Mr. McKee decided to invest where no one — not third parties or even the city’s development agencies — were willing to go for almost six decades,” he wrote. “Since making that decision, Mr. McKee has expended more than $8 million toward real estate taxes, grass cutting, demolition and maintenance charges.”

“We challenge you to find anyone whose financial commitment to North St. Louis approaches that level, or who has expended these kinds of sums on vacant lots and abandoned property in the long-ignored North side, the City included,” he said.

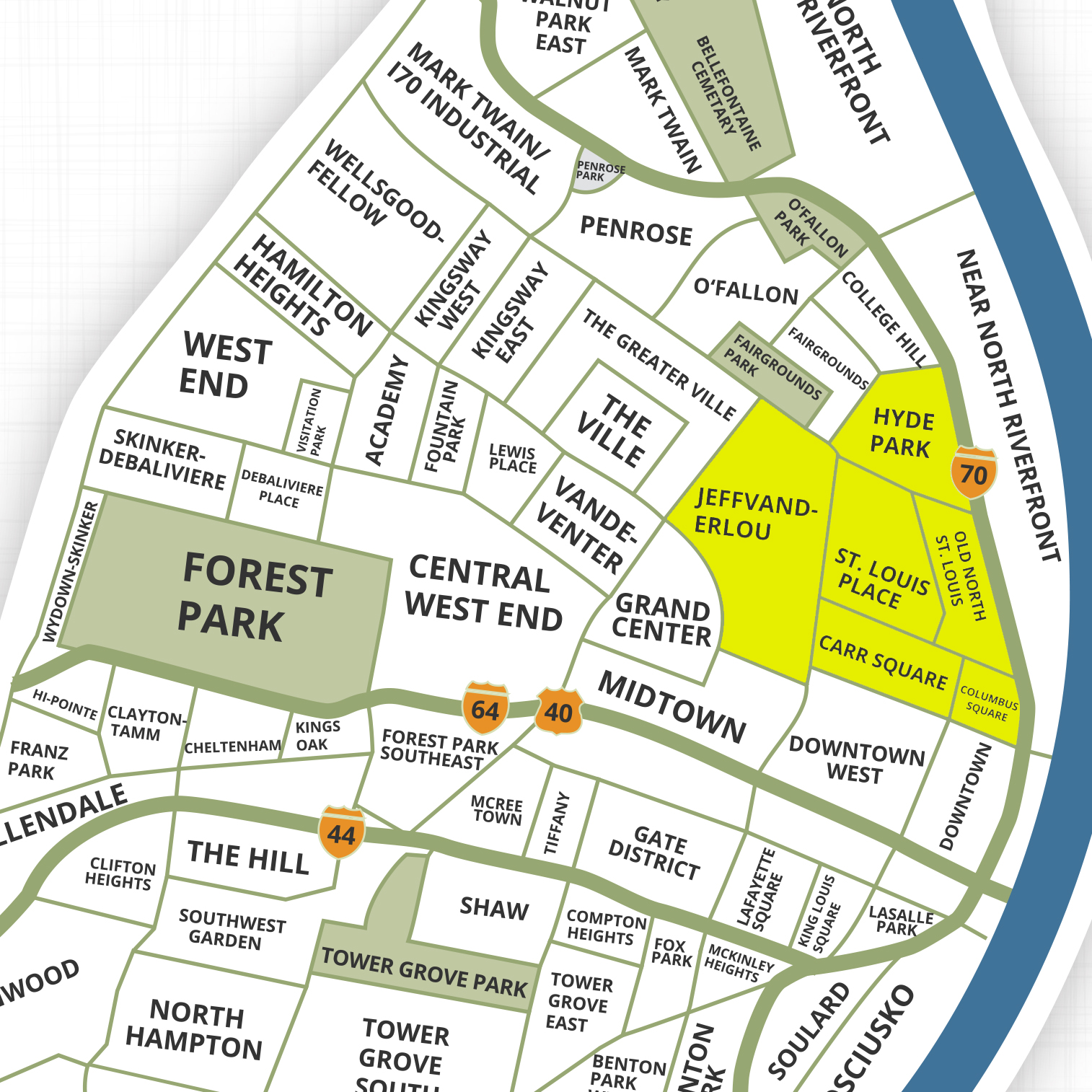

As part of Project Connect, city officials have embarked on a listening tour of the six neighborhoods — Hyde Park, St. Louis Place, JeffVanderLou, Old North St. Louis, Carr Square and Columbus Square — seeking resident input on how the federal rescue funds should be spent.

In a survey the city released in June, 2,108 respondents who live in St. Louis selected “addressing vacancy” as a top priority, one of the highest tallies for any specific category.

St. Louis firefighters battle a blaze at a vacant building in North St. Louis in early July, 2022. About 40% of department calls are to vacant structures. Image: St. Louis Fire Department

That concern was echoed by nearly a dozen community leaders and neighborhood advocates contacted by The American as part of a months-long reporting project with Type Investigations.

“Vacant, uncared-for property and land, it’s just not appealing,” said Andre Logan, pastor of the Thessalonian Missionary Baptist Church, a predominantly Black congregation in the JeffVanderLou neighborhood. “It’s not desirable to the community, especially when it’s next to a homeowner’s house. I mean, it’s just not good. Some of the properties are dangerous. Some of them have fallen down.”

“Why has it been allowed to happen?” he asked. “Why is a very good question; that I don’t know. That’s the million-dollar question.”

While politicians for years have promised to address the vacancy problem, the push took on new urgency earlier this year when St. Louis Firefighter Ben Polson was killed fighting a fire in a vacant home in north St. Louis. The roof collapsed as Polson was checking to make certain no one was trapped inside.

An estimated 40% of calls answered by the St. Louis Fire Department are to vacant structures, according to Fire Captain Garon Mosby.

Beyond the fire danger, the vacant properties can drain city resources.

As of mid-July, Northside Regeneration owed at least $320,000 in property taxes on its vacant buildings alone, not counting taxes owed on hundreds of empty lots, city records show.

As of July, the Vacancy Collaborative reported that citywide, property owners owed $4.9 million in unpaid property taxes; $7.6 million in billed forestry maintenance fees; and $3.5 in unpaid vacant building fees and fines for a total of $16 million.

The site does not break down the fees by property owner.

Asked about the unpaid taxes, Piggee did not comment on specific properties but said, “We pay our taxes.”

When asked if property owners behind in taxes and fees would be required to pay up before participating in the coming development, a spokesman for the mayor’s office directed the question to the Development Corporation, which did not respond.

The $1.7 billion western headquarters of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, called Next NGA West, is taking shape in North St. Louis. Six neighborhoods around the campus are in line to receive stepped up investment, in part through federal COVID relief funds. Image: Courtesy of NGA

The idea of neglectful property owners cashing in doesn’t sit well with homeowners like G. Fatimah Muhammad, who, along with husband Donald Harden, chose to move to the north side’s Hyde Park neighborhood about 20 years ago.

“These properties have sat vacant for years,” she said. “Some of the owners opted [for] paying citations and continuing to let the building remain in disrepair and [be] a continuous eyesore and danger to the community. Others let the citation fees and back taxes accumulate and still did nothing to eliminate the nuisances, waiting for a real estate payday.”

Decades of disinvestment

St. Louis’ vacancy problem has unfolded over decades and stood at 24,923 vacant parcels in total as of July, according to the estimate from the Collaborative’s website. The highest concentration of vacancies is in the city’s northern stretches — occupied largely by low-income, people of color.

That citywide tally includes an estimated 10,579 vacant buildings and 14,344 vacant lots, according to the Collaborative, which draws its data from the St. Louis Building Division, the Assessor’s Office, the Division of Forestry, and the Citizens’ Service Bureau.

When looking at “concentrated” vacancies, such as those found on the north side of the city, St. Louis is one of the most vacancy-plagued cities in the nation, according to the Vacancy Collaborative.

California-based ATTOM Data publishes a quarterly vacant property report. Of the 100 U.S. zipcodes with the highest percentage of vacant properties this winter, five of them were in St. Louis, more than in almost any other U.S. city.

The blame for the city’s gap-toothed visage lies with many of the usual suspects: lackluster regional growth, racism, and chronic disinvestment, according to residents and the countless news articles that have been written on the vacancy problem.

St. Louis city has seen a significant drop in population — down 6% from 2010 to 301,578, according to the 2020 Census.

At the same time, the number of Black and mixed-race Black city residents dropped by 15% to 137,059, according to data from Census.gov. Many left north St. Louis for the suburbs in north St. Louis County, while some moved into the city’s revitalized central corridor and near south side neighborhoods, according to Glenn Burleigh, community engagement specialist for St. Louis’ Equal Housing & Opportunity Council.

In some cases, Burleigh said, that left behind vacant homes, including in the Project Connect neighborhoods.

Of the 10 neighborhoods with the most vacant lots and buildings, according to the Collaborative, three are in the Project Connect area — JeffVanderLou, St. Louis Place and Hyde Park.

Beyond population drops, Burleigh sees another culprit behind the bumper crop of vacancies: redlining. That federal government-backed value-killer dates back decades, and has pummeled many major urban areas including St. Louis.

“You’ve got to remember that … what society has done, has essentially made it virtually impossible for homeowners in majority-Black neighborhoods to keep up their homes,” Burleigh said, noting the inability of homeowners in those areas to tap into home equity loans at the same rate as homeowners in white areas.

“If you’re not able to access the mainstream banking and finance things, [as] the majority white areas are, you can’t do things that are just considered normal as far as using equity to finance repairs and maintenance and stuff on your home.”

Six north St. Louis neighborhoods are slated for targeted development from the city in part to address blight. Three of the neighborhoods have among the city’s highest concentrations of vacant properties. Image: Dan Brassil/James LeBine

St. Louis suffered from the same pernicious policies, in effect at the federal level from the 1930 to the 1960s, that blocked the Federal Housing Administration and later the Veterans Administration from insuring loans in predominantly Black areas, according to Next City, which covers solutions to urban issues.

Insufficient funds for upkeep, titles with expensive liens, and owners who die without a will have forced some families to walk away from properties that otherwise could have been used to provide generational wealth.

For some developers, it represented the perfect buying opportunity.

‘Comprehensive regeneration’

The plan was impressive.

NorthSide Regeneration would spend $8 billion over 23 years to replace a decaying city core with a brand spanking new one complete with 10,000 homes, parks, schools and churches. Also on the drawing board was 3 million square feet of office space, 2 million square feet for retail, 1 million square feet for tech, a primary care hospital and three major employment centers, according to the NorthSide website. NextSTL, a website that covers St. Louis development issues, noted plans for 240 hotel rooms, a $35 million recycling center along with thousands of market-rate residences.

NorthSide Regeneration owned 1,999 properties at peak ownership, according to St. Louis Public Radio.

“Today, the area is on the cusp of a remarkable and comprehensive regeneration that would mean jobs, opportunity, economic self-sustenance and minority wealth creation,” according to the NorthSide Regeneration website.

Buying into the vision, and with a dearth of competing ideas on how to revitalize the area, St. Louis agreed in 2009 to let the company develop the area through a $390 million tax increment financing district, according to a 2018 letter from the city. In the TIF district, taxes on future gains in property values would be used to help pay for improvements in the area.

NorthSide also received $43 million in tax credits, according to the city letter. The credits were offered through a law that a member of McKee’s legal team helped write.

Piggee, McKee’s attorney, said “nearly a decade before Mr. McKee got involved,” a report on the city’s 5th Ward, which is on the north side, noted that the area could not expect meaningful progress without the incentives ultimately awarded to Mr. McKee and the large scale site control and planning he proposed.”

A 2018 letter from NorthSide to the city called McKee’s plan for the neglected area “unprecedented risk taking.” It cites a brief submitted by the Board of Aldermen’s attorneys stating that by the fall of 2009, “Northside had borrowed $27.6 million which was invested in the redevelopment effort, all of which was guaranteed by McKee personally.”

McKee sold the city more than 330 parcels, needed to make room for the Defense Department’s NGA project, according to a settlement statement. Piggee described it as 56 of the nearly 100 acres the city needed for the NGA.

In time, though, the city became concerned.

Despite the grand promises, lots remained vacant and untended. Property taxes went unpaid. No major developments opened before 2019 – nearly 10 years after the initial pact was signed. So the city terminated the agreement.

In the city’s 2018 letter, signed by then-City Counselor Julian L. Bush, the city declared that NorthSide was in default on the development agreement adding, “It is time to face facts. After a decade, the promised redevelopment has not come, nor is there any indication that it will … Land lies fallow … Vacant buildings remain dangerous and unsecured.”

As of 2018, the city said in its letter, NorthSide owned at least 205 buildings that had been cited for building code violations.

In its rebuttal to the city, NorthSide accused the city of getting in the way of development in the area stating: “The City Parties have failed to cooperate — and, in fact, have actively worked to undermine — NSR’s development of projects in the vicinity of the NGA Site.”

“Mr. McKee invested even though he faced inexplicable interference by the City, and a series of legal challenges, all of which unnecessarily delayed progress and required the use of valuable resources to litigate and negotiate with the City and third parties,” said Piggee.

And he disputed that progress was slow, adding, “We had satisfied all of our development obligations under our redevelopment agreement when the City terminated our development rights. … We believe that the termination was completely unwarranted and unlawful.”

Bank of Washington, a major lender for the NorthSide project, filed suit in 2018 against the city’s Land Clearance For Redevelopment Authority — which oversees many aspects of public and private real estate development in St. Louis — accusing the city, in part, of unfairly pulling out of the project.

A June entry in the court file noted that both sides reported that attempts at mediation were “unsuccessful,” The case is headed to a jury trial next year, according to the file.

The city’s withdrawal came even as NorthSide moved forward on plans for the first two major projects in the area: a ZOOM gas station and a 20,000-square-foot grocery store called GreenLeaf in Columbus Square, both of which opened in 2019.

McKee has acknowledged that some citizens, as well as city officials, have expressed concern.

“Usually when we get complaints, we beg the people to call us direct, but they call the city because they think they’re getting us in trouble,” McKee told St. Louis Public Radio in 2018. “No matter how hard we work to get them to call us direct,” people keep calling inspectors and the Citizens’ Service Bureau, he said.

Patricia Dees, chair of the St. Louis Place Community Association, said she and her neighbors have reached out to NorthSide, adding, “we were not always met with the best responses.”

Standing in a vacant lot listed as being owned by Northside, she said now residents keep detailed records on all attempts to get something done, and pass that information on to the city via a Neighborhood Improvement Specialist for Ward 5.

Many residents found it easier to take action themselves and were actually mowing and cleaning the NorthSide lots, she said.

And, increasingly, residents began to turn to the courts.

Legal aid

Muhammad, of the Hyde Park association, said she and husband, Donald Harden, were excited about buying one of the “beautiful vacant homes” in the Hyde Park area two decades ago.

In 2002, the couple paid $1,500 for a 3,000 square-foot property in the inventory of the city’s Land Reutilization Authority, the owner of last resort after properties don’t sell at tax sales.

The 140-year-old four-bedroom, five-bath property would become their retirement home, but it needed work, she said. Unable to secure a rehabilitation loan, the couple funded the rehab with money from their own pockets.

In 2017, Muhammad came out of retirement to found the Hyde Park Neighborhood Association of North St. Louis, in part to deal with the vacancy curse.

“I have come out of retirement to do the work that is needed in our community,” she said. “I do it with love for my people, the community and the betterment of all. No one heard the voices of the community until now, that’s why I do it.”

Patricia Dees, chair of the St. Louis Place Community Association, stands in a lot city records say is owned by NorthSide Regeneration. The lot was recently cut but Dees said at times neighbors have to mow vacant lots themselves. Image: Wiley Price/St. Louis American

To help spur progress, the neighborhood association turned to Legal Services of Eastern Missouri, Inc., which in 2018 brought to St. Louis the Neighborhood Vacancy Initiative, a spinoff of a similar program born in Kansas City that uses the courts to help break up the logjam that keeps vacant, decaying properties from being sold to would-be developers.

Between 2018 and 2022, the Hyde Park Neighborhood Association filed at least a dozen lawsuits against neighborhood property owners, according to a search of filings in Missouri Courts. It’s been among the most active neighborhood groups in taking negligent property owners to court.

Its lawsuit list includes the case against the former “absentee” owner of 3519 Blair Ave.

“I definitely remember this being one of the worst houses I have ever seen,” said Peter Hoffman, managing attorney for the Neighborhood Vacancy Initiative of the Legal Services group, describing it as “terrible, owners long deceased, heirs unknown … If the neighborhood hadn’t intervened, this house may very well not be standing anymore.”

At Hoffman’s urging, developer and real estate broker Tenesia Looney-Brown looked at more than a dozen properties in north St. Louis, several of them owned by NorthSide Regeneration and many of them she felt “needed to be torn down.”

The property on Blair was “horrible too,” but she felt, “this is the lesser of all the evils … Altogether, I probably spent about $160,000 on it and I sold it for” $93,000, she said. “Our main focus everywhere we go is the urban core and revitalizing it.”

At 1514 Mallinckrodt Street, a former multi-family home built in 1892, “the entire rear of the building had fallen to the ground,” Muhammad said. The Vacancy Collaborative listed eight “major” city code violations at the property before it was demolished in recent years.

The new owner of the land, the St. Louis-based nonprofit Dream Builders 4 Equity, plans to use the property as the site of its first ground-up build. The organization, co-founded by Michael Woods, aims to rehab at least 25 vacant properties to be sold to first-time homeowners, and provide free home renovations worth up to $10,000 for 25 seniors.

“I wanted [Dream Builders] to be the change … to be that first investment or to be that person or a part of some group that inspires other people to really see and understand that this is needed, like it has to be done,” said Woods.

He’s currently rehabbing 1522-24 Mallinckrodt Street, “one of the oldest properties in St. Louis,” according to Preservation Research Office. The 1850s era structure was badly damaged by fire in 2005.

Muhammad cited progress at the two Mallinckrodt addresses as court-aided wins for the community.

Partnering with Legal Services of Eastern Missouri allowed Muhammad to find rehab partners able to restore historic homes in the neighborhood. “Now, these properties are being rehabbed into affordable beautiful homes,” she said.

“These are the real stories. … the successes, the wins,” she added. “The community has been so excited about the processes as we work, block by block, to bring about change in our community.”

In an area where residents often are portrayed as victims, Muhammad sees the legal strategy as evidence of residents’ collective agency.

“Residents are joining together, taking back their power,” she said. “Working and collaborating with city departments, neighborhoods, other organizations and businesses. Working as a unit with transparency has been our focus.”

The nonprofit Dream Builders 4 Equity is working to rehabilitate vacant buildings in North St. Louis. The team includes, from left, Colin Nelson, construction manager; Jessica Gaines, construction manager; Michael Woods President & CEO; Lucy Redd. Director of Operations and DeMarkus Turner, Media & Youth Support Specialist. Image: Wiley Price/St. Louis American

But there is still much work to do. And that raises questions about current north side revitalization plans.

At least 30 vacant properties in Hyde Park are owned by NorthSide Regeneration, McKee’s company, according to the Vacancy Collaborative database.

A city database reviewed by The American and Type Investigations showed that NorthSide Regeneration still owed 2020 and 2021 taxes for at least 222 of the company’s vacant buildings in the Project Connect neighborhoods, as of mid-July. That’s not counting taxes owed on vacant lots.

As recently as March, it also owed property taxes for 2019 for most of its vacant parcels, including the Blair property, according to data from the Collaborative. Under state law, tax collectors can start procedures to collect delinquent taxes within one year, but the city typically files suit to collect taxes after a property has been three years behind on taxes, according to the St. Louis Collector of Revenue. Some owners, like NorthSide, seem to pay just one year’s derelict taxes at the last minute, to avoid legal action.

Piggee, McKee’s attorney, did not respond to questions about unpaid taxes at specific properties.

City officials did not respond to questions regarding property owners who still owe taxes for 2020 and 2021. We also asked what neighbors are wondering — whether these same owners will be allowed to profit from the revitalization. The city did not respond.

None of the dozen lawsuits filed by the Hyde Park Association was against NorthSide. Muhammad did not say why.

But the city’s Department of Public Safety, which contains the Building Division, has taken the developer to court at least six times since 2018, securing judgments totaling more than $4,500. The amount of delinquent tax, penalties and fees due on a piece of property at the time of a court judgment is included in that judgment, according to Tom Vollmer, a deputy with the Collector of Revenue department.

Hoffman, of Legal Services’ neighborhood vacancy initiative and the lead attorney in many of the court cases, declined to discuss specific cases. But he, like the residents interviewed, expressed hope that the city might be moving toward substantive change. “I believe there’s a commitment from this current mayor, to try to make a dent in this problem,” Hoffman said.

In her first State of the City Address in April, Mayor Tishaura Jones — who describes herself as the “first mayor in over 20 years to be born, raised and still live in north St. Louis” — said she would like to see $150 million in American Rescue Plan Act funding spent on the north side of the city. That’s beyond the $37 million in ARPA money already committed to the area.

The aim is to bring about change.

“This change looks like fewer boarded-up buildings and crumbling vacant [structures] on our blocks,” she said. “We must stabilize or renovate vacant buildings and make them neighborhood assets instead of deadly risks to our residents and our firefighters.”

She told The American and Type Investigations that “is accurate” to note the city has not done enough in the past, but the city was now determined to “hold neglectful property owners like Northside Regeneration accountable.”

Still, she said, progress may be slower than some would like.

“Fixing a decades old issue won’t happen in a day, or even a year, but we have started making a concerted effort to reverse these historic wrongs,” she said in an email to The American. “In this year’s budget we’ve included $6 million to help address vacant buildings, including rehabilitation or demolition. This is in addition to funding and support from the state and private organizations.

Jones divided her proposed $150 million spending plan — which must be approved by the Board of Aldermen and the Board of Estimate & Apportionment — into three categories, including one labeled “neighborhood transformation.”

That includes “capacity building, vacancy [abatement]… environmental justice” and improving housing accessibility. That category would get up to $70 million — nearly half of the $150 million Jones is pushing for.

Hoffman called the vacancy issue “an enormous problem,” adding, “it’s going to take years to fix. You know, it’s been 50 years in the making. It’s not going to be something that’s going to go away overnight. But hopefully, the thing that I think that maybe people are more optimistic about, I know I’m optimistic about, is that there are federal funds that are now available.”

He said the problems in the Project Connect neighborhoods won’t be solved by investment alone.

“In most city neighborhoods, the owners of vacant nuisance properties are varied,” he said. “Many of the blighted properties around the NGA site are due in large part to one particular bad actor. The key to addressing those [resides] in addressing that particular owner.”

Asked if he was referring to McKee, Hoffman said, “Yes. I think anyone reading this will know who I’m referring to.”

For residents like Dees, of the St Louis Place Community Association, the thought that negligent property owners might be in line for hefty profits brings with it “a sense of frustration.”

“It’s derelict properties around that nobody is taking care of,” she said. “And all of a sudden, the properties will get sold at this astronomical amount. And then here I have been, cutting your grass or cleaning up trash or whatever else to keep my property from looking a mess. So, you know, there is a lot of animosity.”

Without commenting on specific properties, Piggee said, the company has “had to devote precious resources to defending frivolous litigation and inexplicable in-fighting with the City. We are making every effort to ensure that demolition proceeds where necessary to protect the public.”

Dr. Annessa Blackmun, who opened a business in the Old North neighborhood in 2013, thinks the focus on McKee has taken the spotlight off of the city and its responsibility to address the problem.

“I really want to take the focus off of Mr. McKee and put it back on the city and what kinds of plans or resources or incentives are there to get these parcels not to be vacant. You know what I mean? Because at some point, it’s like this big circle and it all goes back to this supposedly horrible bad guy and I don’t know if that’s good enough anymore for me.”

So far, officials have yet to articulate a specific plan. Leaders in the city’s development corporation say they plan to address multiple issues in north St. Louis, from development to the threat of gentrification.

Many of the specifics, however, have yet to be determined. Listening to residents and crafting a plan is expected to take two years, according to Lance Knuckles, who last fall joined the St. Louis Development Corporation as director of strategic growth and development.

He did not have a total figure for how much will be spent in the Project Connect area but outlined some funding sources.

The city is planning on using $20 million in ARPA funds to support affordable housing in north St. Louis and $5 million for grants to small businesses negatively affected by COVID, he said.

Another $2.5 million will go to small business lending for community development corporations and neighborhood organizations across north St. Louis.

Meanwhile, residents like Dees see in the concurrent activity of the SLDC, the Vacancy Collaborative, Legal Aid, and others, as threads which — if taken together — could form a lifeline.

“I’ve got all these people woven and braided together in this rope,” said Dees. “And I’m holding on to this rope … by a thread, praying that they are going to do what they promise us that they’re going to do.”

Research assistance by Paco Alvarez and Nina Zweig of Type Investigations. Produced with support from Report For America.