For all of Tom Schweich’s accomplishments — degrees from Yale and Harvard, partner at an international white-shoe law firm, chief of staff to three U.S. ambassadors, second-ranking international law enforcement official at the State Department, professor, author and twice-elected auditor of the state of Missouri — the first thing you noticed about the guy was that he sure didn’t look like a politician. He probably stood five foot four on a good day, with a receding hairline, sunken eyes and big jug ears. He never weighed more than 140 pounds, partly due to the fact that he suffered from Crohn’s disease, a gastrointestinal condition that diminishes appetite. His suits draped over his slight frame and his ties hung down to his fly. Harry Otto, who served as Schweich’s number two in the auditor’s office, remembers first laying eyes on his future boss and thinking, “He doesn’t look like he could fight his way out of a wet paper bag.”

Schweich didn’t act much like a politician either. He stepped on his applause lines. He let reporters into the little corners of his life, his collections of rare coins and autographed Hollywood memorabilia. Nor was he temperamentally suited for the rough-and-tumble of electoral politics. Tightly wound and thin-skinned, he took slights and insults personally and spoke his mind with refreshingly little filter. “Tom never thought about what the reaction would be,” says his former campaign treasurer, Joe Passanise. “He would just act.”

That’s certainly what he did on the evening of January 28, 2015, when Schweich announced his candidacy for governor at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, in a speech the likes of which Missouri had never heard. The 54-year-old lifelong Republican told the audience that Missouri’s government had been held captive by lobbyists, political consultants and outside interests. Corruption and cronyism were endemic. Over the objections of his advisers, he singled out his opponents by name: His main Republican rival, former Missouri House speaker Catherine Hanaway, whom he referred to as “Catherine Layaway,” had been “bought and paid for.” The Democratic favorite, Attorney General Chris Koster, who allegedly gave preferential treatment to corporations after taking donations from those same companies, was the “poster child for selling his office to contributors.” (A Koster spokesperson denies any wrongdoing by Koster and says the campaign has “implemented what we believe is the strongest conflict of interest policy in the nation.”)

Schweich’s sharpest barbs, though, were saved for St. Louis mega-donor Rex Sinquefield, the wealthy investor and closest thing Missouri has to its own Koch brother. The “Sinquefield machine,” Schweich warned, sought nothing less than the takeover of the state. Despite representing opposing parties, Koster and Hanaway had each counted Sinquefield as their top contributor over the span of their careers. “Rex Sinquefield is trying to buy himself a governor,” Schweich said. “You have my word that as long as I can stand on these two feet, I will fight to keep the Republican Party from becoming the Rex-publican Party.”

It was a startling thing to behold, a campaign rollout speech built around shaming the state’s largest donor and two of its most well known politicians. And yet this was the essence of Schweich’s candidacy: He was running as “a true anti-corruption expert.” A Kansas City Star columnist hailed him as “the disrupter.” Schweich’s entry into the governor’s race signaled the beginning of a fight not just for Missouri’s highest office, but for the soul of the state’s body politic. And despite his unassuming stature and jittery disposition, Schweich looked ready to wage that fight to the end.

But in truth, Schweich was coming apart. In the weeks following his speech, he became obsessed with what he believed was an “insidious” effort to damage his name and undermine his campaign, an obsession that hounded him until he took his own life. Mental health experts agree there is almost never a simple answer for why someone chooses to commit suicide, but in an effort to better understand the tragedy, I spoke with nearly 50 people who knew him (some of whom spoke on the record for the first time). I also obtained previously unpublished private notes, emails and texts that provide new details of the events leading up to Schweich’s death.

At 9:41 a.m. on the morning of February 26, 2015, Schweich left a voicemail for a journalist he knew well, Tony Messenger, then the editorial page editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He told Messenger he wanted to lay out allegations of what he saw as political harassment and bigotry, and he said he’d provide evidence to support them:

“Tony, this is Tom Schweich calling. If you could have a reporter here at my house at [address] at 2:30, I’m willing to speak to both the Post-Dispatch and to the AP only about this matter. I would give a pre-prepared statement, which we would videotape, and then answer questions from your reporter. This is only for you two, and so I hope you’ll not make it known that I’m giving this. But give me a call and let me know if you can have somebody here at 2:30. To me, this is more of a religion story than a politics story, but it’s your choice who that reporter is. Thanks. Bye.”

Schweich never delivered his statement, so there’s no way to know what exactly he planned to tell the reporters. But the incidents, real or perceived, that preoccupied him at the time were well-known among his inner circle: That the chairman of the Missouri Republican Party had led an anti-Semitic “whisper campaign” against him; that Rex Sinquefield was bankrolling his opponents to scare him out of the governor’s race; that his party’s most powerful consultant — the man now running Sen. Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign — had crafted a vicious ad mocking Schweich’s appearance that aired on the eve of the largest Republican event of the year. Over the previous months, as the pressure mounted, his closest friends and advisers had urged him to brush it all off, to rise above the fray. Schweich, out of self-righteousness or anger or both, felt he couldn’t let the attacks against him go unanswered.

In his second-floor bedroom, soon after his call to Messenger, Schweich overheard his wife, Kathy, on the phone, and asked, “Who are you talking to?” It was Martha Fitz, a longtime family friend and confidante. Schweich took the phone and told Fitz about his plans to go public. Fitz tried to talk him out of it. “What’s your goal?” she asked. “Your goal is to be governor. We are not against you, Tom. We are trying to help you and give you our best advice. We can’t all be wrong.”

Schweich heard those words and, before throwing the phone onto the bed, said, “I’m going to kill myself.”

His wife picked up and apologized. She faced away from her husband, who had knelt down into the closet.

“Does he say stuff like that?” Fitz asked.

“Sometimes,” Kathy said, then gasped. “Oh my god! He shot himself!”

Schweich arrived in Jefferson City, the state capital, to begin his first term as state auditor in 2011. On a high bluff overlooking the gentle Missouri River, the 262-foot-tall Roman renaissance-style Capitol building, carved out of Carthage, Missouri marble, dominates the city’s skyline. It is a striking view, inspirational even. But what Schweich quickly discovered was that day-to-day life in Jeff City left you feeling like you needed to take a shower.

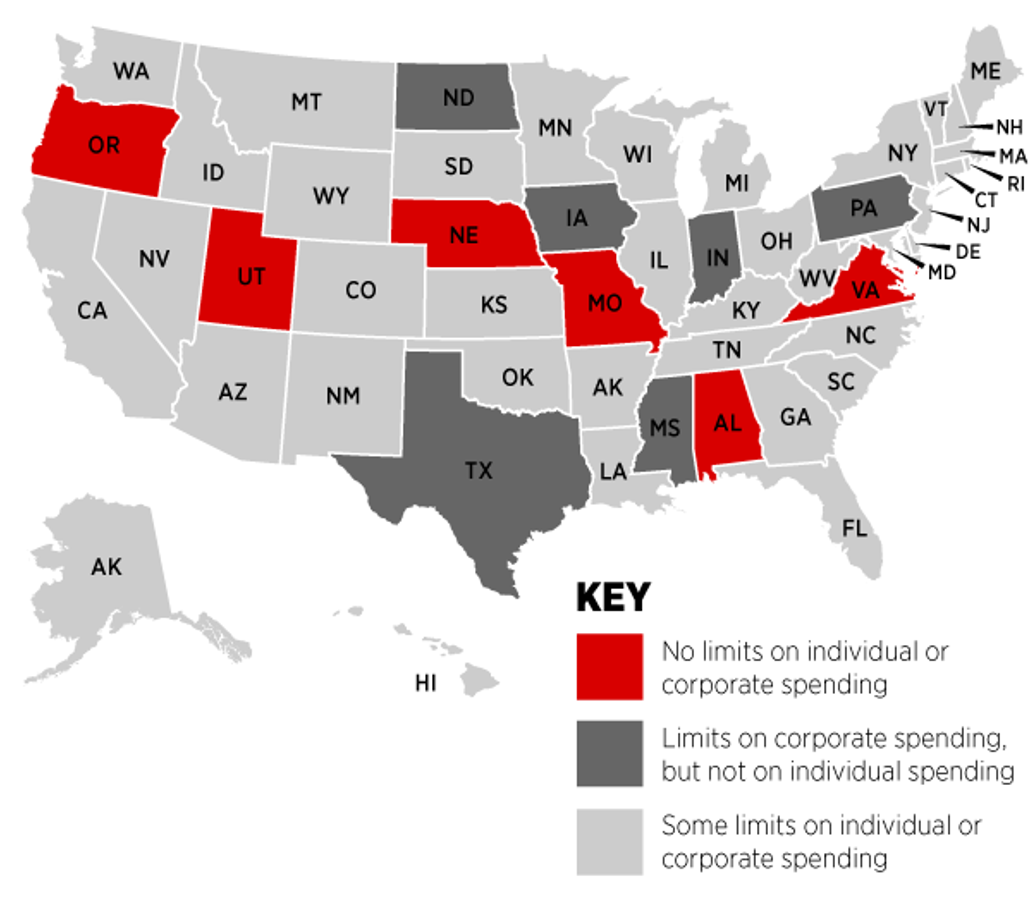

The Show-Me State is the only one in the union with no limits on campaign donations, gifts from lobbyists and the revolving door between elected office and the lobbying industry. Its halls of power, shaped by the deregulatory principles conservatives have long advocated, offer an extreme vision of where our politics could be headed: the complete absence of all restrictions and safeguards on political money. “It’s the O.K. Corral,” says Dave Robertson, a political science professor at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

It’s commonplace for lawmakers to leave office and go directly into a lobbying job. Some legislators have even given up their posts early to cash in — last summer, for instance, the top-ranking state senator quit a year before his term ended to take a lucrative position at a Sinquefield-backed lobbying firm. Industry is so involved with policymaking that lobbyists have occasionally catered official committee meetings. As a result, the line between lawmaker and lobbyist can blur: one state state senator, Ed Emery, recently said that he viewed lobbyists as “unpaid staff.”

And without a limit on gift-giving, lobbyists are free to pay for legislators’ meals at high-end steakhouses, treat them to rock concerts, squire them to WWE wrestling matches and baseball games, the Masters Golf Tournament and the Kentucky Derby. (By contrast, Iowa has a “cup of coffee” rule, barring legislators from accepting any gift valued at more than $3.) At one point, a former state House Speaker, Tim Jones, was known for allegedly accepting so many handouts that the Post-Dispatch editorial board nicknamed him “Timmy Tickets.” (Jones says it was his “practice and habit to severely limit any gifts I accepted” and to reimburse the value of gifts to the giver.)

In the summer of 2007, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned a recent law that erased all limits on campaign giving. Sinquefield, a disciple of free-market economics and small-government gospel, was on his private jet when he heard the news. He soon responded with an announcement of his own. He would create an armada of political action committees, 100 of them in all, and circumvent the law by funneling the millions of dollars he would’ve given directly to candidates through these PACs in smaller, legally permitted chunks. There was nothing in the law to stop him, and the message he sent to the state legislature was clear: I’ll make a mockery of the limits until you repeal them. The next year, the Republican-controlled legislature complied.

A true rags-to-riches tale, Sinquefield (pronounced Sing-field) was given over to a Catholic orphanage in north St. Louis by his widowed single mother before going on to earn degrees from St. Louis University and the University of Chicago. He eventually cofounded a global investment firm that now manages almost $400 billion. And when he grew “bored” of making money in the mid-2000s, he returned to Missouri and embarked on a mission to use his vast wealth (he won’t say how much he’s worth) to transform his home state into a low-tax, small-government utopia.

Consultants now speak of two distinct periods: Before Rex and After Rex. Sinquefield has poured nearly $40 million into campaigns, committees and ballot initiatives, making him easily the state’s largest donor, a figure comparable to North Carolina’s Art Pope. All of his giving, whether to candidates or causes, seeks to advance two issues: Eliminating income taxes at every level of government, and promoting school vouchers and other alternatives to the public education system. He cofounded the Show-Me Institute, which bills itself as the “only think tank in Missouri dedicated to promoting free markets and individual liberty.” Pelopidas, a media company and lobbying firm that counts Sinquefield and his wife as its largest clients, has its own TV and radio studios, a filmmaking division and a digital strategy shop working to spread the anti-tax gospel. According to Tony Messenger of the Post-Dispatch, “he’s a fully integrated vertical of the political system.”

State Sen. David Pearce, a Republican, knows what it’s like to wind up on the wrong side of Sinquefield’s machinations. Pearce is a staunch defender of public schools, and as the chair of the Senate Education Committee, he often drew the ire of Sinquefield and his team. For his troubles, when Pearce last ran for reelection he found himself with a primary challenger flush with $200,000 in Sinquefield money. (Travis Brown, Sinquefield’s adviser, says, “Many interests, including ours, had opposed Senator Pearce due to his opposition to school choice initiatives across Missouri.”) Pearce prevailed but the experience of battling Sinquefield’s largesse has caused him to rethink his 2008 vote to repeal the contribution limits. “I’ve cast 25,000 votes in the legislature,” he tells me, “and that’s probably the worst vote I’ve ever taken.”

Those who support the current system say it works because there’s disclosure — disclosure of donations, disclosure of gifts. Which is somewhat true: While many of Sinquefield’s contributions are made in the light of day, others can be run through nonprofit groups that don’t reveal their funders. (In 2014, Sinquefield routed a $300,000 effort to oust a county judge through a Washington, DC nonprofit.) Lobbyists are required to say how much they spend on concerts and dinners, but a loophole in the law lets them name a committee or the entire Missouri senate next to the expense — sparing guests from public scrutiny.

It’s hard to point to any one indicator as proof of the success or failure of Missouri’s no-limits experiment. But the reputation of Jefferson City, the seat of power in the state, could be seen as emblematic. In my reporting, I heard Jefferson City described as an adult frat house, a cesspool and Sodom and Gomorrah. A longtime lobbyist I met for lunch there described the place like this: “The legislature is like a bunch of people being at a convention. They’re all away from home and there’s free booze all over the place. There are a lot of young kids looking up to them and calling them ‘senator’ and are happy to go have a drink with them. The wife’s not around, you’re away from your social structures and there’s a lot of stupid crazy shit that goes on.”

Schweich was disgusted by what he saw. He recast the auditor’s office to be more law enforcement-oriented. In his first four years in office, he oversaw more than 500 audits, catching more than 30 officials stealing public funds and securing 16 indictments and nine convictions. And while he had his partisan blind spots, Schweich didn’t hesitate to criticize the legislature — run by his own party — or wealthy outside interests. Of course, his active role as a champion for clean government earned him enemies. During his time as auditor, he was sued (unsuccessfully) almost a dozen times by Sinquefield and his underlings. In a speech, Schweich suggested an amendment was even introduced to curb the auditor’s power, and said when he asked a member of the state legislature why it would want to cut back on the authority of Missouri’s taxpayer watchdog, he was told, “Because Rex asked me to.” (Sinquefield’s adviser, Travis Brown, says, “I do not believe that is accurate. I am not aware of what this may refer to.”)

Schweich had a roving mind that never turned off. On long drives to Springfield or Kansas City, he regaled staff members with arcane facts and stories from his days at the U.N. or in Afghanistan. Tyler Holman, the political director on Schweich’s first campaign, told me that he diligently followed current events to keep up with his boss’ long disquisitions on American foreign policy or tax reform or welfare. Schweich was also an amateur rock historian who revered the Rolling Stones. He saw the band live almost every time they toured the States. “Imagine us having these really deep intellectual conversations and debates in the car,” Holman says. “Meanwhile, ‘Brown Sugar’ is blaring in the background.”

The older of two children, Schweich grew up in Clayton, a well-off suburb a few miles west of downtown St. Louis. As a kid, he loved to write and talked about being a lawyer — he once wandered over to a neighbor’s house and asked to borrow an introductory law textbook. Always small for his age, he was recruited to be a coxswain for the Yale rowing team. After graduating from Harvard Law in 1985, Schweich took a job at Bryan Cave, the top law firm in Missouri, and made partner before he was 40.

He worked with former U.S. Senator John Danforth (R-Mo.), a towering figure in Missouri whom he deeply admired, on an investigation into the 1993 siege on the Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas. When Danforth was tapped to be U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Schweich followed him to New York and later held senior-level jobs in the State Department and the George W. Bush administration. “He’d been under all these people all this time, watching and learning,” says Schweich’s friend Martha Fitz, who also happens to be Danforth’s longtime assistant. “I think at some point he said, ‘I want to be the guy.'”

Schweich returned home in 2008, and surprised friends and colleagues with a plan to run for office. Most people had pegged him as the quintessential right-hand man, the chief of staff for life, the faithful deputy. Danforth, his mentor, advised him against it. If anything, the advice backfired. “I think that was a big motivator to Tom,” he says. “He was just determined to run and wanted, I think, to prove me wrong.”

Although Schweich hailed from a more moderate, St. Louis-wing of the GOP, he found that he connected with people all over the state, with Tea Partiers and the Bible Belt crowd, with Romney Republicans in the suburbs and city-dwelling millionaires. And he did it without any attempt at everyman political posturing. One time, he and his deputy, Harry Otto, got behind a pick-up truck en route to a conference in nearby Columbia. Schweich saw something hanging from the truck’s bumper. He squinted his eyes. It looked like a pair of rubber testicles. “He said, ‘Harry, is that what I think it is?'” Otto recalls. “I said, ‘Welcome to central Missouri, Tom.'”

- “If you think of it as a club, [Schweich] never really fit into the club.”

The one place Schweich never felt truly accepted, though, was within his own party. He came to pride himself on the fact that he wasn’t just another pawn of its leaders or controlled by any one donor or industry. “If you think of it as a club,” Holman, the former aide, tells me, “he never really fit into the club.”

During his first campaign for auditor, Schweich had turned to one of his biggest funders, a former ambassador to Belgium named Sam Fox in St. Louis, for a cash infusion during the final stretch of the primary race. Fox replied that he’d be happy to help but thought it would be a bad idea — for Schweich. According to a private note Schweich wrote to himself, Fox told him that if he provided the money “the conservative base will start spreading emails saying that ‘the Jew [him] is supporting the half-Jew [me]’ and it will backfire with the anti-Semitic party base.” (Fox says he doesn’t remember the conversation.)

Schweich’s father and grandfather were both Jewish, and Schweich was briefly raised Jewish, but later he and his wife and two children joined the Episcopalian church. He didn’t broadcast his Jewish heritage but he didn’t hide it either. Inside the front door to his house hung a framed document that had belonged to one of Schweich’s ancestors. Signed by the Archbishop of Trier, in western Germany, it allowed Schweich’s relative to leave the ghetto to sell his products in nearby markets. Schweich kept it as a reminder of what his ancestors had endured. His grandfather had drilled into him: Anytime you see anti-Semitism, stomp it out.

The 2010 conversation with Sam Fox wasn’t the first time he’d been warned about anti-Semitism in the Republican Party. (Missourians have only elected a Jewish candidate to statewide office three times, all of whom were Democrats.) In another personal note, Schweich quotes a Republican member of Congress who told him during his first campaign that “if people think you are Jewish, you will never win the Cape area” — an apparent reference to the evangelical, heavily white region around the city of Cape Girardeau. A former state senator named John Loudon had told him that “my ‘funny sounding name’ will really hurt me in the primary because people will think I am Jewish.” And Ed Martin, a former chief of staff to Republican Gov. Matt Blunt and future chairman of the Missouri GOP, told Schweich early in his campaign that people were asking if he was Jewish. Martin urged him “to emphasize in my literature that the Schweich family is a member of a church — which we are,” Schweich wrote. (Martin says it “does not check out” that he told Schweich people had been asking if Schweich was Jewish. He doesn’t recall talking about Schweich’s campaign literature.)

Any fears about his name or heritage working against him must have receded, at least temporarily, after Schweich defeated his primary challenger Rep. Allen Icet with close to 60 percent of the vote and then ousted the incumbent auditor, Democrat Susan Montee, in November 2010. Schweich became the first successful challenger for a down-ballot statewide office in nearly 40 years. He was widely praised during his first term, and for his reelection, the Democrats didn’t even bother running a candidate against him — the first time since the 1860s that a major party hadn’t put up a candidate for a statewide office.

God, these people are running the show,” Schweich once confided to a friend, “and they weren’t elected to do anything.” He was talking about political consultants, a small well-heeled cadre that he believed had amassed far too much power under Missouri’s no-limits system. Schweich himself had hired and fired almost every major consultant in the state by the time of his reelection. All except one.

Schweich had never heard the name Jeff Roe until he first ran for office in 2010. By then, Roe, currently Ted Cruz’s campaign manager, was already the most feared consultant in the state. A native of rural northern Missouri, Roe got his start in politics on the staff of Congressman Sam Graves (R-Mo.) and quickly became known for his win-at-all-costs tactics: digging through opponents’ trash cans and sending young staffers posing as journalists or volunteers into rival campaign offices to capture damning comments. He cut a TV ad in 2006 that made Graves’ Democratic challenger, a 63-year-old activist named Sara Jo Shettles, out to be a peddler of “smut,” plastering a neon “XXX” over her face, because she previously sold ads for Omni, a science magazine owned by the same parent company as Penthouse. (Shettles says she did handle some contracts that included ads for Penthouse.) After Graves’ 2008 opponent, former Kansas City Mayor Kay Barnes, attended a fundraiser at House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi’s home in San Francisco, Roe produced an ad with images of a flamboyantly dressed black man dancing with two women, which accused Barnes of having “San Francisco-style values.”

- “Political Consultants Who Act More Like Mobsters Than Advisors Are Destroying the Republican Party.”

Schweich and Roe never got along. In a pair of op-eds Schweich drafted in early 2014, which were never published, he outlined their multiple run-ins. The first is titled, “Jeff and Me: Influence and Intimidation in the Missouri Republican Party,” and the second, “Political Consultants Who Act More Like Mobsters Than Advisors Are Destroying the Republican Party.” Together they add up to an indignant condemnation of Roe and the consultant class in Jefferson City.

Back in 2010, Schweich writes, one of his consultants said that Roe considered northwest Missouri his “personal fiefdom” and that Schweich would be smart to hire Roe for his direct mail or “some other small part of my campaign” to open doors in Kansas City. When Schweich refused, his consultant told him to at least “play nice” because “you don’t want to piss Roe off.” (The consultant did not respond to a request for comment.) According to Schweich, that same year, when Joe Passanise, Schweich’s treasurer, supported a candidate opposing a Roe client, Roe told Passanise that he would “gut” and “kill” him. (Roe denies the exchange ever took place: “I never said that.”)

As auditor, Schweich believed he had a platform to speak out against the influence of consultants like Roe. According to Schweich, Republicans had blown $23 million on primary races in 2012. At a Republican Party event in St. Louis in early 2013, he gave a speech in which he mentioned Roe by name and accused consultants of fleecing GOP candidates. Afterward, Schweich writes, he got a call from Roe “in which he heaved insults at me” and “brought up that I had dared mention his name in a speech.” Schweich added, “He felt that a mere politician had no business ever mentioning his name in public. He sounded like the Godfather.” (Roe confirms that he called Schweich after the speech, upset that Schweich had uttered his name. “Look, let’s make a deal to never mention each other’s name,” Roe says he told Schweich. “There’s no reason for it. Consultants aren’t the issue.”)

In December 2013, according to his op-eds, Schweich met with his friend and fundraiser Sam Fox, where he brought up what he called Roe’s “scorched earth tactics.” (Fox says he doesn’t recall this conversation.) When word got back to Roe that Schweich had been talking about him, Roe called one of Schweich’s consultants at the time, James Harris, and went on “a tirade against me.” Harris then texted Passanise to say he’d spoken with Roe.

“Good or bad?” Passanise asked.

Harris replied: “Bad. Jeff called angry. Said he would have to take Tom out.” (Roe denies saying he would “take Tom out.” “I don’t talk like that,” Roe tells me. “Take somebody out? No way.”)

Schweich writes that he confirmed Roe’s language — “take Tom out” — and, rightly or wrongly, took it as a threat. (Neither Harris nor Passanise recall the exchange.) At the end of one of Schweich’s unpublished op-eds, he wrote, “As long as consultants act more like mobsters than advisors, as long as they thrive on internal party conflict, as long as they threaten and berate good public officials and as long as they focus more on making money than winning elections, we will continue to lose the confidence of the public. I urge Republicans to take action against this destructive force in our party.” Schweich never published any of this. But he hadn’t heard the last of Roe.

Every state writes its own rules on campaign spending. Missouri is one of six without contribution limits, and the only state without limits on lobbyist gifts as well.

On the afternoon of October 7, 2014, Nathan Adams, the man Schweich had hired to run his eventual campaign for governor, received a troubling email. “John Hancock called me the other day,” a Schweich donor wrote. “He is definitely helping Catherine Hanaway. Believe he has Tom’s faith incorrect.” When Adams followed up, he was told that Hancock, a veteran Republican operative, was telling people Schweich was Jewish.

Four different Schweich staffers tell me they heard similar versions of the Jewish rumor coming from people in different parts of the state. All of them traced back to Hancock. A major donor in southwest Missouri, David Humphreys, says Hancock made an offhand comment about Schweich being Jewish in a September 2014 meeting. Humphreys says he perceived the comment as anti-Semitic and told his mother afterward, “I just finished a meeting with John Hancock. I am not going to tell you why and I am not going to tell you what he said, but I do not want us giving Hancock any money for any reason.” (Hancock says he doesn’t dispute Humphreys’ account.)

Hancock had kicked around Missouri politics for 30 years and his specialty was opposition research, the art and science of knowing everything you can about a competing candidate. Hancock had even briefly worked for Schweich in 2011, which made the thought of Hancock spreading misinformation about Schweich’s religion all the more confusing. According to Schweich’s aide, Jeff Earl, Schweich wondered, “Why is this being brought up? What do they mean by it?” The only conclusion that made sense to Schweich was that Hancock was heading an anti-Semitic campaign to hurt Schweich’s standing among Missouri’s Christian voters.

Schweich’s staff asked John Danforth to intervene. In November 2014, Danforth called Hancock and asked him about the allegation. Hancock denied then — and denies now — saying anything anti-Semitic or bigoted about Schweich. He said he had believed Schweich was Jewish and wouldn’t make the same mistake again. Hancock tells me, “We talked and I felt, after that conversation, that Danforth believed me that I was not an anti-Semite.” (When I ask Hancock why he presumed Schweich was Jewish, if it was just based on his last name, he replies, “Yeah. I just … just stupid.”)

Moments later, Hancock got a call from Schweich. Hancock, who was about to enter the race for state party chairman, says that Schweich angrily told him not to run. Hancock countered that Schweich didn’t have the temperament to run for governor. But in the end, Hancock says, he insisted to Schweich that he’d stay neutral in the governor’s race if elected chairman. “I said, ‘Tom, my job, if I am the chairman, is to say good things about Republicans, bad things about Democrats, and I’m going to say good things about you.'” It was the last time the two men spoke.

Friends and former aides tell me that Schweich only grew more fixated on Hancock in the months after that conversation. Gregg Keller, a consultant who worked on two Schweich campaigns, tried to explain to me why the rumors consumed Schweich the way they did. “Tom’s greatest strength was his intensity and his focus,” he tells me. “When Tom Schweich decided that he was going to do something or accomplish something, it was simply a matter of time until that thing came to pass. The downside of that was that Tom was so intense and so focused that when he became focused on something, he literally was almost physically incapable of turning his attention elsewhere.”

As Schweich grew more alarmed at Hancock’s comments, he watched his likely opponent in the Republican gubernatorial primary, Catherine Hanaway — also Hancock’s preferred candidate — collect nearly a million dollars from a single source: Rex Sinquefield. In a previously unreported email to Sam Fox, Schweich wrote, “Apparently, he [Sinquefield] is determined to stop any chance of me becoming governor, at any cost. That is because he cannot control me.” (Brown, the Sinquefield adviser, replies: “Statewide candidates win when they convey a compelling vision for their state to voters. Personal attacks on private donors is not a compelling vision.”)

Schweich had met with Sinquefield several times in the past, and had previously accepted a smaller donation from Sinquefield during his first auditor’s campaign. But now he instituted a “No Sinquefield” rule for his gubernatorial campaign, one former aide told me, a bold stance against “King Rex,” who was, Schweich said in his email to Fox, “literally trying to take complete control over state government by any and all means.”

Three weeks after he launched his bid for governor, a radio spot targeting Schweich appeared on Missouri talk radio. A narrator imitating the southern drawl of Frank Underwood, the murderous Democrat from House of Cards, called Schweich “weak” and mocked his appearance: “Just look at him. He could be easily confused for the deputy sheriff of Mayberry” — a reference to the bumbling Barney Fife character from The Andy Griffith Show. The narrator called Schweich a “pawn” of President Obama and Democratic Sen. Claire McCaskill, who wanted him to win the Republican primary because he was “an obviously weaker opponent” against the Democratic candidate, Chris Koster. “Once Schweich obtains the Republican nomination,” the Underwood stand-in said, “we will quickly squash him like the little bug that he is and put our candidate, Chris Koster, in the governor’s mansion.”

Schweich knew he wasn’t leading-man material. He even joked with friends that one of his campaign slogans would be, “I didn’t get here on my looks.” But the Fife spot got under his skin. “The ad really threw Tom into an emotional tailspin at the time,” a former Schweich aide tells me.

The identity of the person who produced the ad, which ran in media markets across the state, was a mystery at first. A front group named Citizens for Fairness in Missouri claimed credit and Hanaway denied any involvement. Only later, after Schweich’s death, was it revealed who actually created it: Jeff Roe.

The ad’s timing was no coincidence. It ran on the eve of the biggest Republican confab of the year, the 2015 Lincoln Days convention in Kansas City, where Schweich would make his first appearance before the party faithful as a candidate for governor. As the humiliating ad made the rounds, and with Schweich already at war inside his campaign over whether to go public about Hancock’s Jewish comments, the weekend’s events only brought more turmoil. Hancock easily won his race for party chairman, while Schweich lost badly to Hanaway in a straw poll. Afterward, Schweich was scooping ice cream for a long line of activists in the hotel lobby. According to two Schweich aides who were present, Roe stood watching Schweich — waiting to see, as one aide put it, “if he was going to break under the pressure.” (Roe tells me he got in line to talk to Schweich at the close of Schweich’s ice-cream social. He says there was nothing at all malicious about his visit. “It was kind of like driving down the street and giving a head nod to someone else driving,” he says. “We talked. We weren’t prowling around. It wasn’t like that at all.”)

The following week, Schweich resolved to go public with his allegations against Hancock — with or without his campaign’s support. He began talking to reporters and put a call into the Anti-Defamation League. But on the last day of his life, February 26th, after he spoke to his close friend Martha Fitz about the supposed anti-Semitic comments, and she again told him to let it go, Schweich knelt down next to his bedroom closet, removed a .22 caliber pistol from his gun safe and shot himself in the head.

Schweich’s closest friends and advisers were stunned. Danforth had spoken to Schweich just two days earlier and sensed no hint of what was to come. “I sure knew Tom very well,” Danforth tells me. “I’ve been around enough time that I’ve known suicidal people. I’ve known suicides. I never ever would’ve dreamt it [with him]. Wired? Yes. Mentally ill? No.”

Fitz was similarly at a loss. “This thing is so layered and complicated because he really did want to stomp out all of this bad stuff, and he was the one guy who I could see who could just sort of somehow do it,” she says. “I’ve seen him so many times do things that you just didn’t think that he would do — and he would do them. He would out-strategize and outthink and outwork everybody and put a good team around himself or try to and never give up.” She adds, “That’s why in my mind I’ve always called it a crime of passion against himself.”

They arrived from all corners of Missouri and beyond, filling the pews at the Church of St. Michael and St. George in Clayton. Statewide officeholders, from Governor Jay Nixon on down, were there. Missouri’s two U.S. senators, Democrat Claire McCaskill and Republican Roy Blunt, had come to pay their respects. Schweich’s old friend and mentor John Danforth approached the pulpit. An ordained Episcopalian priest known to many as “St. Jack,” the 78-year-old wore white robes and a black-and-gold stole as he delivered the eulogy to his former protégé.

Danforth described Schweich as a brilliant and complicated man, and a “model” public servant. In the days after Schweich’s death, Danforth said he’d come to believe that “politics has gone so hideously wrong, and that the death of Tom Schweich is the natural consequence of what politics has become.” Elections always have and always will be combative. But for those who saw no issue with bullying and personal attacks, he said, “Words do hurt. Words can kill. That has been proven right here in our home state.”

The news of Schweich’s death made national headlines. Meet the Press host Chuck Todd called it “a shocking political story” that raised “questions over whether the politics of personal destruction have gone too far.” Kathleen Parker, a columnist for the Washington Post, wrote, “As we consider that America has lost a good man who was aspirational in his politics and inspirational in his private life, we face a question with an implicitly foreboding answer: Why would any decent person want to run for public office?” Friends and rivals, reporters who covered him and state legislators who worked with him, struggled to grasp why a man with Schweich’s brains and ambition would take his own life seemingly without warning.

The tragic fallout was not yet over. A month after Schweich’s death, his spokesman, Spence Jackson, was found dead in his apartment in Jefferson City. A rakish 44-year-old who’d knocked around Missouri politics for years, Jackson had been one of Schweich’s strongest defenders. He’d called a press conference on the church steps after Schweich’s funeral to demand John Hancock’s resignation as state party chairman. But several weeks later, police entered Jackson’s apartment to find his body, a .357 Magnum revolver and a suicide note. “I’m so sorry,” it read. “I just can’t take being unemployed again.”

In April, the Clayton Police Department released its final report on Schweich’s suicide. Police said they found no evidence of a whisper campaign or any proof of anti-Semitism in Schweich’s records. The report instead painted Schweich as a mentally fragile man, and his wife Kathy told police that he had talked about suicide in the past. (Kathy Schweich declined to comment for this story.)

Danforth ended his eulogy with a call to action, a return to civility in Missouri politics. “This will be our memorial to Tom: that politics as it now exists must end, and we will end it.” But not much has changed in the year since. John Hancock still chairs the Missouri Republican Party. Rex Sinquefield is no less influential in the state. Jeff Roe, the consultant, has brought his hardball style to Senator Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign. Catherine Hanaway is still running for governor. (Asked for comment for this story, Hanaway campaign manager Nick Maddux says, “Tom Schweich’s suicide was a tragedy and dragging out sensational details a year later only serves to further harm Tom’s legacy.”)

Any semblance of comity among Missouri’s Republican candidates for governor is ancient history. In November, a political reporter emailed me a link to a newly published story describing how one Republican candidate for governor had been caught calling a fellow candidate a “weasel,” “coward,” and “corrupt.” It was hard to tell which was more dispiriting: the name-calling by Eric Greitens, a Democrat-turned-Republican and former Navy SEAL running for governor, or his opponent John Brunner’s decision to secretly record Greitens and feed it to the media. “Hey,” the reporter wrote, “remember that time when Schweich’s death was going to change the tone of Missouri politics?”

On one of my last days in Missouri, I visit a small gated-community west of St. Louis and ring the doorbell of one of the first condos on the block. The door opens and I’m met by an older man in glasses and a sweater vest over a button-up shirt. I see the resemblance — the ears give it away. “Come on in,” says Julius Schweich, Tom’s father.

He shows me into the kitchen of the home where he lives with his second wife, Barbara. (Julius and Tom’s mother divorced in 2001.) A former Air Force pilot and air-show announcer, Julius still gets around pretty well, and we talk about politics, airplanes, St. Louis and Tom. Julius turned 80 on February 27th of last year, the day after his son died. Barbara had given him a birthday balloon and he’d taped it to a wall in the kitchen, where it now hangs limply, slowly losing air. Julius tells me he won’t take it down until he turns 81, a year and a day after Tom’s death.

He takes me down into the basement, where copies of Schweich’s books rest on the desk near an airplane joystick hooked up to the computer. The shelves are stocked with vintage cameras and model planes. We move to another room with an unfinished wet bar in one corner. A large framed photograph rests on the floor leaning against the wall.

I saw a smaller version of the image — four fighter jets streaking across the sky in formation — in Julius’ office. He’d taken the shot himself, he says, and framed it for his son, who said he would hang it in the governor’s office if he got elected. A quote runs beneath the photo, and Julius’ voice cracks as he tries to read it. “Integrity is one of several paths,” it says. “It distinguishes itself from the others because it is the right path, and the only one upon which you will never get lost.”

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, now known as Type Investigations.