Jude said his body ached, and he was feverish. The 40-year-old was being held with dozens of other Haitians in a crowded U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement facility at the Alexandria International Airport in Louisiana. “They give you Tylenol, ibuprofen, that’s it,” he told The Intercept in late May. “After that, they just want to send you right back to your country. If you die, you die.”

Jude, who is being identified by a pseudonym to protect him and his family, said he’d tested positive for the coronavirus at the nearby Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center, where he’d begged staff to send him to the hospital. But instead of receiving medical treatment, Jude said, he was being deported back to Haiti.

With approximately 120 ICU beds, and even fewer ventilators, for a population of 11 million, the island nation was bracing for the worst. Haiti had already closed its borders and shut down airports in March, after its first two cases of infection were reported, and medical experts warned the pandemic could be catastrophic for the impoverished country’s already debilitated health system. But the morning after he spoke with The Intercept, Jude was fitted with shackles on his wrists and ankles and marched out to a chartered plane waiting on the runway. With him were four other Haitian immigrants who told The Intercept that they had also been quarantined at Pine Prairie after testing positive for the virus. The May 26 deportation flight was one of seven to touch down in the Haitian capital since President Donald Trump declared the pandemic a national emergency on March 13.

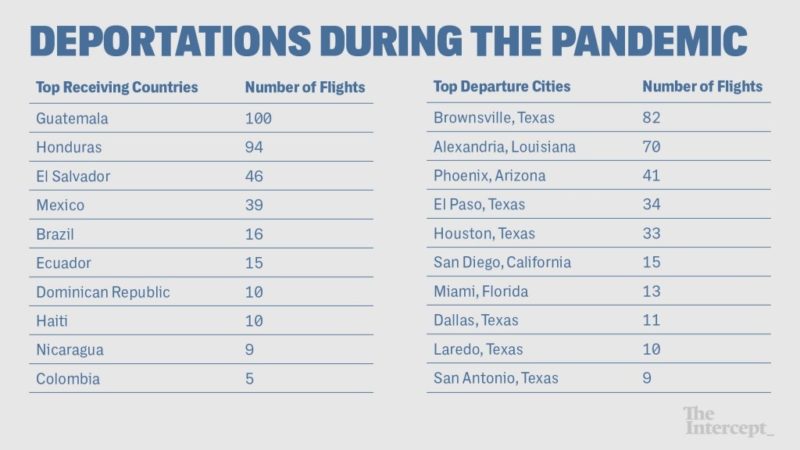

As countries closed their borders and public health guidance urged restrictions on movement to contain the pandemic, the United States likely chartered more than 350 deportation flights to at least 15 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean between February and late June, according to flight data analyzed by the nonprofit Center for Economic and Policy Research. Some of those flights had people on board who tested positive for the coronavirus after landing, according to government officials in the receiving countries. CEPR’s analysis, based on data from the public flight tracker FlightAware, designated flights as likely deportations if they were operated by airlines known to charter with ICE and matched known deportation routes. The true number of deportation flights is probably even greater, according to CEPR.

- Between February 3 and June 24, the Center for Economic and Policy Research identified 351 likely ICE deportation flights to Latin America and the Caribbean. CEPR analyzed data from the public flight tracker FlightAware and designated flights as likely deportations if they were operated by airlines known to charter with ICE and matched known deportation routes. Click on individual airports to see the number of departing and arriving flights. Data visualization: Akil Harris/The Intercept. Source: Center for Economic and Policy Research

New cases of the coronavirus are rapidly rising in most of Latin America. Some government officials complain that instead of helping the region fight the pandemic, the U.S. is only fanning the flames of contagion. Interviews with people detained by ICE and government and public health officials in Haiti and Guatemala make clear the repercussions of hard-line immigration enforcement at any cost. Most imminent are the public health concerns, as the U.S. fails to consistently test for Covid-19 infections among those it plans to deport. Beyond that, reporting in receiving countries reveals that returning migrants have become targets for blame, while limited public health systems struggle to cope with the crisis. Finally, there are growing diplomatic consequences, as the U.S. pushes allied nations to allow the deportation flights to land.

In response, leaders like Haitian Foreign Affairs Minister Claude Joseph have repeatedly pleaded with the U.S. government to suspend the flights. “I have many times over the phone tried to convince our American friends,” Joseph told the Miami Herald. U.S. Congress members and medical organizations have also petitioned the Trump administration to issue a moratorium, with groups like Doctors Without Borders warning that a major outbreak will be “catastrophic” for countries with “fragile health systems.” But while the Trump administration has invoked the pandemic to justify new restrictions on immigration, it has continued to forge ahead with deportations, creating a petri dish for the virus in crowded immigration detention facilities and then exporting it overseas.

Flight Risk

From the early days of the pandemic, the U.S. paid little heed to public health guidance when it came to detained immigrants, and detention centers have become hot spots for the illness. ICE updates its numbers irregularly, but as of June 19, it had tested 8,858 detainees; as of June 25, 2,521 were reported positive for the virus. An epidemiological model, funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, estimated from ICE’s existing data that at least 72 percent of the population in detention could potentially become infected. Yet ICE has continued to detain immigrants, then deport them, and has even recently expanded its flights to include Liberia and India, where health officials confirmed that 22 people had tested positive for Covid-19 after landing on May 19.

Central America’s Northern Triangle, however, has received the majority of flights, since many of the migrants arriving at the U.S.’s southern border in recent years have been from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. Of 351 likely deportation flights between February 3 and June 24, according to CEPR, 240 went to the Northern Triangle. Guatemala was the top recipient with 100 flights.

After dozens of returnees tested positive in March and April, Guatemala refused to accept any more flights until the U.S. agreed to certify that each person had tested negative before departure. After the U.S. agreed, flights resumed in May, but shortly thereafter, another person tested positive after landing in Guatemala City, casting doubt on the reliability of that testing. ICE did not respond to The Intercept’s repeated requests for information on testing, including its testing protocol agreement with Guatemala.

Central America’s Northern Triangle received the majority of the 351 likely ICE deportation flights identified by the Center for Economic and Policy Research between February 3 and June 24. The drought-wracked region is now grappling with a rise in new coronavirus cases.Image: Graphic: Soohee Cho/The Intercept. Source: Center for Economic and Policy Research

The country’s new president, Alejandro Giammattei, a physician and conservative, was notably livid during a May 21 online event hosted by the Atlantic Council. The previous month, Guatemala’s public health ministry had reported that nearly 20 percent of the country’s Covid-19 cases had come from U.S. deportation flights. “Our hospitals have limited capacity, but now we have to treat these patients infected with a disease that didn’t originate here,” he said. “This creates such a burden for us. … Guatemala is an ally of the United States, but I don’t believe the U.S. is an ally to Guatemala, because they don’t treat us like one.”

“They’re capturing migrants in the United States, then putting them in detention where they get infected, and sending them back to us,” said Dr. Lucrecia Hernández Mack, a physician and member of the Guatemalan Congress. “And our hospitals can barely cope from day to day, let alone with the situation we are in now.”

Questionable Assurances

ICE claims that it follows the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines to prevent the spread of Covid-19. Yet while the CDC has emphasized the need for social distancing and warned that any form of travel risks spreading the virus, Jude said he was transferred to multiple detention centers in March and early April, traveling hundreds of miles on crowded buses before testing positive later that month. Even after he tested positive, he said, ICE kept putting him on buses with other detainees rather than isolating him until he recovered.

In March, Jude was shuffled to various facilities in Georgia, including the Irwin County Detention Center, the Folkston ICE Processing Center, and the Stewart Detention Center. From there, Jude said, he was placed on a packed bus with others from Haiti, Guatemala, and Mexico and sent to an ICE staging facility at the Alexandria airport in Louisiana to await deportation.

The Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, GA.Image: Jonathan Wiggs via Getty Images

At the airport, he was held in a room with about 60 other Haitian immigrants. Among them was Stanley, 25, who like other detained or recently deported immigrants cited in this article is being identified by a pseudonym. Stanley told The Intercept that he’d been transferred from the Glades County Detention Center in Florida, where he said several detainees were sick with fevers and having difficulty breathing. Sixty-six detainees at Glades have since tested positive for Covid-19, according to ICE.

On April 7, after nearly a week at the airport, Jude and Stanley said they were preparing to be deported to Port-au-Prince when they were pulled from the flight at the last minute, along with about two dozen other Haitians. At least three individuals who remained on the flight tested positive for Covid-19 after landing in Haiti, according to the country’s Ministry of Public Health. A week after the flight, 13 staff members at the Alexandria facility also tested positive for the virus.

Jude and Stanley were transferred to the nearby Pine Prairie ICE Processing Center, where according to Stanley, they were put in a cell with others who’d been detained with them at the airport. Jude, Stanley, and four of their cellmates told The Intercept that they came down with fevers and body aches soon afterward. One man, 34-year-old Daniel, said he was so sick he couldn’t walk. “I couldn’t even move,” he said. “I had to get wheelchaired to a vehicle and wheelchaired to the hospital.” All six men said they tested positive for the virus at Pine Prairie in April. ICE has reported 30 confirmed cases at the facility.

GEO Group, the private prison company that runs both the Alexandria and Pine Prairie facilities, declined to comment for this article. ICE did not respond to The Intercept’s requests for comment, nor did the Glades County Detention Center.

Henry Lucero, the executive associate director of ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations, told a Senate Judiciary Committee panel in June that due to a lack of testing kits, ICE doesn’t always test people before moving them from one detention facility to another, nor does it test everyone it returns on deportation flights. Lucero said the agency had acquired “2,000 testing kits from the Department of Health and Human Services” and “is slated to receive an additional 2,000 tests per month from HHS for the foreseeable future.” HHS did not respond to repeated requests from The Intercept for information about the shortage of tests.

With limited testing, the agency can’t accurately gauge how extensively the virus has spread among detainees, said Dr. Joseph Shin, co-medical director of the Weill Cornell Center for Human Rights in New York. “It’s like rolling the dice,” he said. “They may not be symptomatic, but you don’t know if they are infected, or that they’re going to be symptomatic and they’re just in an incubation period.” Also problematic is the decision to blindly move detainees multiple times. “It flies in the face of our general principles of social distancing and minimizing the movement of people,” Shin said. “We’ve seen how quickly this virus can leap to individuals in congregate settings, and that includes the staff, and also can follow these people out into the community to seed further infections.”

During his testimony, Lucero conceded that his agency knew some deportees had tested positive after arriving in their home countries on U.S. flights. “We are aware of reports,” he testified. “But there were no known positives that were removed actively with Covid-19.” Before someone boards a flight, agents look for symptoms such as cough or fever, Lucero said, adding that they also randomly test a subset of detainees regardless of their symptoms.

In negotiations with U.S. diplomatic staff, governments like Haiti’s have received additional assurances. “The American government assured the Haitian government that the people who would be deported in the month of May had not been exposed to the virus,” a spokesperson for Haiti’s foreign ministry told The Intercept. The U.S. Embassy in Haiti declined to comment.

Because of the high risk at sites like detention centers, the United Nations has recommended that individuals who test positive for Covid-19 in such facilities be quarantined in isolation from the general population until they have tested negative on two subsequent tests. Jude, Stanley, and Daniel said the medical staff at Pine Prairie initially told them that they would not be removed from quarantine until they had tested negative twice. Stanley said they were tested regularly using a cotton swab inserted deep into their nasal cavities. The tests caused so much pain and discomfort that some of the detainees began to object. “Every 24 hours, they kept coming to pressure us to take the test,” said Stanley. “They just come every day saying, OK, you guys gotta take a test.”

Altogether, Jude said he was tested six times at Pine Prairie. Each time, he was told the results were still positive, he said. But just a day after he received the results of his sixth test, Jude said staff told him to “pack up” because ICE planned to deport him the next morning. He was listed as a passenger on a May 11 flight to Port-au-Prince, according to a flight manifest obtained by The Intercept.

Once again, Jude and Stanley were transported to ICE’s holding facility at the Alexandria airport. “We were shackled up,” said Stanley. “With everybody else, to get ready for the flight.”

But, after public outcry, the two men were pulled from the flight a second time. Prior to their departure, another detainee, Stephane Etienne, had spoken to immigration advocates and the media about his own recent positive test results. He said he knew of others on the flight manifest who had also tested positive.

The men gained only a short reprieve. Two weeks later, Jude, Stanley, and Daniel were all deported. Two other Haitian immigrants who told The Intercept that they had tested positive at Pine Prairie were deported as well. Jude said he was still reporting symptoms of Covid-19 at the time. As the Miami Herald reported, immigrant rights advocates said they knew of eight Haitians deported on May 26 who had previously tested positive. Yet Daniel told The Intercept that there were actually nine of them on the plane — that he knew of — who had been in quarantine after testing positive at Pine Prairie.

When the buses arrived at the airport, Jude and Daniel said they each once again had a swab jabbed up their noses. This time, they were given a “rapid test,” according to interviews and the Miami Herald. As Lucero mentioned during his testimony, ICE had recently bought 10 Covid-19 rapid-testing machines manufactured by Abbott Laboratories, which Trump has touted in press briefings. The Abbott ID NOW test, run on a machine about the size of a toaster, typically produces a result within 15 minutes. The machines are currently being used under an emergency authorization issued by the government, but the test’s accuracy is still being questioned by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. In May, the FDA issued an advisory warning that the rapid test could yield “potential inaccurate results.” The FDA stated that it is working with Abbott to alert the public that “any negative test results that are not consistent with a patient’s clinical signs and symptoms … should be confirmed with another test.”

After testing negative with the rapid test, Jude and Daniel said they were told that they’d been cleared to travel. They were among 30 Haitians ICE deported on May 26. As the Department of Homeland Security later acknowledged, only 16 of these deportees were even given a rapid test for Covid-19 before they were deported.

Stigma Upon Return

Returning migrants not only suffer from the physical effects of the virus but also become targets for blame in their home countries.

At La Aurora International Airport in Guatemala City, where deportation flights land, officials don’t have enough tests to be able to test each returning migrant. Instead they are checked for any visible signs of illness such as fever and cough, said Hernández Mack, who has been monitoring the government’s response to the pandemic. “They take their temperature and give them a quick physical evaluation,” she said.

An immigration official uses a protective face mask as a preventive measure against the new coronavirus, COVID-19, upon the arrival of Guatemalan migrants deported from the United States, at the Air Force base in Guatemala City, on March 12, 2020.Image: Photo by JOHAN ORDONEZ/AFP via Getty Images

Initially, in March, deportees were sent to a cordoned-off wing of the airport, where a few bare mattresses lay on the floor, and there was little access to food or water, according to Hernández Mack and local news reports. The conditions were so dismal that many walked out, taking a bus or hitching rides home, inadvertently infecting relatives and others along the way.

By June 25, Guatemala had 14,819 confirmed cases and 601 deaths, but the real toll is likely much higher, said Hernández Mack, who is also Guatemala’s former minister of public health. Infections are being spurred even higher by Mexico deporting thousands more people over its southern border with Guatemala. “No one is receiving them or evaluating them,” Hernández Mack said. “They don’t get the test, so we don’t know if they are positive, and they are returning to their communities not knowing they are contagious and could infect their families. … We have a very precarious health system, which is starting to collapse.” Doctors and nurses have protested conditions, according to local news reports, demanding more protective gear and equipment, and the director of the nation’s primary hospital treating coronavirus patients recently tested positive.

To address the growing need, Hernández Mack said the government has created a makeshift hospital in an industrial park in Guatemala City where returning migrants with mild symptoms are now quarantined. The more serious cases are sent to a hospital in the city, but as of mid-May, it had already been overwhelmed, she said.

Much of Guatemala is rural and mountainous, with few health services and largely cut off from the nation’s wealthier capital. In some communities, recently deported migrants are being singled out. Since March, Giammattei’s administration has publicized the idea that migrants are bringing Covid-19 with them from the U.S., while at the same time, his administration has failed to create an effective educational campaign about how people can prevent the spread of the virus. Both elements of that approach have helped sow panic and the persecution of returning migrants, Hernández Mack said. “There are communities who have rejected them not knowing whether they are infected or not,” she said. “They don’t let them enter or reunite with their families, because of the stigma.”

Buses carrying migrants have been barred from entering towns, and some returnees have been expelled from their communities because of fear of contagion. In Escuintla, on the southern coast of Guatemala, one family’s home was surrounded by a mob of angry neighbors who demanded that they leave after one of them tested positive for the virus and the family was placed under quarantine, said Renzo Rosal, a political analyst in Guatemala City. “The police arrived and barely saved them,” he said. “People are scared.”

A Cautionary Example

Exporting the virus to the very allies the United States needs to curb immigration to its southern border is fostering resentment as these leaders are forced to beg State Department and Homeland Security officials not to send their citizens back if they are sick.

In Haiti, calls for a ban on flights increased in April, when three Haitians tested positive for Covid-19 after disembarking in the Haitian capital. In an open letter to Haitian President Jovenel Moïse, 14 civil society groups urged his government to negotiate a moratorium suspending all deportations from the U.S. during the pandemic. A committee of leading Haitian doctors and scientists also recommended a moratorium. Guatemala has gone a step further, repeatedly suspending the flights only to lift the moratoriums under pressure from the United States.

Before and during the pandemic, Trump administration officials have threatened that any country that refuses to accept the deportation flights could face consequences, including trade tariffs and hits to visas and humanitarian aid. In late March, a senior DHS official speaking on background told reporters in a teleconference that it was “not an acceptable position to the government of the United States that any country in the world whose citizens illegally entered our country would not take those citizens back under virtually any circumstances.” The official added, “There’s simply no defense of that position, and we feel very, very strongly about that, and we intend to act accordingly if the needs arise in the future.”

For Haiti and others dependent on U.S. foreign aid, Guatemala has served as a cautionary example. The country was the first to demand that the U.S. no longer return deportees who were positive for Covid-19, while neighboring El Salvador and Honduras have allowed the deportations to continue and been largely compliant. In April, Guatemala was conspicuously absent from any mention as Trump praised Honduras and El Salvador for their help in curbing migration, saying that the U.S. would be sending both countries desperately needed ventilators. Guatemala didn’t fail to notice the slight. “We’ve seen how they’ve assisted other countries with ventilators,” Giammattei said during his Atlantic Council appearance. “We don’t feel very grateful for the way we have been treated.”

At least one U.S. official denied that Guatemala was suffering reprisals for being the first to publicly protest the flights. State Department official Michael Kozak said during a teleconference call that there wasn’t any “hard linkage” between cooperation on removals and ventilators. “It’s not that we haven’t had a cooperative relationship with them,” he said of Guatemala. “It’s just they’ve run into some snags and we’re working through that with them.”

But the perception from within the country is otherwise, said a retired Guatemalan diplomat, who asked to remain anonymous because he’s not authorized to speak for the current government. “It is my understanding that we are being punished,” he said. “The administration has already said it would withhold visas for Guatemalan citizens, including businesspeople and government officials, so it’s a serious challenge for a country like Guatemala that is close to the U.S., and it’s a threat that is taken seriously.”

“Anything Else Is Irrelevant”

Since Jude was deported, cases in Haiti have more than quadrupled, from less than 1,100 in late May to more than 5,400. A Haitian civil servant involved in the country’s Covid-19 response efforts, who did not wish to be identified because he fears reprisals, told The Intercept that he fears that “we’re sitting on a ticking time bomb.” The pandemic is hitting at the same time as a deepening political and economic crisis, and the head of the Pan American Health Organization recently warned that “there is real danger of a large-scale outbreak followed by a humanitarian crisis in Haiti.”

Deportations from the U.S. are exacerbating these issues. Honduras, which has received the second-highest number of flights after Guatemala, has confirmed more than 14,500 cases and 417 deaths, while in El Salvador, at least 5,300 cases and 126 deaths have been reported. Several likely deportation flights from the U.S. have also touched down in some of the hardest-hit countries, including Brazil, now second in the world for infections; Ecuador, which has one of the highest fatality rates in Latin America; and the Dominican Republic, which has more Covid-19 infections than any other Caribbean country.

The situation is also dire in Guatemala, where infections outpace neighboring El Salvador and Honduras. Paulina Lopes, a Mayan community health organizer in the city of Santa Cruz del Quiche in the western highlands, said many in Indigenous Mayan communities are not reporting to the authorities when they’re sick. Lopes said that she’s also heard that some who are critically ill are dying at home because they fear having their community cordoned off by the military if an outbreak is reported. In much of rural Guatemala, hospitals are more like ill-equipped health centers, Lopes said, and “don’t have the equipment or capacity to receive people. Even when there’s no pandemic, they still don’t treat people.”

A strict lockdown enforced by the military and police in Indigenous communities has also increased hunger and malnutrition, already a problem in the long-suffering region wracked by drought and climate change. “They have locked us up in our homes, and there is no work,” said Lopes. “People can’t go to their land to collect or cultivate their food.” Since the lockdown began in mid-March, families suffering from hunger have descended from the mountains, waving white flags to signify that they are starving. They now line the streets of towns and the sides of highways asking for help. “I have never seen something like this in my life,” Lopes said. “Every day it is very tense, very difficult.”

Families can’t afford food, let alone face masks or hand sanitizer, she said. “It is a total lie that the government is helping the rural areas. They say they’ve sent supplies, but it’s a lie. The help hasn’t arrived in our communities.”

Guatemala was already reeling after Trump cut foreign aid to the country in 2019, because he claimed that it wasn’t doing enough to prevent migration to the United States. The rate of malnutrition in Indigenous communities is close to 65 percent. Programs run by Mercy Corps, Save the Children, and other nonprofits that provided food assistance were discontinued due to lack of funding. A longtime U.S. congressional staffer who specializes in Latin American policy, who asked not to be named since he fears reprisal, said that aid to the Northern Triangle had been provided in a bipartisan manner for decades until the Trump administration ended it. Cutting foreign aid was an “incredibly counterproductive move, because this funding was addressing the root causes of migration,” he said. “And stopping people from making the dangerous trek in the first place.”

It would be difficult to find many in the State Department, he said, who thought cutting the funding was good policy. “I mean, this is coming directly from the top,” he said. “This was, you know, a typical tweet by Trump and then the State Department has to go into full gear and figure out what to do next.”

Even when Trump announced in October that he would restore some funding, the congressional aide said, much of it was to be earmarked for law enforcement rather than development and food security. “They would argue that the security funding is needed to stem the migration, but I think that’s ludicrous,” he said. “I mean it’s one piece of the puzzle, but if you don’t have a food secure western highland region in Guatemala and people are starving, then they’re going to migrate. You need both pieces.”

But migration trumps everything in this administration, he said, including growing concerns about leaders in the region exploiting the pandemic to consolidate power. The Trump administration has stood by without protest while “President Bukele is becoming increasingly authoritarian,” he said of El Salvador’s new president, Nayib Bukele, who has given the police broad authority to use deadly force and arrest anyone violating quarantine. Bukele also ordered hundreds of prisoners stripped to their underwear and packed tightly together in a prison patio as a show of force against gang leaders. The U.S. administration didn’t speak up either, he said, when Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who is being investigated for drug trafficking by the U.S. Justice Department, ended his country’s anti-corruption commission in January. And it remained silent last September when Guatemala dissolved its own U.N.-backed anti-corruption commission.

“The only thing this administration cares about is, Are they taking our deportees? And will they work with us in enforcing draconian immigration policies? Anything else is irrelevant,” he said.

Everything the administration is doing now, from cutting aid to deporting people infected with the coronavirus and paying no heed to growing corruption, will only further destabilize the region. “You might not see it today because of the pandemic or because of current immigration policies,” he said. But abandoning Central America will have long-term consequences. “There will be more children, more families who are going to take the dangerous journey north.”

Rosal, the political commentator from Guatemala City, said that ultimately his country, like so many others, believes that it has little choice but to acquiesce to the demands of its more powerful benefactor to the north. “We can neither afford to accept the flights nor reject them,” he said. “Either way, we lose.”

Research assistance by Akil Harris.

Melissa del Bosque is a former Lannan reporting fellow with Type Investigations.

Isabel Macdonald is a freelance journalist and media scholar.