The economic cataclysm brought on by the coronavirus caught American consumers in an extremely precarious position — one that was evident well before more than 50 million people filed for unemployment. By the end of last year, Americans had racked up nearly $4.2 trillion in consumer debt, not including mortgage debt — a record high. The greatest contributor to this surge was not credit card spending or student debt or auto loans, but something newer and, for many borrowers, even riskier: high-interest personal loans, increasingly offered by online financial technology companies known as “fintechs.”

These fintech firms have eclipsed banks and other traditional credit suppliers to become the nation’s No. 1 source of personal loans — the kind of loans people take out when they need extra cash to stay afloat, or when they have already amassed large amounts of debt and are looking to refinance. At the end of 2019, an unprecedented 20.8 million Americans owed money on at least one personal loan — more than one-third of which came from a fintech company.

This surge in fintech lending may have dire consequences for American consumers. Just as financial engineering by Wall Street banks fueled unsustainable consumer borrowing in the 2000s, online fintech companies’ quest to squeeze more debt out of borrowers through loans signed via a few clicks on screens has helped set the stage for a new consumer financial crisis today, an investigation by The Intercept and Type Investigations reveals.

Such borrowing might provide short-term relief to some Americans. And, in light of the current crisis, some fintech firms are working with borrowers to defer payments temporarily. But ultimately, the surge of fintech lending in recent years will likely result in a massive wave of loan defaults over the coming months, as borrowers burn through enhanced unemployment benefits, which have been reduced since the end of July, and the stimulus payments that the federal government began sending out in April. The resulting spike in defaults will be catastrophic for consumer credit.

“The significant GDP decline and unemployment spike in 2020 will pressure borrowers’ income levels and ability to make loan payments,” analysts at Fitch Ratings warned in May. Online fintech loans may be the first to go unpaid, as consumers prioritize keeping up with payments on their most essential possessions, such as homes and cars.

Moreover, Trump administration banking officials have begun to deregulate the industry. Those rule changes are poised to vault already aggressive lending into overdrive, capitalizing on desperation.

In late May, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which regulates federally chartered banks, finalized a rule that would supercharge the online lending industry by bowling over the state interest rate limits that currently protect consumers. In June, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation finalized an equivalent rule that would cover the state-chartered financial institutions that currently dominate the online lending industry.

The attorneys general of California, New York, and Illinois have sued the OCC, contending that its rule violates federal banking law and other statutes, “and would facilitate predatory lending.” If those rules stand, borrowers in many states will face even higher interest rates than they do today, with state regulators powerless to stop them. A second lawsuit targets the FDIC rule.

The OCC is now taking comments on a separate proposed rule that declares a national bank the “true lender” in any partnership, further adding to fintechs’ ability to sidestep state banking regulations.

The mass unemployment brought on by the coronavirus, which has heightened uncertainty about who will be able to pay the loans back, has made investors who fund these loans skittish about pouring more money into the fintech industry, analysts say.

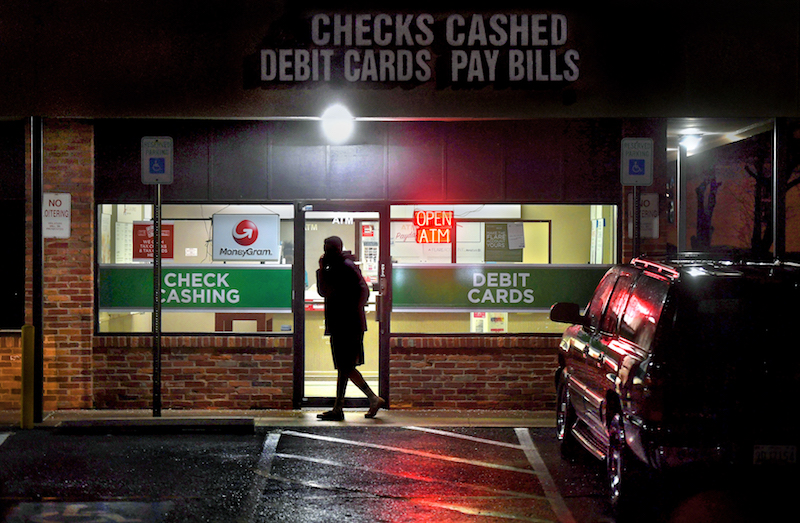

A payday loan store in Gaithersburg, Maryland.Image: Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post via Getty Images

But once the pandemic eases and the economy improves, the new rules mean that the fintech industry — particularly the companies with the largest cash reserves, which are best positioned to weather the current crisis — will be poised for a major comeback. Even now, companies with cash reserves are pressing ahead with new loans, using invasive technologies to scrutinize borrowers’ bank accounts and other assets.

Many fintech companies offer loans in four and five figures while charging interest rates that can range up to 25 percent, 30 percent, or more per year — at a time when the cost of funds to bankers remains at near-historic lows. Some fintechs charge annual interest rates between 160 and 299 percent, in payday lender territory. But the fintech industry is operating at a scale that rivals the storefront payday lending industry.

Their expansion has been driven by firms that position themselves as consumer-friendlier alternatives, with names such as Best Egg, Prosper Marketplace, LendingClub, Avant, SoFi, and Upstart, which lend larger sums of money: often $15,000 or more, to be paid back over three or five years.

These companies are backed by pools of investors that include funds managed by George Soros’s wealth management fund and Goldman Sachs.

Fintechs market themselves as helping struggling Americans by offering cash more quickly than banks or other traditional institutions. And, indeed, for some people, these loans can be a godsend: providing them a financial cushion that allows them to ultimately dig themselves out of debt. Personal finance blogs and online chat boards teem with fintech loan success stories and advice for those struggling to bring their debt balances down and their credit scores up.

On the whole, however, the high-interest loans offered by fintech companies leave borrowers even worse off than before: drowning in an ever-rising sea of debt, with sizable numbers of borrowers unable to keep up with bills. Researchers have found that even before the coronavirus crisis, fintech borrowers were prone to fall behind on their debt payments.

So far, fintech companies have been constrained in many parts of the country by state interest rate limits that protect consumers from excessively costly loans. While fintechs are typically new to the banking industry, seeking fertile ground for profitable business disruption, they rely on old-school, state-chartered bank partners to actually issue the loans.

With the Trump administration mobilizing to deregulate those banks, however, borrowers will be at increased risk.

Members of both the Obama and Trump administrations have also pushed for a federal fintech charter that would allow fintech companies to sidestep state regulators, on the premise that it would help improve consumers’ access to credit. Raj Date, a Prosper Marketplace board member and the founding deputy director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, sees fintech loans as “streamlining distribution into people’s lives” — a convenience for consumers in the era of Uber and Airbnb. “It’s about making the look and feel in financial services as easy as every other thing in your life,” he said in an interview.

In their quest to sign up new borrowers, however, fintechs are pushing the limits of what consumers can actually pay back. The parallels to predatory subprime mortgage lending are too close to ignore, said Diane Standaert, director of the Hope Policy Institute, a consumer advocacy group, and former executive vice president of the Center for Responsible Lending: “It’s like we’re repeating history.”

Preying on Desperate Borrowers

Finding customers whose finances have already spun out of control is a key to the fintech business model. Fintech companies decide what interest rates to charge by analyzing the risk profiles of prospective borrowers. Some base their calculations largely on a borrower’s FICO score. Others use custom algorithms. The higher the risk, the higher the interest rate.

“Part and parcel of the thinking [was] the customer we wanted to serve,” said Jeffrey Meiler, the founder and CEO of Best Egg, on a podcast for fintech investors. “When we really analyzed who we were going to be working with, who we were going to be helping here, it was typically a consumer who is 46 years old, is an individual that has liabilities that exceed assets, and they’re carrying typically $15,000-plus in credit card debt. And they’re looking to make a change.”

In Cleveland, Ohio, Kenneth Gibson fit that description. In the mid-2000s, he opened a restaurant and nightclub down the road from a strip mall in Cleveland Heights. Business was good. But in the winter of 2014, the movie theater in the strip mall closed, along with the nearby Walmart, leaving the area largely desolate during a rough winter. Business at the nightclub fell precipitously, Gibson recalled.

Gibson, now 63, was determined to keep the business going. He ran up tabs on multiple credit cards. But the business still wasn’t making enough money for him to pay back the debts that were piling up or to carry out the renovations he wanted to make on a new location in nearby Shaker Heights. He needed another source of funds.

In the summer of 2016, Gibson’s son suggested that he try getting a loan from Best Egg. It was simple for Gibson to apply online. Initially, he said, Best Egg turned him down. An agent got back to him a few weeks later, however, to discuss some adjustments to Gibson’s application, Gibson said. Once the updated application went through, $17,576.85 appeared in his bank account: the result of an $18,500 loan, minus a 5 percent cut for the lender.

That lender, the loan papers spelled out, was not Best Egg, nor its Delaware-based parent company Marlette Funding. The money actually came from a New Jersey financial institution called Cross River Bank. That meant Gibson’s loan would be subject to New Jersey’s interest rate, not Ohio’s.

Not that Gibson was paying attention to the details. “I don’t even know the amount they gave me,” he said. “I was scrambling. That wasn’t enough to do what I needed to do, so I got other loans, from credit cards or something, to upgrade the business.”

The annual interest rate on Gibson’s loan from Best Egg was a steep 27.25 percent, which vastly exceeded Ohio’s 8 percent annual interest rate limit. With broad exceptions, including payday lending, charging higher interest is barred as usury. But Best Egg and other fintech companies leapfrog over state interest rate caps via a legal springboard that allows lenders from elsewhere in the country to rely on their home state laws — and New Jersey allows interest of up to 30 percent for consumers.

Other online lenders charge even more to some borrowers by piggybacking on Utah banks with a special charter that licenses them to charge interest without any maximum at all. Utah’s WebBank supplies loans for Prosper, Avant, and other mainstream fintech lenders.

According to the terms of his loan, Gibson was required to make monthly payments of $567.67 for 60 months. For five months, he managed to stay current on his payments.

Ultimately, though, the loan from Best Egg didn’t provide a path to financial security. Instead, it dragged him even deeper into distress as his business and health took a turn for the worse.

Marlette Funding and Cross River Bank did not respond to questions about Gibson’s loan.

Gibson is in good company. Even before the pandemic, as much as $1 in every $10 borrowed from Best Egg could ultimately go unpaid, analysts at Kroll Bond Rating Agency estimated. And Best Egg performed better than peers like Avant, which as of early this year was projected to see as much as $1 in every $5 in certain pools go south.

In mid-July, KBRA, the leading ratings agency for the online personal loan industry, announced ratings watches with the potential for future downgrading on $5.6 billion in securities, noting that “uncertainties remain as to how borrowers will perform after the extra $600 weekly unemployment benefit expires at the end of July, other consumer debt products exit their deferral periods, and if the unemployment rate will remain elevated or increase due to continued economic pressure caused by efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19.”

In mid-June, KBRA found that about 10 percent of Best Egg borrowers had asked for payment extensions and another 6 percent in some loan pools were at least a month behind on their payments despite government coronavirus financial aid programs.

And in their August 2020 report on a Best Egg loan pool, KBRA’s analysts acknowledged that high-interest, high-risk loans in the mix could be perceived as “predatory lending” and lead to a backlash.

“These customers may have low income, limited financial means and a negative or limited credit history,” says a section headed “Perception of the Subprime Lending Market.” “Based on one’s view of this sector, it may be interpreted that these lenders are providing credit to an underserved demographic or conversely that they are engaging in predatory lending. This perception could cause lenders and capital providers to exit this market in an economic downturn or if social acceptance is negative.”

A decade after the financial crisis, overleveraged Americans once again stand to lose all that they have.

“Like a fool, I borrowed all that money and just couldn’t catch up,” Gibson said.

The Hamster Wheel

For most lending institutions, having so many borrowers default on their loans would be unsustainable. Indeed, in 2017, investors including George Soros supplied a financial lifeline of up to $5 billion to Prosper Marketplace, after a surge of borrower defaults and balking investors had the fintech firm facing a threat to its survival. Still, Prosper continues to operate in the red: It lost $39.9 million in 2018, despite issuing $2.8 billion in loans that year, and another $13.7 million in 2019.

But, at least before the pandemic struck, investors continued to buy the securities packed with fintech loans, based on analyst projections that the high interest paid will more than offset the hefty share of risky loans that borrowers will be unable to pay off.

Early this year, KBRA reported that privately held Marlette, owner of Best Egg, is profitable.

The need to turn a profit puts pressure on fintech companies to issue even more loans, in order to generate more revenue from interest and fees for issuing the debt. (Borrowers often pay 5 percent or more on top of the principal and interest just to close the deal.) Last year, Best Egg lowered the minimum credit score that it required borrowers to have — from 640 to 620 — deeper into subprime territory, widening its potential customer pool but also opening itself to borrowers who may have an even harder time repaying their loans.

Todd H. Baker, a former banker and now senior fellow at the Richard Paul Richman Center for Business, Law, and Public Policy at Columbia Business and Law Schools, calls the online lending business dynamic “the hamster wheel.”

“They don’t make any money unless they sell the next loan,” he said. “That leads to enormous incentives to do things that you shouldn’t.”

To keep the cash flowing in once borrowers stop paying, fintech investors sell off bad loans to other investors who specialize in collecting whatever they can. And so it was that a Minnesota company called Absolute Resolutions Investments purchased Kenneth Gibson’s loan in June 2017, along with a heap of other rotten Best Egg debts.

IRS, SEC, and New York State records show a fund affiliated with George Soros’s investment management firm has been an investor in Best Egg loans as well as Prosper Marketplace. One of the 11 investment funds that offloaded the pool of Best Egg loans to Absolute Resolutions was QPB Holdings LTD, which is tied to Soros Fund Management and the Fund for Policy Reform, a financial engine behind Soros’s global projects advocating for human rights, democracy, and progressive politics.

Having purchased the rights to the loans from the Soros funds and other investors, Absolute Resolutions sued Gibson in Cuyahoga County court in early 2018, seeking more than $20,000 once interest and penalties were piled on — more than Gibson had borrowed in the first place.

Soros Fund Management has since established a policy precluding investments in products that do not provide a path to financial resilience.

Gibson had no way to pay that money back. The Cleveland Heights City Council declared his nightclub a nuisance in 2016, after police were repeatedly called to the parking lot to respond to disturbances. That was the end for the business.

Unable to repay the loan, and with their finances hurting even more following a medical crisis, Gibson and his wife declared bankruptcy in October 2018.

Yet Best Egg keeps on rolling. As platforms that simply serve as intermediaries between borrowers, banks, and investors, fintechs aren’t set back by borrowers’ failure to pay — as long as someone keeps buying blocks of the securities. Last year, Marlette packaged $1.3 billion worth of consumer loans for sale.

“They may be able to make the loan work for the company, even if [borrowers] ultimately default,” said Lauren Saunders, associate director at the National Consumer Law Center.

A Recipe for Consumer Suffering

In Washington, fintech fanaticism has been a bipartisan affair. It was a banking regulator appointed by Barack Obama, Thomas Curry, who in the final weeks of that administration moved to allow the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to charter fintech institutions, authorizing them to issue loans without partnering with traditional state-based banks. A federal fintech charter — a license for banks to do business under the oversight of federal regulators — would allow the companies to sidestep state regulators and state interest rate caps.

If fintechs have assurances they can charge higher interest rates, without concern that state regulators or courts might clamp down, the industry and its supporters contend, many consumers who previously couldn’t qualify for a loan would be able to get one.

In a speech at Georgetown University in December 2016, Curry raved about how fintechs had “great potential to expand financial inclusion, reach unbanked and underserved populations, make products and services safer and more efficient, and accelerate their delivery.”

A fintech charter also could help address a problem that has dogged online lenders since 2015: a federal appeals court decision that found that only the bank originating a loan could use its home state’s higher permitted interest rate in a state with lower caps, and could not transfer that rate to another company, such as a debt collection agency. That not only deterred lenders from making high-interest loans in New York, Connecticut, and Vermont but raised the possibility of the products getting blocked in other states too. A federal charter would allow fintechs to charge essentially whatever interest rates they wanted, anywhere in the country.

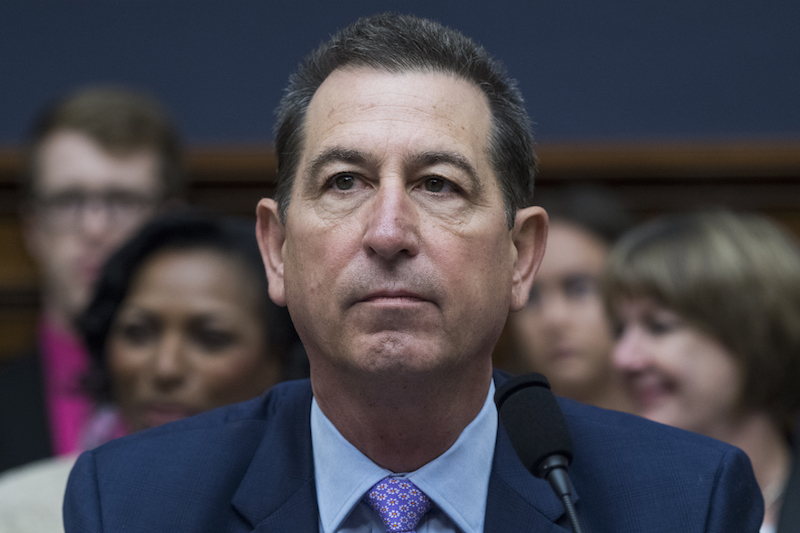

Donald Trump’s appointee as comptroller, Joseph Otting, took up the crusade to create a federal fintech charter and put out a call for applications in the summer of 2018. Otting had served as CEO of OneWest Bank while Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin was the bank’s chair, and there presided over aggressive foreclosures of mortgages relying on robosigned documents.

Joseph Otting, then-Comptroller of the Currency, during a 2018 House Financial Services Committee hearing. Image: Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call

Otting resigned from the post in May 2020, handing the reins to another OneWest colleague, Brian Brooks, who in a statement upon taking office as acting comptroller made clear his intentions to carry on Otting’s work to deregulate fintech.

Dozens of firms expressed interest in a federal fintech charter. Speaking at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University in March 2019, Otting said his office was in talks with “25 to 50 entities” that “feel because they operate across multiple states that having a national banking charter is critical to their business plan.”

Earlier that day, his calendar shows, he made an appearance at the annual meeting of the Marketplace Lending Association, a trade group that represents fintech companies. He had already met with the Online Lenders Alliance, an association representing fintech firms specializing in high-interest loans — just as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau was readying to roll back regulations requiring payday lenders to ensure that their borrowers have the ability to repay their loans. That change took effect in July.

Otting’s quest for a fintech charter suffered a setback in October, however, when a Manhattan federal court ruled against the Trump administration in a lawsuit filed by a state banking regulator. Judge Victor Marrero had found that the comptroller has the power only to license financial institutions that take customer deposits — a definition Congress set long ago with the National Bank Act. Because fintechs lend money that does not come from customer deposits, they don’t fall under the comptroller’s purview, Marrero ruled. In December, the Trump administration appealed the decision to the Second Circuit.

The lawsuit that led to Marrero’s ruling was filed by Maria Vullo, who until last year was superintendent of the New York State Department of Financial Services, which oversees hundreds of state-chartered financial institutions.

In an interview in her office a short stroll from Wall Street during her last weeks on the job, Vullo said she didn’t see an alternative to challenging the fintech industry’s push for a national charter.

“Combined with that attack really on the state regulatory system was the great concern of consumer groups with respect to payday lending and predatory practices,” she said. “Knowing what happened during the financial crisis.”

While serving as deputy attorney general of economic justice in 2010, when now-Gov. Andrew Cuomo served as New York state attorney general, Vullo had seen firsthand the wreckage left by Wall Street banks. A federal fintech charter, she had warned Curry in a January 2017 letter, would “imperil crucially important state-based consumer protection laws,” “create institutions that are too big to fail,” and “increase the risks presented by nonbank entities.”

Vullo remained concerned, even though Congress took steps to prevent a recurrence of the crisis driven by consumer debt and speculative investment. One provision of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act requires banks that partner with investors on securitizations, including those associated with fintechs, to hold at least 5 percent of the product on their own books, aiming to discourage excessive risk-taking.

However, given the fintech industry’s complex web of online lending platforms, banks, securities pools, and investors, Vullo still sees no substitute for direct oversight by regulators.

“A lot of these nondepository institutions just have investors that are backing them, and I don’t know whether their credit decisions and their underwriting decisions and everything else are valid,” Vullo said. “They’re often selling these things in buckets and securitizing them — and, well, we’ve seen that before.”

And, as was the case during the financial crisis, if these lending institutions run into trouble, it’s consumers who stand to suffer most.

“These companies could be fly-by-night companies that then don’t survive, go away, and they’ve already sold the loans to people who are left holding them,” Vullo said. “And they are going after consumers for repayment of the loan, and there’s nobody to go to.”

Evading Usury Laws

The fintech industry has worked hard to stymie regulation at both the state and federal level. In 2017, Vullo and Governor Cuomo asked the state legislature for the power to license and supervise fintech companies doing business in the state, and to place companies issuing consumer loans under $25,000 under the oversight of the Department of Financial Services.

In response, the fintech industry mobilized. State Assemblymember Phillip Goldfeder, a Democrat from Queens and former operative for New York Sen. Chuck Schumer, declined to seek reelection in 2016. Instead, he returned to a job he’d performed even while serving as a New York state lawmaker, according to his financial disclosures: heading government affairs for Cross River Bank, a major player in issuing online loans.

Though Goldfeder waited out the 2017 legislative session before officially signing on with the company as a lobbyist, his 26-year-old chief of staff joined Cross River in late 2016 while the assemblymember was still serving in Albany and is listed on early 2017 lobbying filings as a Cross River contact.

In 2017, Cross River also spent $65,769 on a lobbyist from Mercury Public Affairs who previously worked for Cuomo when he was U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development, and the Marketplace Lending Association paid another lobbying firm $30,000, according to records from New York’s Joint Commission on Public Ethics.

Cross River Bank did not respond to a request for comment.

Vullo’s measure ended up going nowhere. The bill that Cuomo eventually signed at the end of 2017 merely called for the creation of a task force to examine the issue of online lending. That task force never formed. And despite a sea-change election in 2018 that put Democrats fully in charge in Albany, no online consumer lending bill has emerged from the state legislature.

Vullo is now a consultant advising firms on financial regulation and is “regulator in residence” at a financial innovation think tank affiliated with the Partnership for New York City business group.

Lobbyists for the fintech industry also went to work at the federal level, pushing a bill that, despite the 2015 federal court opinion, would free fintech companies to lend in any state, at whatever interest rate borrowers will accept, and pass on bad loans to debt scavengers for collection.

That was also a reaction to efforts like those in New York and other states to place limits on the activities of fintech companies. In 2017, Colorado’s administrator of the state credit code sued Marlette and another fintech lender, Avant, arguing that these companies — not their respective partners Cross River and WebBank — were the actual lenders of record. That determination would make Best Egg and Avant loans subject to Colorado’s restrictions on the interest rates, finance charges, and late fees that can be charged to borrowers. Colorado law limits interest to as low as 15 percent, depending on the size of the loan.

In June, a state court judge sided with Colorado and against Marlette, finding that banks can’t hand other states’ interest rates to their business partners. Under a settlement reached in August, Marlette and Cross River agreed to terms increasing consumer protections, including a process for fielding complaints.

Cross River Bank spent more than $450,000 lobbying Congress and federal regulators between 2016 and 2018, while the deregulation bill was brewing in the House, according to federal lobbying disclosures. In addition, the Marketplace Lending Association spent more than $250,000 on lobbyists, including former congressional staffers from both sides of the aisle.

That action had bipartisan support. Democratic Rep. Gregory Meeks of New York, a longtime friend of the banking industry, co-sponsored with Republican Rep. Patrick McHenry of North Carolina. And progressive Democratic Rep. Maxine Waters, now chair of the House Financial Services Committee, introduced an amendment in committee that would allow the fintech state interest rate shell game to continue so long as rates go no higher than 36 percent — an interest rate that would violate the law in New York, Connecticut, Minnesota, and other states.

After Democrats regained control of the House in 2019, Trump’s banking regulators again jumped into action. In November, the OCC and FDIC proposed rules that together would allow debt agencies to collect on fintech loans even when the original bank’s interest rate is higher than that permitted in the borrower’s state. Two dozen state attorneys general declared their opposition to the FDIC version of the rule, including the three who in July sued the Office of the Comptroller.

“The FDIC simply lacks authority to undertake the Proposed Rule,” wrote Georgetown University law professor Adam Levitin, an expert on the regulation of consumer credit — calling it bad policy as well as illegal, “contrary to the FDIC’s duties to ensure the safety and soundness of State Banks and consumer protection from predatory lending.”

Levitin added in his comment on the proposed rule: “[B]anks’ involvement in the loans is just window dressing for the purpose of evading usury laws.”

The National Consumer Law Center, Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund, the NAACP, Public Citizen, and other groups concurred regarding the OCC version of the rule, warning of a door opening to wider predatory lending. “The OCC’s proposal plays right into the hands of high-cost lenders and their unceasing efforts to evade interest rate and other consumer protection laws,” the groups said in a joint comment.

Noting that the median state interest rate cap on a five-year, $10,000 loan is 25 percent APR, they added: “Efforts to evade state usury caps are inappropriate even if the rates do not reach the triple digits.”

No Protection

Even now, though, Americans who take out loans through fintech companies have few legal protections. Loan terms generally prohibit borrowers from taking court action against a fintech lender directly. Where there’s a dispute, loan agreements typically require borrowers to turn to arbitration proceedings.

Consumer attorneys have begun to sue the debt collectors that pick up the shards failed online loans leave behind.

In California, for example, lawyers are suing Velocity Investments in federal court on behalf of multiple clients, all Prosper Marketplace borrowers. They allege that Prosper violated California law, which requires two witnesses or a notary to grant power of attorney, when it issued the loan, and that Velocity’s attempts to collect those debts were therefore invalid. (The law firm working on behalf of Velocity Investments claims that Utah law applies; before May 2016, Utah did not have any witness or notary requirements for signing over power of attorney.)

Bankruptcy lawyers who try to pin down lenders to work out a settlement often find themselves flummoxed as well. “It’s almost impossible to find a mailing address for these people, because their business is all online,” said Mona Rubinstein, an Ohio attorney who represents clients fending off creditors.

One of her clients filed for bankruptcy in 2018 after taking out loans from five fintech lenders in succession, beginning in 2013: LendingClub, Best Egg, SoFi, Avant, and SunUp Financial, leaving substantial balances unpaid to all of them. In her bankruptcy papers, she reported possessing $50 in cash and $30 in her bank accounts.

This is familiar territory for the woman, who reported earning about $58,000 a year working in human resources and has declared bankruptcy twice before. When she last filed for Chapter 13 in 2005, she had $3,831 in debts outstanding to eight payday lenders and check cashers; another $11,300 to consumer finance companies, the analog predecessors to the fintech lenders; and another $17,672 to various credit card, retail, and medical creditors — owing $32,803 in all, not counting money she owed on her home.

That credit history didn’t stop fintech lenders from approving her loan requests, however. All told, she’d piled up $82,140 in debts to the fintechs — nearly triple the amount she’d previously owed more traditional lending firms.

Austin-based BorrowersFirst is yet another fintech lender this woman is indebted to, for $14,272. But her lawyer Rubinstein can forget about working out a deal with the lender, whose former chair, New York City-based investor Neil Wolfson, once promised it would rival Prosper and LendingClub in size. BorrowersFirst, despite $400 million in investment capital and a partnership with Cross River Bank, is in bankruptcy too.

By pushing consumers to the brink, in pursuit of market share and returns for investors, fintechs are also pushing the limits of sustainable lending. It’s a business model that’s profitable — so long as more Americans dig deeper into the debt hole and enough have money remaining in their bank accounts to fulfill automatic payments. But it courts calamity when the well runs dry.