Jesse Harvey had one big idea left. Charismatic and outspoken, he was a graduate student of public policy at the University of Southern Maine and a prominent activist battling the drug war around New England. But after a multiyear stretch of abstinence, he had recently suffered a sequence of awful events: He relapsed with alcohol and drugs, got into a car accident, was arrested twice in two days, overdosed, entered a rehabilitation facility and then left early, and detoxed at a hospital.

Lying in a hospital bed in late 2019, he told his mother, Catherine Nash, that another stretch in a rehab center wouldn’t do the job. At just 27, he had already experienced the disillusioning cycle in and out of inadequate treatment facilities and hospitals that is familiar to the millions of Americans with substance use disorders. “Those places never work,” Catherine recalls him saying. He knew well that many patients quickly relapse after leaving standard treatment centers.

He told Catherine he wanted to enter civil commitment, a court-ordered form of institutionalization. Once Jesse agreed to be committed, he would be relinquishing his right to leave before a specified date. Catherine was relieved at his decision, desperate for anything to help her son, even if it meant he would be locked up. After a night in a motel and a pizza dinner, they drove a rental car through the snow to a courthouse in central Massachusetts.

Throughout the United States, people with diagnosed mental illnesses have long been voluntarily and involuntarily committed to treatment centers and hospitals. More recently, civil commitment has been used to treat people with addictions. Yet experts say that even if commitment can prevent self-harm in the short term, it rarely addresses the root causes of substance misuse — and its long-term consequences can be devastating. “Seclusion and restraint continue to be used in inpatient commitment settings, and the experience can be highly traumatic for some patients,” according to a 2019 report exploring the practice by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a federal agency.

There is little to no evidence demonstrating the long-term effectiveness of civil commitment for substance use disorder. Still, courts have repeatedly classified this form of incarceration as constitutional, seeing it as necessary for the safety of both the public and the individuals locked up.

Even when civil commitment is effective, it deprives people of basic civil liberties. “There is no real evidence that I’ve heard that convinces me that it’s reasonable to take away somebody’s freedom over their own body when they have not been convicted of a crime,” said Susan Sered, a sociologist at Suffolk University who has for years studied civil commitment for women and fears the rise of commitment for drug use. “The wholesale use of voluntary commitment is really going to be problematic. There is a reason that we have a legal system with the idea of due process.”

Overwhelmed with opioid overdoses, many states have loosened their civil commitment laws over the last decade to sweep in more people with substance use disorders. A yearlong investigation by The Intercept and Type Investigations — including dozens of data requests, examinations of obscure government records and databases, and interviews with numerous experts and patients — shows that in recent years, tens of thousands of people across the country at minimum have been forced to undergo addiction treatment in jail-like conditions. While some of them benefit from civil commitment, others find the treatment to be nonexistent or downright harmful — and all lose their freedoms while they are locked up. The facilities holding them are sometimes housed on the grounds of jail complexes, providing incarceration by another name.

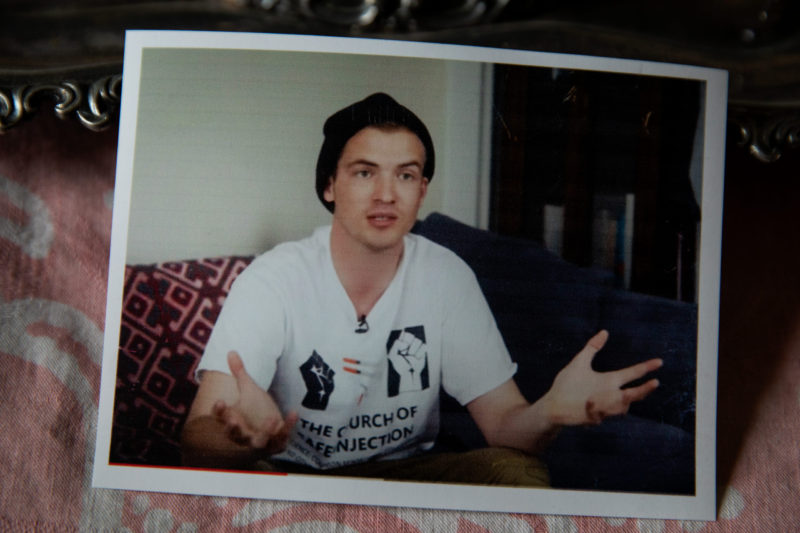

Jesse had tried civil commitment years earlier, doing a 25-day stint at the Massachusetts Alcohol and Substance Abuse Center. Despite its harshness, he had found the intense structure helpful and wanted to try it again. Starting at a young age, he had spent years tackling the challenges of addiction — both for himself and for others. At 24, he founded a nonprofit that ran recovery houses, and at 26, he started the “Church of Safe Injection” to offer supplies like unlimited free clean needles to those in need.

Catherine Nash holds a business card from The Church of Safe Injection, the harm reduction organization that her late son Jesse Harvery founded. Image: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept

By 2019, Jesse had become well-acquainted with the mountains of research showing that criminalizing drug use worsens the plight of users. He knew that successful treatment requires a combination of medication and therapy. He understood that he would be entering a locked facility when he put his fate in the court’s hands, but he anticipated a therapeutic environment as well. On December 31, Catherine and Jesse entered Leominster District Court, where she signed a form to commit him. The thin young man with clean-cut hair was still wearing his hospital scrubs when a forensic psychologist from the state’s Department of Mental Health assessed him. (The department’s slogan: “Good Mental Health. It starts with a conversation.”) Jesse’s breath smelled of the booze he’d had that very morning, but the psychologist found him to be articulate and intelligent. She agreed that he met the state’s criteria for commitment — he’d lost his ability to control his use of alcohol and drugs, and he posed an imminent threat to himself or others — and a judge signed off.

Massachusetts has one of the highest rate of deaths from opioid overdoses of any state. It also has among the most commitments in the country, and the state Department of Correction runs the largest program. Jesse joined the thousands of people committed in the state in 2019. For the first time in a while, he was optimistic about his chances at transcending his disorder. He asked to go to the Stonybrook Stabilization and Treatment Center in Ludlow, where he knew he would be held until he was sober. “He just needed to be in a place where he couldn’t leave,” Catherine recalled. At the time, the average stay at Stonybrook lasted 52 days, much longer than at other facilities in the state. Yet based on his previous experience in commitment and the advice of a public defender, whose name does not appear in Jesse’s treatment records, Jesse believed he would be locked in the treatment center for about three weeks, which had been the statewide average length of commitment a couple years prior. After that, he hoped, he could return to school, healthy and with renewed spirits. It didn’t work out that way.

A photo of Jesse Harvey that his mother Catherine Nash keeps on display in her home. Image: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept

In the modern era, civil commitment laws are primarily used to treat individuals with severe mental illnesses, but states are increasingly applying the laws to other populations. Individuals can be committed while being evaluated for competency before they stand trial, for example. Other people are held in commitment indefinitely, sometimes for decades, after completing criminal sentences, a practice opposed by the American Psychiatric Association.

Individuals who use drugs inevitably were added to this population. As part of the panic over cocaine and crack, especially among pregnant Black women, in 1989, the first Bush administration recommended that states make it easier to civilly commit drug users. (At the time, only a handful of states had civil commitment programs for people with substance use disorders who hadn’t been convicted of a crime, and the laws were rarely used.) In 1997, the Supreme Court expanded the conditions under which people could be civilly committed, ruling that it was legal to commit anyone who had a “mental abnormality,” whereas the previous standard had been narrower, requiring “mental illness.” Writing in the California Law Review in 2002, a law professor predicted that the ruling would expand civil commitment for substance abuse, despite its violation of fundamental due process rights.

That’s exactly what happened. As of May 2021, 37 states and the District of Columbia permit civil commitment for substance or alcohol misuse, with additional states considering joining the ranks, according to data from Temple University’s Center for Public Health Law Research. Between 2015 and 2018 alone, there were 25 new laws — or expansions of existing laws — in this area. That was more than triple the number of new or expanded laws passed in the 13 prior years combined.

While some states’ laws are less restrictive than others, many of them lead to warehousing people with substance misuse problems in jail-like facilities that can, in some cases, exacerbate rather than address their illness. “There is an increasing recognition that incarceration may not be the appropriate response to addiction, but at the same time, the rapid growth of civil commitment laws and programs is an indicator that we’re not moving away from negative, coercive programs — we’re just rebranding them,” said Leo Beletsky, a public health expert at Northeastern University School of Law.

Many states lack data on how many individuals are committed exclusively or primarily for substance misuse, instead folding the numbers into the total number of people committed for all mental health issues. In Texas, that number is astronomical: There were more than 240,000 applications for commitment between fiscal years 2016 and 2020. Of cases that reached a final hearing, about 60 percent were ordered to inpatient commitment, with the numbers of annual commitments tripling from 2004 to 2020. Wisconsin, also high on the list of states that commit people, had about 17,200 cases between 2016 and 2020.

Massachusetts leads the country in confirmed substance abuse commitments, with nearly 30,000 adult cases of commitment between FY 2016 and FY 2021. Minnesota issued more than 5,200 judgments between 2016 and 2021 ordering that people be committed. In Kentucky, there were almost 3,000 cases of people being committed between 2016 and 2021, while Washington committed about 300 people for opioid use disorder between April 1, 2018, when the state’s commitment law went into effect, and December 31, 2021.

Florida’s commitment law for alcohol and substance use disorder was used nearly 45,000 times between January 2016 and June 2020. But it’s impossible to know how many of those cases actually led to commitment, because the state doesn’t track that number. “This should not be particularly difficult to investigate or to see,” said Ameet Sarpatwari, an expert on bioethics at Harvard Medical School. “The stats haven’t really been collated in a systemic way across the states, and states aren’t necessarily collecting that information and making it transparent.”

In some states, civil commitment laws are on the books but rarely invoked for substance abuse. In Michigan, an average of one person a year is committed for it. But that isn’t because policymakers don’t wish to lock people up; 80 percent of judges in one survey said they had seen individuals who would benefit from commitment for substance abuse. However, when someone signs a petition for civil commitment in the state, they must agree to cover the costs of examining their loved one by a health professional, pay for the court hearing, and the commitment itself. That discourages people from utilizing the program.

The lack of comprehensive national figures on civil commitment for substance use disorder illustrates what Nathaniel Morris, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, has called “detention without data.” He says it applies to civil commitment generally, not just as the practice is used for substance misuse. “Even within states, civil commitment may be practiced differently between different counties,” he wrote in an email. “We have a fragmented mental health system in the United States, where different hospitals, emergency departments, clinics, and courts often do not readily share information or communicate with one another.”

Nearly all states mandate that individuals receive a clinical assessment before they are committed. However, in one recent survey published in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 19 out of 33 court clinicians surveyed in Massachusetts who evaluated people for substance use disorders said they had at least once recommended that an individual be committed even when they didn’t meet the statutory criteria for it — that is, they went beyond what the law allows. And only four states bind the court’s decision to the assessment.

These kinds of arbitrary standards and lack of oversight alarm doctors, activists, and experts, many of whom are fighting the expansion of laws that would allow more involuntary commitment. Some believe civil commitment for opioid users should be abolished altogether, while others believe it needs profound reform.

Jesse Harvey was just glad to be going somewhere he could get the help he needed. That was the plan anyway.

A view of the Hampden County Sheriffs Department/Correction Center and Stonybrook Stabilization and Treatment Center, on March 19, 2022, in Ludlow, Massachusetts. Image: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept

The Hampden County Sheriff’s Department depicts Stonybrook as an ideal treatment center, promising “evidence-guided, trauma-informed, and family-focused detox and post-detox care.” It describes a therapeutic, nonpunitive environment. “The men civilly committed to [Stonybrook] are referred to as clients,” it says. They are issued T-shirts, khaki pants, and sweatshirts to wear and don’t share space with people who face criminal charges: “Civil commitments are housed separately, their intakes occur separately, and have all recreation separately.”

But Jesse soon discovered a very different reality. Like other individuals committed in Massachusetts, he was immediately slapped with handcuffs and shackles for transport to the treatment center, though he had volunteered to enter commitment and hadn’t been charged with a crime.

While there were dedicated therapists on staff, Jesse was also surrounded by jail guards, a policy that Rob Rizzuto, a spokesperson for sheriff’s department, said has since changed. “All staff working at the Stonybrook Stabilization & Treatment Center are specially trained residential treatment staff,” he wrote in an email. Yet he acknowledged that some of the people classified as residential treatment staff are former correctional officers. The building itself is on the grounds of the Hampden County Correctional Center, a forbidding seven-building complex that holds 900 medium-security prisoners and is surrounded by barbed wire. In a 500-page diary he kept during his stay, Jesse described the humiliation of being locked in a jail-like facility run by a sheriff. “This is the best way to reinforce criminality and to hopelessly institutionalize the already downtrodden,” he wrote.

Guards routinely called the men “inmates,” he wrote in his diary, flouting the official policy, and the language of incarceration also appeared in his treatment records. In Jesse’s “offender assessment” documents, his caseworker referred to him as an “offender” who “is in jail” and in “incarceration.” He was given a wristband with an ID number and barcode. His cell was a shared room with a stainless steel seatless toilet and an open door that allowed the guards to monitor him at all times. (Rizzuto said that “the program has since moved to another facility which has communal bathrooms with modifications made to enhance privacy.”) Jesse was given shirts with slogans like “Change is Possible” and “Recovery Works.”

Stonybrook’s rules added to Jesse’s sense that he was being locked up for having an illness. “It’s dehumanizing and unnecessary,” he wrote. “Put us in a hospital or a treatment center, not a jail.” The jail could arrange for family visits by special appointment only, and staff monitored detainees’ phone calls, which they could only use to call pre-approved individuals. After granting them five free five-minute calls upon entering the facility, Stonybrook charged the usual exploitative call fees common to prisons and jails in the U.S. (the policy at Stonybrook has since been changed to permit 15 free 10-minute calls per week). The jail only accepted letters sent to residents that were written on white paper in black ink and sent in white envelopes. Although they received snack bags, there was no commissary should detainees want to purchase extra food, beverages, or hygienic items (in an April 2019 presentation, the sheriff’s department said this was meant “to prevent the clients from placing undue pressure on family members for money,” claiming that many of them “have been a financial drain on family resources.”)

In response to emailed questions, Rizzuto praised the program. “We are extremely proud of this program as it has saved countless lives as the addiction treatment system offers too few options, and insurance is a barrier to many getting the comprehensive help they need and deserve.” He added that, since Jesse’s time at Stonybrook, there is a new recreation area with open outdoor spaces, a large lawn, basketball courts, a track, and a wooded area. Stonybrook now has a full-time therapy dog, Rizzuto said, as well as more mindfulness classes, including a guided drum circle.

But Jesse wasn’t the only person who experienced commitment in Massachusetts as dehumanizing. A 2019 lawsuit filed by Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts, or PLSMA, against several state agencies alleges that people committed in the state were put in shackles and waist chains, subjected to strip searches, and even put in solitary confinement — all outside the criminal justice system. In 2021, the organization filed an amended complaint, adding four men held in Stonybrook. The suit is still pending.

“The feedback we receive from patients and their families is not at all consistent with the allegations made in the lawsuit,” said Rizzuto, who denied that the department conducts strip searches or uses solitary confinement. “We often hear from clients and their families that our program saved their lives.”

Spokespeople for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Department of Correction, and the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security all declined to comment, citing pending litigation. The Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to requests for comment. But the agencies mentioned by PLSMA jointly filed a court motion in February 2022 seeking dismissal of the suit, noting that the state is requesting $36 million to overhaul one of the civil commitment facilities. The motion said the state “is involved in major, ongoing projects to improve” the program.

Despite his shock and disappointment at his treatment, Jesse was determined to make the most of his experience. “There’s some pain in my life that I haven’t addressed yet, that I should, that I must, if I hope to recover,” he wrote. He was eager to receive counseling and explore research-backed treatments. He meditated often, read a mystery novel, found himself enjoying the news and classical music on NPR, and he watched NBC’s “Meet the Press” and several Keanu Reeves movies in the common space.

Some fellow detainees recognized him from his activism and approached him, he wrote in his diary, and numerous others who had read or heard about his work sent him letters. “He was a visible and beloved figure in harm reduction communities,” said Northeastern University’s Beletsky. After working at a treatment center in Maine, Jesse had founded his nonprofit, Journey House, which operates four homes for people in recovery, addressing the need for affordable housing for people taking medications to combat substance abuse issues. Rehab, halfway houses, and treatment centers in the U.S. are traditionally abstinence-only, prohibiting or ejecting anybody who uses drugs like methadone that are proven to help alleviate withdrawal symptoms and psychological cravings. But Jesse knew about the growing body of research that suggests that such strict puritanical mandates are deeply harmful to recovery, and his recovery houses reflected that knowledge.

That’s also what inspired him to found the Church of Safe Injection. In Maine, where it was illegal to independently distribute clean needles despite overwhelming evidence that it saves the lives of intravenous drug users, Jesse handed out thousands of them in areas where addiction was rampant. The Church spread to other states and had multiple chapters. Soon Jesse was profiled in HuffPost, STAT, various Maine publications, and a short documentary film.

Helping other residents was a source of strength for him while at Stonybrook. He encouraged his cellmate to take advantage of after-incarceration support systems and talked with another about opening a sober house together. “I have a feeling I am here for a reason, not only in this facility but on this planet and in this multiverse,” he wrote in his diary.

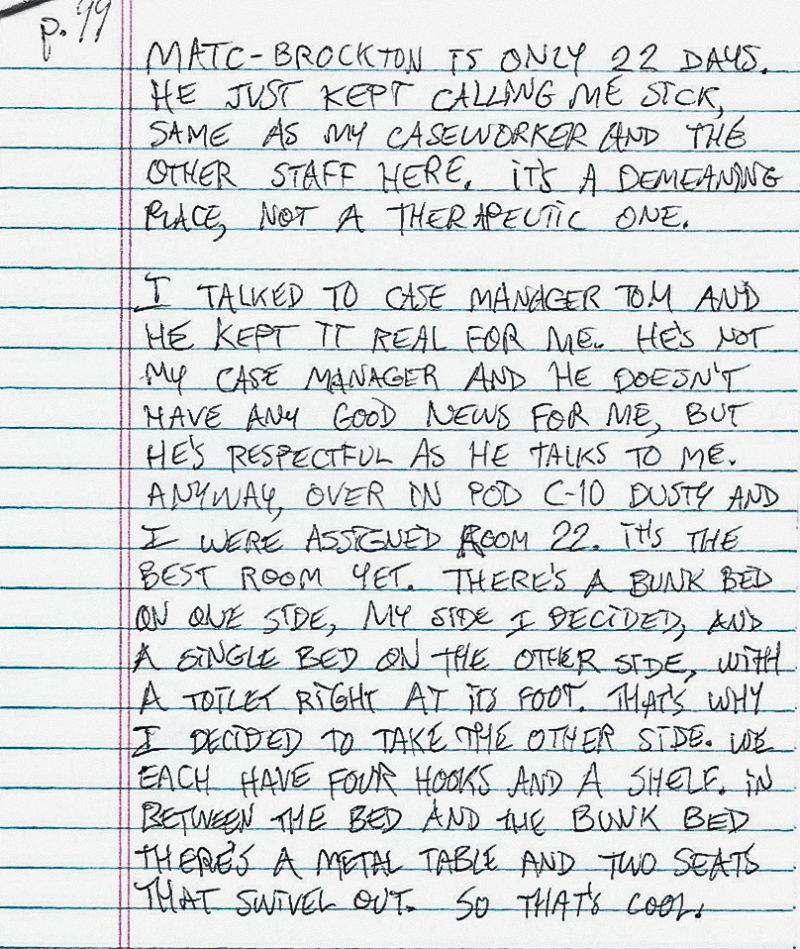

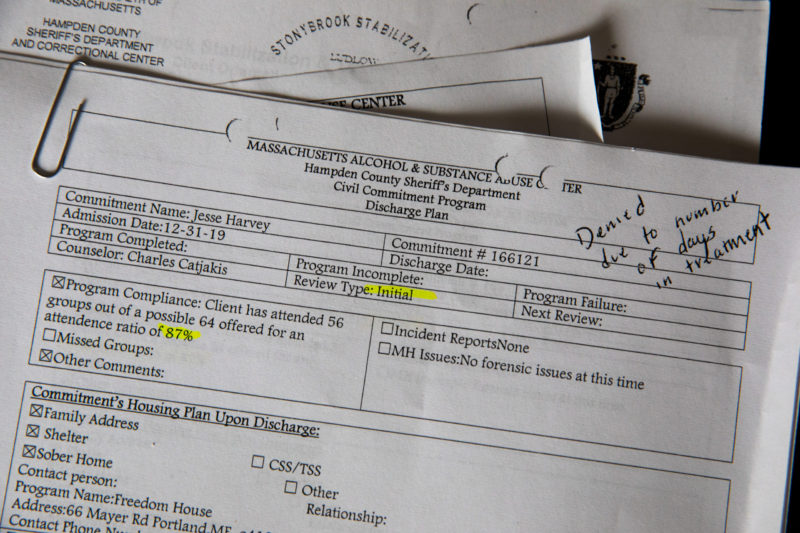

But Jesse’s extensive knowledge of treatment options made his experience all the more disappointing — and then infuriating. Most of the treatment at Stonybrook came in the form of group meetings, which he was pushed to attend, even if they were unhelpful. “Another group providing little if any therapeutic value,” Jesse wrote after one meeting. “It’s a demeaning place, not a therapeutic one.”

Image: Obtained by The Intercept

His impressions were echoed in the PLSMA lawsuit, in which one prisoner alleged that he was forced to withdraw from opioids cold turkey, and another claimed that none of the treatment sessions tackled the mental health problems underlying substance misuse. Rizzuto did not address the lawsuit claims directly but said, “All clients are seen by medical staff upon admission for a physical evaluation to include medically managed withdrawal specific to each client’s needs.” Stonybrook provides medication to help people detoxing, Rizutto noted, in the form of Suboxone, Librium, Vistaril, and clonidine.

In his diaries, Jesse noted that some detainees were benefiting from the treatment offered, and he said being away from dangerous substances was initially helpful. Still, he wrote, “I wonder why such rehabilitation, court-ordered, can’t happen exclusively in hospital settings, locked even, and why can’t it happen in line with compassion and evidence-based principles instead?”

Jesse soon found that whatever benefits he derived from civil commitment were diminishing. He was horrified to learn that he would not be leaving after three weeks. Instead, he was told he would be released at an unknown date entirely at the discretion of the facilities’ officials. (Treatment records show that Jesse’s commitment was meant to expire on March 27, nearly three months after his commitment.) “Part of me is starting to wonder if I’ll get even more jaded, or depressed even, if they don’t let me leave soon,” he wrote. But getting out would prove far more difficult than he could have imagined.

Documents from Jesse Harvey’s stay in the Hampden County Sheriff’s Department Civil Commitment Program and Stonybrook Stabilization Center are seen at his mother Catherine Nash’s home on March 17, 2022. The document on top shows that he was denied release. Image: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept

As the opioid crisis escalated, it was easy for policymakers to opt for civil commitment as a remedy. For one thing, after decades of mass incarceration, jails and detention centers are more plentiful and better funded than outpatient services that treat drug addiction and dependency. Locking people up is also a simpler policy option than dealing with the structural factors that lead to drug and alcohol misuse, such as poverty. Civil commitment also doesn’t infringe upon the rights or privileges of the general public, and politicians can boast that they are taking action as part of the drug war.

“There has long been this idea that if you criminalize homelessness, and if you criminalize mental health conditions, then you don’t have to actually deal with it,” said John Raphling, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch, which last year opposed a proposed civil commitment bill in Yolo County, California. “It’s easier for a given community to say, ‘Well, just lock those people up on the street.’” In one county in Florida, 1,000 people are committed per year — but there are only 20 beds for long-term treatment. The rest are sent to jails.

Depending on the state, mental health providers, court officials, or law enforcement can apply for commitment. Many states also allow any member of the public to file a petition for commitment. Between punitive laws criminalizing drug use and the lack of affordable treatment options, civil commitment may seem like a reasonable last resort for familie watching loved ones succumb to addiction. “Given the realities of fiscally constrained public mental health systems in an era of managed care and a shrinking safety net, commitment is being used to leverage scarce resources for treatment and other services,” as the 2019 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration report put it. Black people are especially unlikely to receive treatment for opioid use disorder, one reason African Americans are overrepresented in civil commitment.

Effective treatment elsewhere is rare; a survey of 613 for-profit and nonprofit treatment programs published in 2020 in the medical journal JAMA found that not even one-third offered opioid agonist therapy, which research has shown is effective at reducing the risk of overdose and relapse. Well-resourced hospitals and mental health clinics are even scarcer, making civil commitment a more attractive option.

But there is skepticism in the medical community — and sometimes outright hostility — about the use of involuntary treatment for opioid users. In a survey of 739 American Psychiatric Association members published in a 2007 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, just 12 percent supported committing people for drug use. Still, the approach has its supporters. A 2021 paper in the Journal of Addiction Medicine found that 60.7 percent of addiction specialists favored the practice, although more than one-third of those surveyed said they were unfamiliar with how the laws even worked.

There is good reason for clinicians’ and researchers’ ambivalence. “There is limited quality, peer-reviewed research on the efficacy of involuntary treatment for alcohol and substance use disorders,” according to a 2019 report by a commission appointed by Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker. Proponents of the practice sometimes suggest that, if nothing else, civil commitment provides a short-term way to keep people from overdosing. But a full one-third of civil commitment users relapse the same day they are released, according to a study in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence. The evidence also suggests that forcibly detaining people for opioid misuse doesn’t work in the long term. A paper on civil commitment in a 2021 issue of the Journal of Medical Ethics found “emerging evidence suggests that it may be associated with long-term harms, including a heightened risk of severe withdrawal, relapse and opioid-involved mortality.”

“Involuntary civil commitment is the opposite of treatment,” said Michael Sinha, an adjunct professor at Loyola University’s Beazley Institute for Health Law and Policy, in an email. “In a therapeutic relationship, patients have autonomy and must provide informed consent prior to commencing any treatment or procedure. In a coercive setting such as involuntary civil commitment, patients have no autonomy to affirmatively choose treatment.”

The criminalization of commitment compounds its essential illiberalism. Bonnie Tenneriello, an attorney with Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts who worked on the lawsuit, sees a clear violation of due process. “You can’t hold men in prison just because they have an addiction,” she said. “It’s disability discrimination, it reflects decades of misconceptions about addiction, it creates stigma.”

Image: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept

Jesse Harvey experienced the criminalization of drug addiction firsthand, and he wanted out. Besides his frustration with the treatment, Jesse had other reasons to get back home. He needed to return to his final semester of graduate school or else risk losing his health insurance, access to his counselor and psychiatrist, a $2,000 academic scholarship, and a salary working part-time on campus. “I can get these things back if they let me out,” he wrote. But it’s difficult to revoke a civil commitment in Massachusetts. Stonybrook officials were unmoved by his appeals, with his caseworker writing in his notes, “Jesse seems more focused on leaving our program than committing to treatment.” Another recorded, “I tried to point out to Jesse that he needs to focus on his treatment and recovery and [he] seemed to feel that he is not receiving any treatment here at Stonybrook.”

Jesse’s diary entries grew increasingly despondent. “It is tremendously disempowering, coming to a facility that we’re supposed to get better at, regain our self-esteem, etc., and then be talked down to, lied to, misdirected, etc., constantly having our autonomy and our hopes and dreams torn down without any thorough evaluation of their merit by staff,” he wrote.

He started gathering signatures from other detainees to protest conditions, suggesting they form a class-action lawsuit. “When I’m stuck in a mindless bureaucracy that pledges itself more to red tape than results, I like to fight,” he explained. His efforts did not endear him to authorities. He wrote in his diary that the guards stopped giving him paper, envelopes, and pens, though the sheriff’s department denies this.

At his three-week mark, Jesse was transferred to the Western Massachusetts Recovery and Wellness Center, another facility run by the Hampden County Sheriff’s Department. There, at least the toilets had seats. But again, according to Jesse’s diary, he didn’t find the available treatment to be helpful. “A lethal shame,” he called it.

He wanted to attend different meetings, return to seeing his therapist, get regular exercise, and volunteer or get a job somewhere. He felt that he had a better support system on the outside, with his family, friends, and graduate studies. He made a bucket list of life experiences he wanted to try, everything from bungee jumping to hosting an art show to running a restaurant. He also pledged that, once he was released, he would work to improve conditions for other people in civil commitment.

The Massachusetts statute governing civil commitments authorizes superintendents to release individuals at any time if it does not result in “serious harm” to the community. Yet the office of Superintendent Pamela MacEachern denied his request to leave. (MacEachern has since retired and the spokesperson for the Department of Correction, Jason Dobson, said privacy laws prevented him from commenting on “any part of an inmate’s incarceration.”) Harvey wrote a letter to the sheriff, Nicholas Cocchi, saying, “I’d like to talk to you about concerning violations of civil rights” as a result of his release request being denied. Cocchi responded that he had reviewed Jesse’s case, offered to speak with him, and wrote, “I recommend you continue to work toward your discharge plan.”

A shrine for Jesse Harvery, created by his mother Catherine Nash. She sits at the shrine every morning and remembers Jesse while looking at the various mementos. Image: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept

Jesse began a hunger strike, refusing all food and beverages besides water and coffee. Still, authorities refused to release him, transferring him back to Stonybrook in handcuffs. He sat in his cell reading and meditating. When nurses checked on him, he declined medical treatment. Other prisoners, including his cellmate, ridiculed him for starving himself, he wrote in his diary, but he was adamant.

Finally, after 124 hours, Jesse wrote, he was given an ultimatum: He had to immediately consume a meal-replacement drink or be put on “risk status,” meaning he would be placed in an anti-suicide smock, and put on continuous 1:1 observation if he refused to wear the smock. However, if he ate, staff promised to review his case status again in a few days. He was convinced the superintendent would let him die rather than release him. He drank the beverage and was put into a wheelchair.

Jesse attended the necessary meetings and outwardly welcomed the treatment he felt was useless. “I can’t believe how powerless I am here,” he wrote. “They have sufficiently beaten me down into dirt. All I feel is worthless. All I see is metal bars. All I hear is lies and dogma and broken promises.”

Stonybrook authorities saw Jesse’s eventual compliance as evidence of progress. He was released on February 6 and given a “certificate of participation,” five weeks after he was first committed and one week after his hunger strike ended. He described feeling battered by the experience. The day before he left Stonybrook, Jesse confessed in his diary, “I feel like I’ll be out and still not feel like it’s real, still feel like a person who is unworthy of civil rights, let alone ethical treatment and common courtesy.”

Kari Morisette met Jesse at the first recovery meeting he attended post-release. Morisette told the group that she felt purposeless, living paycheck to paycheck and working at a donut shop. Jesse approached her after and invited her to help him hand out clean needles to drug users. “He had that type of personality who drew people in, so I didn’t know him, but I knew that I wanted to know him,” she recalled, in between running deliveries for the Church of Safe Injection. She is now the Church’s executive director.

The two became fast friends, and he schooled her in the ways of harm reduction. “It was just me and him,” she said. Jesse remained sober for a while but soon began drinking again. He was discouraged and angry at what he had endured, and he grew more isolated. He was more convinced than ever that the punitive response to substance misuse was both ineffective and caused immense suffering. On September 7, 2020, about seven months after leaving Stonybrook, Jesse died of a drug overdose in his home.

Catherine Nash poses for a portrait with a quilt made from harm reduction and recovery related t-shirts that her late son Jesse Harvey gave her. She lays under the quilt every morning and reads the messages on the t-shirts to remember him. Image: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept

Experts say that Jesse’s experience is common. At worst, civil commitment can cause trauma among people suffering from substance use disorders, who are further discouraged about the health care system. Harvard’s Ameet Sarpatwari, who has written about civil commitment of opioid users for The BMJ, a medical journal, said that treatment in such institutions is often lacking. “It would be one thing if you brought them into care and provided them with the gold standard of care. And then ensured that once they were released from somewhere, that they had integrated and continuous care,” he said. “But that’s not what we’re seeing.”

Catherine, Jesse’s mother, is furious at the civil commitment authorities in Massachusetts. “Jesse died a preventable death,” she said in an email. “Being forced to wait so much longer than he needed to in that diabolical cell week after week took away the things he had to live for.”

But in Massachusetts and nationally, authorities are keeping faith in civil commitment. The Colorado legislature is considering expanding its program. The Washington state legislature recently passed a bill allowing law enforcement and social service workers to petition to require people to undergo outpatient treatment for substance use disorder. This would further criminalize drug use and ensnare even more people in the criminal justice system.

If Jesse had lived, he might have fought against such programs. In his diary, which his mother shared with me, Jesse asked, “How can any sane society or government sanction the jailing of any person who has not committed a crime, but rather has what they — and society and the state — have said is a disease?” He also pointed out the irony of commitment as care. “The power differential that is inherent in a situation like this is glaring and dangerous,” he wrote. “They are taking away the supports they say you need.”

This story was reported with support from the Puffin Foundation.