This story is part of the Inside/Out Journalism Project by Type Investigations, which works with incarcerated reporters to produce ambitious, feature-length investigations, with support from the Puffin Foundation.

Donald “Curly” Brooks lifted his shirt and stared intently into the mirror of his prison cell. The warped, thick metal never gave him a clear picture of himself. In his 45 years inside prisons across the state, he rarely saw his image clearly reflected. It didn’t help that a deteriorating eye condition left him legally blind.

Still, he could see something was wrong. He pinched loose flesh near his waistline and commented matter-of-factly, “l think I’m dying.”

Brooks, 64, once struck an imposing figure inside Mule Creek State Prison, where he’s been housed since 2017. He is over six feet tall and usually weighs 250 pounds, with a head that many say looks like an oversized bowling ball. But in mid-2023, he began losing weight at an alarming rate, about 50 pounds in three months. An acute pain in his side sent him to the prison’s medical clinic.

When the doctors checked Brooks for kidney stones, they also discovered he had kidney cancer.

But they couldn’t tell Brooks how or why he contracted it.

Others had dealt with similar illnesses they didn’t have before arriving at Mule Creek – kidney issues, cancer, men on thyroid medication, some for life. Some experienced rashes, gastrointestinal ailments, extreme bouts of haziness, and fatigue. People suspected the water. Brooks had been to eight other prisons before this one, and some had posted water quality notices if there were safety concerns. At Mule Creek, he never saw those. But men complained that the water often tasted off or looked cloudy. Black residue developed around people’s glasses and water bottles overnight.

For decades, people incarcerated at Mule Creek have raised the alarm about the prison’s drinking water. Reporting from inside Mule Creek State Prison, with interviews and surveys from nearly 100 people—including currently incarcerated, formerly incarcerated, loved ones of the incarcerated, and former prison staff—and a review of thousands of pages of records reveal troubling concerns and observations of the prison’s water quality for the last 20 years. Many reported illnesses during their time of incarceration, ranging from mysterious rashes to life-changing diagnoses that studies link to exposure to environmental pollutants. People living near the prison have been exposed to dangerous chemicals in their well water, and investigators have discovered severely corroded pipes beneath the facility. Guards bring bottled water to work. Contractors have gotten sick on the job.

Despite this litany of warning signs, including repeated complaints and lawsuits, the prison has deferred responsibility. California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation officials say the local water company is responsible for ensuring the water is safe; the water company says state regulators are responsible; regulators say it’s the prison’s responsibility. All the while, incarcerated people at Mule Creek have no choice but to drink it.

The first signs of concern

The roots of Mule Creek State Prison’s water problems date back to 1985, when the state broke ground on the 866-acre carceral compound in rural Amador County. The project was part of an explosive, fast-paced prison-building boom set off after California voters approved the issuance of $495 million in bonds to remodel old prisons and build new ones. The state’s embrace of mass incarceration created a growing demand for new prisons, as well as an opportunity to bring jobs and investment to rural communities. But construction and equipment related issues in new prisons were common, and there were specific concerns about the environmental impact of Mule Creek State Prison before it was built.

Mule Creek State Prison became a hub for the growing California Prison Industry Authority. In addition to housing units meant to cage 1,700 people, on-site facilities would come to include coffee roasting, meat packing, lunch packaging, building maintenance, welding, sewing, textile manufacturing (including the manufacturing of CAL FIRE gear), a large laundry operation, and a dry cleaning plant.

Many of these industries produce toxic chemicals. But currently and formerly incarcerated people describe prison workplaces with few safety standards or protections. For years, they say, harsh chemicals associated with these industries were not properly treated and were dumped down the drain. And as the prison’s population grew, the facility’s wastewater treatment plant struggled to keep up. In 2006, the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board wrote that the plant was “severely overloaded, resulting in wastewater not being adequately treated.”

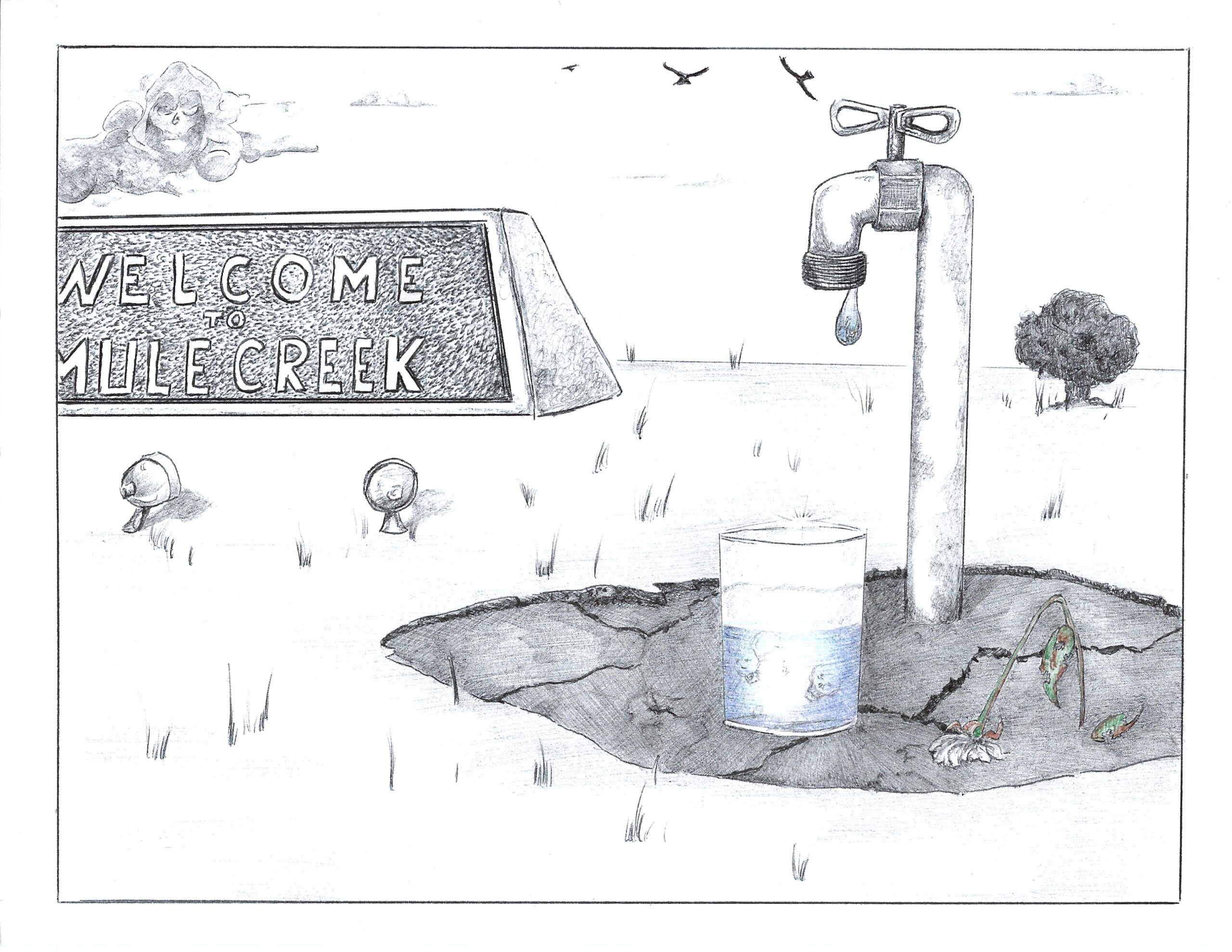

Mule Creek State Prison Image: Emily Nonko

That year, residents living near the prison began complaining that black water was flowing into the creek. One landowner tested the water in the creek and found coliform bacteria as well as caffeine, which he suspected came from the prison’s coffee-roasting plant.

Tests of wells supplying water for drinking and irrigation to nearby homes yielded even more concerning results: Three wells had high levels of nitrates, leading county officials to warn residents that infants who drink the water “may quickly become seriously ill and, if untreated, may die.” The irrigation well tested positive for the dry-cleaning chemical PCE, which studies link to cancer, kidney disease, and liver problems.

The prison warden at the time, Richard Subia, who agreed to shut down the dry-cleaning operation and paid for a resident to get off the well water, later told the Sacramento Bee, “If there’s a guy standing across the street with a smoking gun, and a person across the street who is lying on the ground, how much do you want to wait for?”

Although the dry-cleaning plant was closed, other industrial work at the prison continued, and Mule Creek also expanded.

Between 2014 and 2016, the CDCR built 24 new buildings on top of a “spray field,” where CDCR had disposed of treated sewage from the prison. According to state water officials, the expansion further strained the prison’s sewage disposal capacity. These officials also raised the concern that Mule Creek’s wastewater treatment plant was not designed to treat contaminants from the prison’s industrial operations.

Some answers finally came in early 2018, when the Regional Water Quality Control Board opened a new investigation after receiving a new complaint about contaminated water flowing into the creek. Again, tests of local wells uncovered contaminants possibly linked to the prison, including benzoic acid, a chemical used in meat processing.

State officials ordered CDCR to conduct a review of the prison’s stormwater and sewage drains to pinpoint sources of contamination. A 16,000-page report by SHN Engineers & Geologists, the consultants hired by CDCR to examine the pipes, offered a rare look into the prison’s inner workings. It uncovered over 500 defects in the prison’s stormwater and sewer systems, ranging from minor corrosion to broken and collapsed pipes.

The Regional Water Board highlighted even more concerns, which they felt the report downplayed. Some of the iron sewer pipes were severely corroded, a cause of “major concern” among board staff. Though the report said the corrosion was “typical” given the age of the pipes, the water board came to a different conclusion: The sewer and stormwater pipes beneath the prison were leaking so severely that much of the piping was likely “submerged in groundwater year-round,” speeding up the corrosion process.

The report’s revelations helped spark two environmental lawsuits, leading to a 2023 consent decree in which CDCR agreed to undertake repairs to the prison’s drainage systems and improve staff training on waste disposal practices.

These repairs, however, only address the prison’s stormwater and wastewater systems, which were leaking sewage into the creek. Sources familiar with the prison’s pipe system say that the domestic water lines (which carry sanitary and drinking water) are too close to sewer lines in some places, which risks cross-contamination. A longtime staff plumber described the system as if “they took a bunch of spaghetti, just threw it in a hole, and tied the ends in.”

Only a few paragraphs in the 16,000 page SHN report addressed the prison’s domestic water — and one finding suggested possible contamination.

SHN tested the facility’s domestic water on two occasions in 2018. In a summary of the results, the company raised no red flags and said that most of the substances for which they tested the water were present only at “nominal” levels. But bizarrely, one drinking water sample apparently contained oil and grease.

“Oil and grease” refers to a single pollutant that is often present in industrial and household wastewater. Type Investigations and The Appeal shared the results of the domestic water testing with seven academics who specialize in drinking water safety, including professors of civil and environmental engineering. Several specialists said that oil and grease is not typically found in drinking water at such a high concentration. While some said it was hard to draw many conclusions about the significance of this finding, others noted that the oil and grease could indicate possible contamination and merited further investigation.

The SHN report is dismissive of the oil and grease detected in the water sample, saying that “it is likely due to the geology of the area,” which contains a type of coal. Several of the specialists we spoke with were skeptical of this interpretation.

Carsten Prasse, an associate professor of environmental health and engineering at Johns Hopkins University who studies drinking water contaminants, said that, in his opinion, the presence of oil and grease was “definitely concerning as it indicates a potential contamination of the drinking water.”

“Oil and grease can be a lot of different things and from a lot of different sources. Depending on the source, the presence of oil and grease might also be associated with other contaminants of health concern,” Prasse added.

CDCR declined to respond to specific questions about these experts’ opinions, the nature of the water testing, or incarcerated people’s allegations of contamination. Instead, a spokesperson told The Appeal and Type that Amador Water Agency, the local water utility, is responsible for drinking water at the prison and said any questions about the water quality should be referred to AWA. “AWA meets all the health requirements set forth by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the California Department of Health Services,” a CDCR public information officer wrote in an email. “The quality of the water is monitored continuously at the treatment plant and in the distribution system.”

Foul, fishlike, and sulfurous

Amador Water Agency says it supplies clean, treated water to Mule Creek State Prison, where it is held in tanks. “AWA’s responsibility ends at the water meter to Mule Creek State Prison,” a spokesperson said.

A survey of 39 people incarcerated at Mule Creek, as well as interviews with 23 additional currently and formerly incarcerated people, paint a concerning picture about what comes out of the tap.

Thirty-seven survey respondents reported alarming qualities of their drinking water, ranging from issues with smell, taste, and appearance.

They described tastes that include chemical and fecal: “like iodine,” “like chemicals or metal,” “like crap,” “ shit,” “funky,” “bad,” “like you’re drinking out of a lake like a wild animal.” Smell descriptions included “foul, fishlike” and sulfurous.

They also described concerning appearances: “dirty brown,” “appears foggy,” “very cloudy,” “often gets a milky, white color.” Some respondents and interviewees said that a ring of black residue sometimes appears on their water bottle or drinking glass.

Amador Water Agency told The Appeal and Type that these descriptions fall under secondary drinking water standards, federal benchmarks for “aesthetic” qualities like the smell and taste of drinking water, and that the agency’s water “meets all criteria” of those standards.

Thirty-three survey respondents, and others interviewed — including former prison staff — say it is well known that the staff of Mule Creek State Prison do not drink water from the tap.

“There’s not too many people drinking the water there,” said Kirk Goodman, who worked as a senior radiologic technologist. A former contractor, who provided behavioral health treatment and requested to remain anonymous, said most staff know not to drink the water. “CDCR would never, ever — no one who represents CDCR — would ever warn you not to drink the water,” she said. “It would be someone on the side, kind of pulling you on your sleeve and saying ‘don’t drink the water.'”

While staff drink bottled water, incarcerated people have virtually no access to it. Bottled water can be purchased during prison visits, but incarcerated people cannot bring it out of the visiting room and back into the prison. Bottled water is not available for purchase at the prison commissary, incarcerated sources said, though soda is available. All 39 survey respondents said they drink water from the tap.

CDCR does provide a water quality assessment guide instructing state prisons on how to measure chlorine, pH, and temperature in order to ensure levels are sufficient to neutralize microbes that could cause disease.

Mule Creek State Prison has conducted these tests for chlorine, pH, and temperature. In response to a public records request for results of any tests of drinking water samples from the facility going back to 2021, CDCR responded with weekly water testing logs from the first half of 2024, saying they were “the only water samples for Mule Creek State Prison.” In response to follow-up questions asking why there were no records for other tests over the years, a spokesperson said they had located more water sample records but would not be able to provide them before publication.

Even so, drinking water contamination specialists say these tests are not gathering enough information to determine whether Mule Creek’s water is safe. While chlorine levels are a useful measurement for whether water contains harmful levels of bacteria or other microbes, they are not meant to reveal potential chemical contamination.

The tests “are not adequate to define water safety,” said Charlotte Smith, a microbiologist and water specialist who teaches at the University of California, Berkeley School of Public Health. “The USEPA lists over 110 constituents for which maximum contamination levels exist.”

CDCR has the means to monitor the safety of Mule Creek’s drinking water much more thoroughly. For several years, the agency has contracted with a laboratory for water testing at a group of prisons that includes Mule Creek. These agreements allow the prisons to request testing. Documents associated with the contracts show that CDCR considered testing the drinking water at these facilities for a wide range of contaminants.

Most of America’s prisons and jails have drinking water quality issues, David Pellow, a professor of environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told The Appeal and Type. Mule Creek is far from the only prison in California where staff avoid drinking the tap water at work. Meanwhile, across the state, incarcerated people have been forced to drink water containing arsenic, pneumonia-causing bacteria, and nitrates from agricultural run-off, resulting in serious medical problems and, in at least one case, death. Those cases were discovered or confirmed by testing prisons’ drinking water for contaminants. But uneven oversight allows many prisoners, like those incarcerated at Mule Creek, to fall through the cracks.

Illnesses abound

The scant testing makes it difficult to track or identify any specific hazards in the drinking water supply. But the people incarcerated at Mule Creek have been getting sick.

Image: Nathan Blalock/Type Investigations

Charles Gorton, who spent several years at Mule Creek in the mid-2000s, was an avid runner who had been healthy for most of his time in CDCR custody. That changed in 2006 — one year before Mule Creek closed its dry cleaning plant — and he started feeling “very, very sick.” He noticed strange symptoms, including intense swelling of his legs and ankles. Doctors diagnosed him with a rare kidney disease. He paroled in 2015, and needs daily dialysis as he waits for a kidney transplant.

Around the time that county officials told homeowners near the prison that their wells were contaminated, Gorton remembers seeing a paper bulletin appearing above the water fountains in the prison housing units that warned staff members not to drink the water and bring their own. Another formerly incarcerated person, who was at the prison at the same time as Gorton and worked as a clerk for a correctional officer, also recalled memos directing staff not to drink the water, though he couldn’t remember if the memos were publicly posted. Neither had any choice but to drink the water.

Gorton believes his illness is linked to the prison’s drinking water and to chemicals from the dry cleaning plant. The chemicals detected in nearby wells may be associated with kidney problems, studies have found. At the time Gorton worked for the prison’s “Plant Operations” crew, making eight cents an hour to work on plumbing and other general maintenance. He said he regularly worked on the prison’s piping system, which he recalled had at least eight breakages during the two years he spent as a maintenance worker.

In 2022, Kyle Whitesides, who is still incarcerated at Mule Creek, filed a formal complaint with CDCR demanding an investigation into the drinking water after he was diagnosed with a hypothyroid condition that requires him to be on thyroid medication for the rest of his life. He included a list of 28 other men who he said were also sick with illnesses he believed were linked to the drinking water.

“People were asking what was wrong with me, and in sharing my story with others it became apparent that a lot of others — a cluster — had similar experiences, liver cancer, thyroid cancer, hypo thyroid, and hyper thyroid, nodules, etcetera,” he told The Appeal and Type. He added that a significant number “had some form of medical problem relating to the thyroid.”

Whitesides may be right that there is a cluster. The Appeal and Type examined data collected by California’s Office of the Inspector General, the state’s independent prison monitoring agency. Since 2015, the office has reviewed medical records for nearly 7,000 “clinically complex patients with the highest need for medical services” at each facility across the state.

Our analysis found that Mule Creek has a higher rate of thyroid disease than any other men’s prison audited by the Inspector General aside from the California Health Care Facility, which CDCR described as a facility for those with the “most severe and long term” health needs. Mule Creek also has a higher rate of rheumatological diseases than any other men’s prison in the state. Research has linked exposure to environmental toxins to higher rates of thyroid disease and rheumatological diseases.

CDCR declined to comment on the health issues experienced by people incarcerated at Mule Creek.

Many of the men who responded to The Appeal and Type’s survey also mentioned medical problems involving the kidney and thyroid. Five respondents reported kidney problems, including nodules, cancer, and hyperkalemia. Eleven respondents reported thyroid problems—one person even had their thyroid removed after being diagnosed with cancer.

Whitesides is not the only person to attempt to raise the alarm to prison officials. Darren Sasser filed a grievance about the poor water quality and requested bottled water in 2024. He wrote to The Appeal and Type detailing his concern with skin discoloration, digestive issues, a rash, and viral meningitis while at Mule Creek. (CDCR has since transferred him out of the prison.) CDCR’s Office of Appeals denied the claim, writing “all relevant actions by departmental staff were proper regarding the water supply at Mule Creek State Prison.” Sasser says he appealed the decision until it was decisively closed this April: “Exhausting all administrative remedies available,” he reflected.

Matthew Cramer, who paroled from Mule Creek in 2021, says he filed multiple complaints with the CDCR about health and water concerns. He says he received rashes and sores after working on the yard; he was prescribed Dupixent, an injectable medication for eczema. He also shared concerns about his work on the yard and what he believed to be related health issues with an attorney representing the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance, which initiated the environmental lawsuit against Mule Creek.

Several formerly and currently incarcerated people said that prisoners do the bulk of the yard and plumbing work, for pennies on the hour, which can include exposure to the broken piping system. They say that incarcerated workers are often untrained, unsupervised, and lack proper safety equipment.

Xavier J’Weial (still incarcerated at Mule Creek) and Eric Hasting (formerly incarcerated at Mule Creek) worked on the prison’s yard crew. They say they witnessed safety issues with the pipes between 2017 and 2019. Around that time, they both got sick.

J’Weial experienced stomach pain, headaches, and nosebleeds, then received treatment for prolonged irritable bowel syndrome. “I was put on critical care treatment and given antibiotics,” he said, “That seemed to work, for a while.”

Hasting developed a severe rash; he recalls being prescribed heavy doses of the steroid prednisone. He also developed lumps on his body. “They said ‘oh, it was benign,’ and it might have been benign, but why did I get all these?” he wondered.

J’Weial and Hasting had no idea that just outside the electrified fence, contractor David Anderson had worked with his crew to build a culvert around the prison. By October 2017, he and his crew experienced a range of symptoms that worsened into the new year: muscle aches, joint pains, fatigue, dizziness, cough, wheezing, mental irritation.

Anderson shared his story with Jack Mitchell, the publisher and reporter of the local newspaper, the Ledger Dispatch. It sparked a series of in-depth articles on Mule Creek State Prison’s water issues, and also provided information for the environmental lawsuits against the prison.

Agencies deny responsibility

Incarcerated people have fewer pathways to raise alarm. The prison has repeatedly dismissed their concerns about the water and the possibility that it is linked to chronic illness.

CDCR denied Whitesides’ request for an investigation and told him to take up his complaint with the Amador Water Agency, which supplies the prison’s drinking water.

But Amador Water Agency, which told The Appeal and Type that the utility has received only two inquiries from incarcerated people in the last 18 years, insists that it supplies clean, treated drinking water to the prison. When The Appeal and Type attempted to track down who was responsible for water safety at Mule Creek, every agency pointed fingers at each other.

An Amador Water Agency representative wrote in an email to The Appeal and Type that the “Regional Water Quality Control Board – Division of Drinking Water would be the regulating body for a water quality emergency / contamination.”

In response to a request for comment, a representative at the Regional Water Quality Control Board wrote that, “regulatory oversight of drinking water in Amador County (location of MCSP) is done by other agencies, primarily the California State Water Resources Control Board’s Division of Drinking Water and Amador County.”

A representative with the State Water Resources Control Board told The Appeal and Type that Mule Creek prison is not a regulated public water system, and suggested that drinking water contamination at the prison would fall under the oversight of California’s Department of Public Health. (While some California prisons are connected to a broader public water system, others have their own systems, she noted.)

A California Department of Public Health representative wrote, “The California Department of Public Health does not regulate the domestic water supply at Mule Creek State Prison…Oversight of domestic drinking water and the associated distribution system downstream of the service connection to the water supplier resides with the water user (i.e. Mule Creek State Prison).”

As for Amador County’s public health department, a representative said that “the Mule Creek State Prison is under the regulatory authority of the California Valley Water Board” (which also denied regulatory oversight of drinking water).

Incarcerated people described Mule Creek as a black box with few resources, access to information, or clear paths toward remediation. Many people interviewed were not aware of the environmental lawsuits filed against Mule Creek, or the documentation around the prison’s piping failures and cross-contamination. Rumors, suspicion, and confusion about the water persist.

When Brooks goes to the doctor for his kidney cancer, he says, they always ask him, “‘Are you drinking plenty of water?’”

Whitesides, who filed the complaint in 2022, says he thinks about his lifelong illness now every time he takes a drink.

Mike Cahill, 84, gets regular CT scans following the removal of a cancerous tumor on his kidney about three years back. “I’m feeling pain in my kidney area again,” he told Type/The Appeal. He also suspects the water has something to do with it: “If you want to live, don’t drink the water.”

Incarcerated folks keep fighting

Despite the bleak outlook, many incarcerated people and their loved ones continue to file grievances and seek change.

Xavier J’Weial, who previously worked on the yard crew and now needs “chronic care” to manage persistent health issues, filed a federal lawsuit against a former Mule Creek warden alleging that drinking and bathing in the facility’s domestic water has harmed his health, violating the Eighth Amendment’s protections against cruel and unusual punishment. In April, a district judge referred the case to a dispute resolution process, during which the warden’s attorneys are meant to investigate J’Weial’s claims and try to reach a settlement. In a court filing, the warden said he was not aware of any drinking water contamination at Mule Creek.

Last summer, Dinorah Guzman posted a Change.org petition for improved water quality and regular water testing for Mule Creek State Prison after her younger brother, who is incarcerated at the prison, informed her of the drinking water quality. She also submitted concerns to CDCR representatives. Dawn Santos, a litigation coordinator for the prison, responded, “With the limited information you have provided, I completed an inquiry. No one that I contacted is aware of water bottles needing to be distributed.”

Around the same time, Mule Creek’s Inmate Advisory Council (IAC), a group of incarcerated representatives that meet with prison administration, raised concerns about drinking water on the prison’s D Yard “smelling and appearing contaminated.” According to meeting minutes, CDCR’s Healthcare Services and Plant Operations claimed they were unaware of the issue and promised to look into it. But months later, we received numerous messages about drinking water on D Yard: “The water here today is brown!!! Totally nasty,” wrote Timothy Pemberton on September 30th.

The administration acknowledged issues with the prison’s water line in an October Inmate Advisory Council meeting. The meeting minutes recorded that “a water line needed to be repaired, and the water was treated afterwards,” according to CDCR administrators. “The treatment caused the chlorine smell and cloudiness in the water for a brief time. Should there be any further issues that affect the population, Medical will let IAC know; also, Medical does regular water testing.” The issue was closed.

But the water quality concerns persist. And many in Mule Creek are forced to live with chronic illness.

For Curly Brooks, his condition is bound up with tragedies that mount so frequently inside prison they become normal. “The way I look at it, I’ve got two choices,” he said soon after his diagnosis. “Sit around and worry myself sicker dwelling on bad breaks and buzzard luck, or live every day I got left the best way I can.”

Paco Alvarez, Iqra Salah, and Jamie Jiang contributed research.