This story was supported by the Wayne Barrett Project, the Fund for Investigative Journalism, and the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

When the power cut out around 5 p.m. on a hot July weekend in 2023, Jerry Baker had one thought: “Here we go again.”

First, Baker had to inform his nearly two dozen staff: We’re in power outage mode. Several counselors zipped around the camp, assessing electric loads and determining what could be connected to the generators. Off went the pool pump and swamp coolers — except the one in the infirmary — along with the air conditioning in several cabins.

Baker is the founder of Camp Tuolumne Trails, a summer camp nestled in the Sierra foothills bordering Yosemite National Park. Each summer, it holds several sessions for dozens of adults and kids with disabilities. Usually, the outside world and its challenges seem far removed from the pine-covered campus. Campers board in log cabins equipped with power lifts and accessible bathrooms to swim, stargaze and care for the camp’s miniature donkey, Jenny. But in recent years, it’s become harder to keep certain challenges at bay.

Pacific Gas & Electric Company, the utility that provides power to the area, uses so-called “fast-trip” settings to prevent wildfire ignitions. These settings encompass a suite of technologies — including software and equipment — that can be programmed to sense physical hazards that might spark a fire. When that happens, equipment on the lines cuts off power within milliseconds. The threat of fire here is real; a camp overlook reveals scorched, rolling hills marking the scar of the Rim Fire, which burned about 400 square miles and nudged the camp’s border in 2013.

The Rim Fire runs up the Wild and Scenic Tuolumne River canyon in the community of Groveland, California, in 2013. Image: Tracy Barbutes/High Country News

Baker had already invested in a large generator that could keep essential parts of the camp running — refrigerating medicines and running the elevators and breathing machines — in case of an emergency. But it broke down, and he hadn’t yet found a mechanic to fix it.

Baker’s neighbors are also learning how to cope. That same weekend, a few miles away in downtown Groveland, Finn Horsley, who owns a local hotel and restaurant, muttered the same refrain: “Here we go again.”

Horsley filled fridges with hotel trays of ice to keep precious food from spoiling. He informed the restaurant’s diners that their meals might never come. An outage, he told guests, could last a few hours, or more than a day. That night was one of at least eight dinner services the Hotel Charlotte and its restaurant lost that year, Horsley said. But he’s equally concerned about keeping his guests — and his own family — cool and safe in the punishing summer heat. “This stuff is dangerous, never mind the inconvenience on the business,” he said.

A few doors down, at one of the oldest bars in the state, the lights cut out and two gas-powered generators kicked in. Owner Chris Loh lit the restroom with candles, and the Iron Door Saloon switched its generators between refrigerators, a power-hungry exhaust hood and the bar’s carbonation system to serve sodas and beer. “It’s basically like I’m running around doing this weird, circular electrical swap-out thing,” he said.

Back at Camp Tuolumne Trails, California’s dry July heat did not let up as the night grew dark. Baker and his staff engaged in a similar dance: alternating between powering refrigerators, freezers and air conditioning with a group of small backup generators. They had to use a tractor to move one particularly hefty generator.

“All of a sudden, I realized there was a good chance I was going to get somebody seriously hurt,” Baker said. “All of us were dead beat. At that point I said, ‘Turn off the cooler, let the food go bad, keep the campers safe.’”

For millions of Californians, these electrical gymnastics are now the norm.

A medical lift, seen in Camp Tuolumne Trails’ infirmary is dependent on electricity and must be powered by a generator when the power is out. Image: Tracy Barbutes

In fall 2018, a shower of molten metal landed near an unpaved road 150 miles north of Groveland. The resulting Camp Fire burned for more than two weeks, consuming nearly 19,000 structures and practically the entire town of Paradise. Eighty-five Californians died, making it the deadliest fire in state history. An investigation linked the initial spark to a damaged transmission tower owned by PG&E, which provides electricity to 5.6 million customers throughout much of Northern and Central California.

In the wake of the fire, thousands of Californians sued the utility, one of the nation’s largest, for damages. Faced with the prospect of massive liabilities from the Camp Fire and previous wildfires, PG&E filed for bankruptcy, its second in less than two decades.

California policymakers and regulators responded aggressively, establishing advisory committees and councils and passing laws designed to reduce wildfire risk from the state’s aging electrical infrastructure. PG&E, too, took serious action: adding hundreds of weather stations to provide real-time data, clearing trees near utility lines, and making plans to bury thousands of miles of power lines in the ground, so they can’t spark fires.

But as climate change intensifies wildfire risk, the fire-prevention strategy most familiar to many Californians has become the frequent power outages that cut electricity thousands of times every year.

Image: Parker Ziegler/High Country News

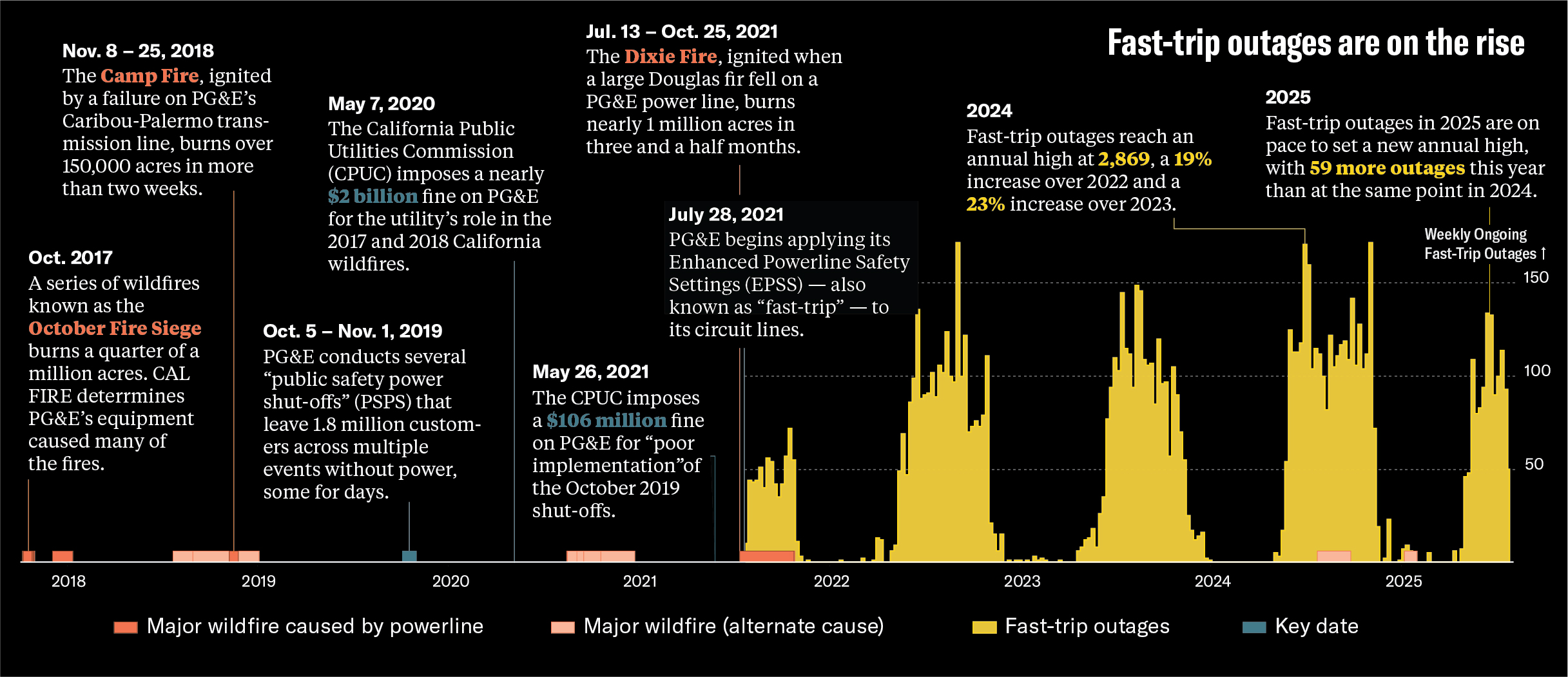

PG&E has used scheduled preemptive power outages regularly since 2019, but the company began to use extra-sensitive fast-trip settings in the summer of 2021. PG&E launched the settings soon after a tree branch hit one of the utility’s lines, igniting the Dixie Fire, which still ranks as the second-largest in California history. Now, with fast-trip settings, tree branches swaying in the wind, squirrels gnawing on lines, even a glitch in PG&E’s software could shut down power lines in milliseconds. The utility now uses these settings on about 40% of its distribution lines, which ferry electricity from the grid to homes and businesses. The unplanned blackouts regularly impact hospitals, schools and people who rely on oxygen, CPAP machines and other medical equipment. They can last a few minutes, or stretch on for hours. And because they are designed to be instantaneous, residents never know when they will happen.

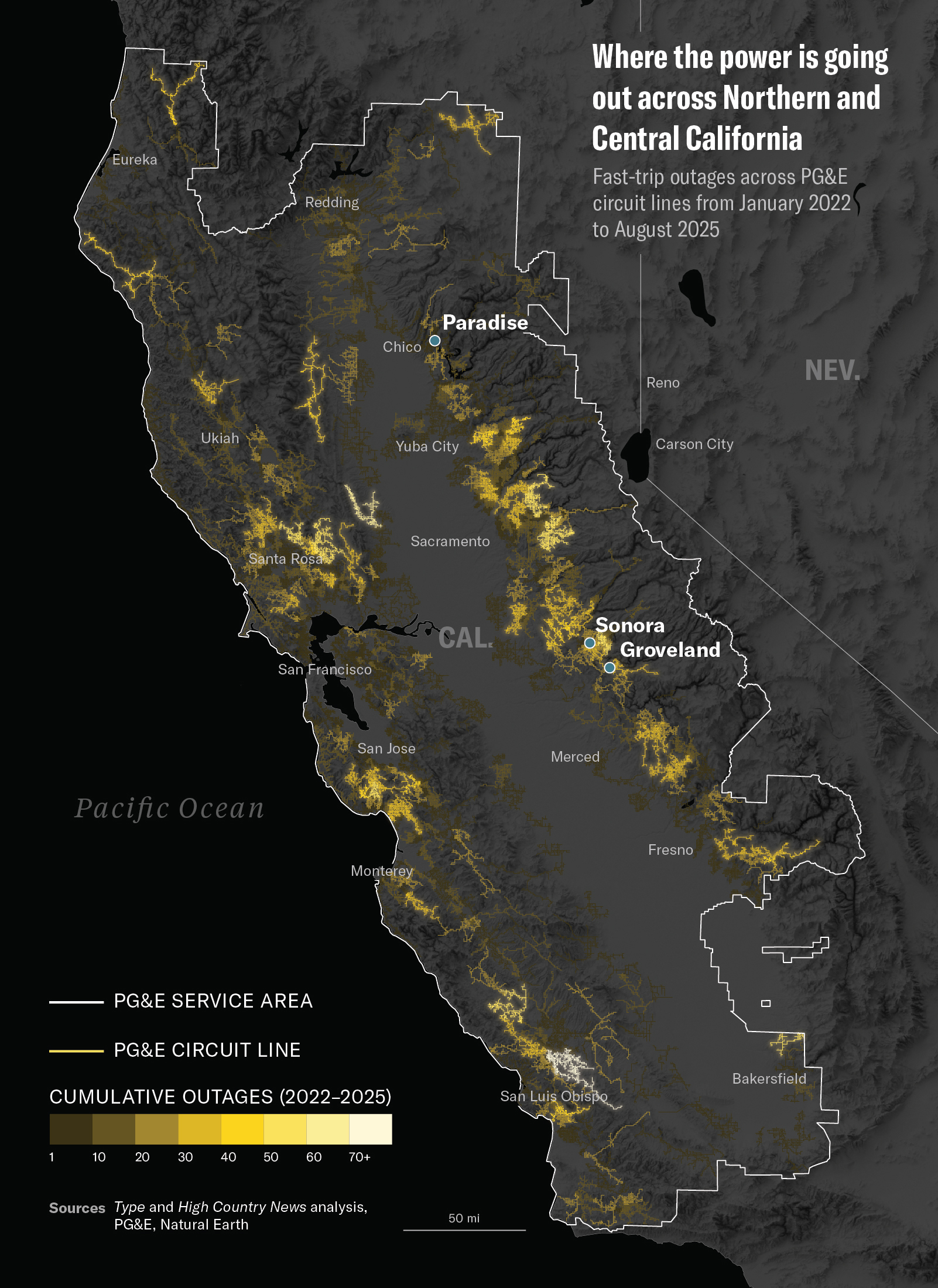

The two segments of the grid, called circuit lines, that service Groveland are some of the least reliable in PG&E’s territory, based on the number of fast-trip outages they endure each year. And though the area has exceptionally poor performance, its situation is not unique. Over time, PG&E has slightly reduced how long fast-trip outages last on average, but the outages have increased in number — growing about 20% from 2022 to 2024 — and in how many people they impact.

In 2024, nearly a million customers experienced fast-trip outages, many of them repeatedly. More customers experienced outages in 2024 than in any other year of the program.

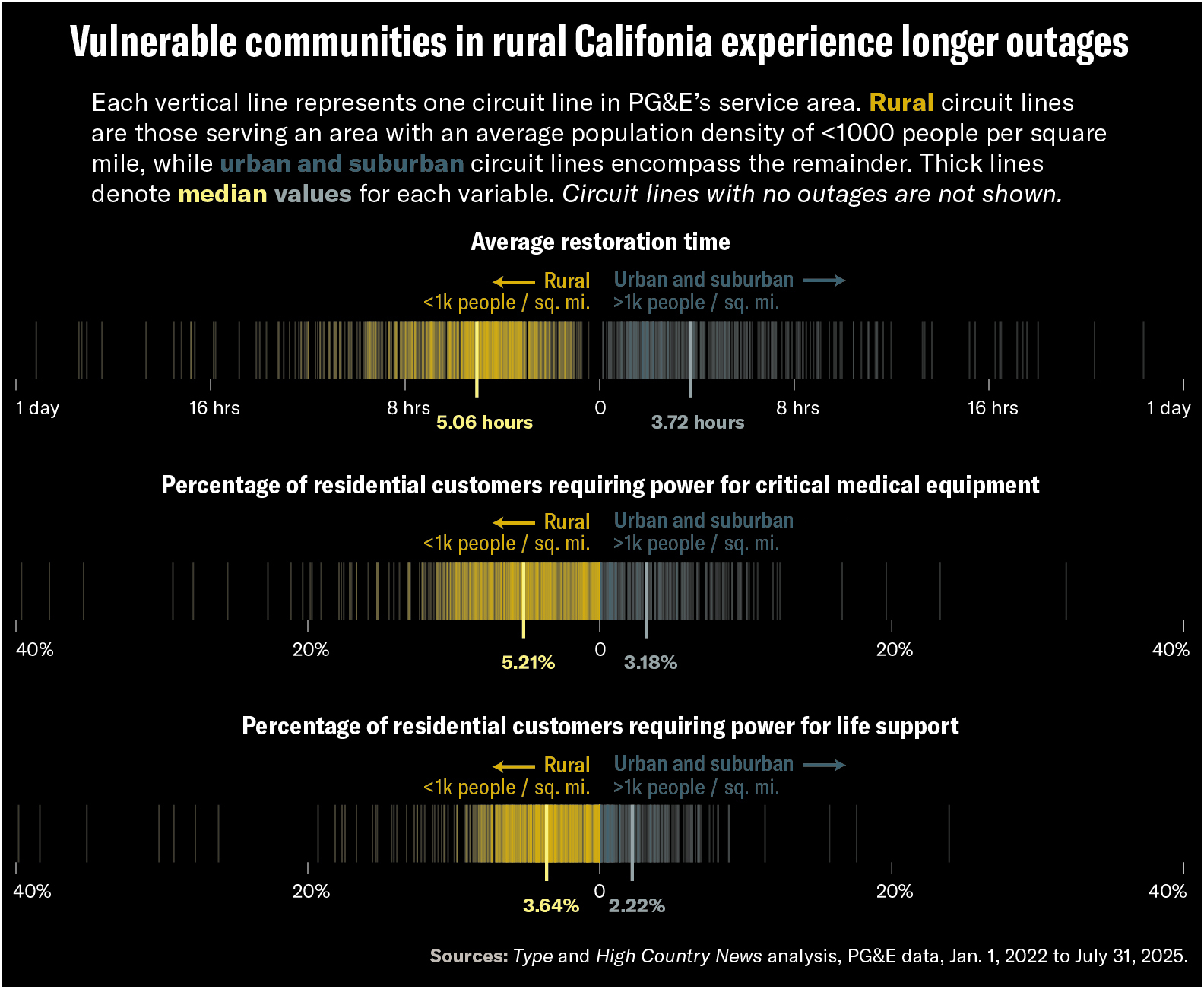

The outages predominantly occur in rural areas, based on a first-of-its-kind analysis of publicly accessible utility data from Type and High Country News. Rural communities — which often border forests and face heightened wildfire risk — experience 600% more fast-trip outages than urban and suburban areas. These outages also tend to last longer. That means that the worst impacts from fast-trip outages occur in remote areas — exactly where residents tend to be the most vulnerable due to age, disability or their distance from essential services like hospitals. And these outages are becoming more frequent.

Image: Parker Ziegler/High Country News

Outages have increased in part due to more dangerous fire conditions, Brienden Realph, the utility’s director of enhanced power-line safety settings, said. In an email, PG&E spokesperson Andria Borba noted that 2024 was an exceptionally hot, dry summer, necessitating the use of fast-trip to prevent wildfires from starting.

Borba also said there has been a “significant increase” in the number of devices with fast-trip settings. However, a recent report from PG&E suggests that the increase doesn’t fully account for the rise in outages; outages increased overall between 2022 and 2024, even when normalized for the number of days in which fast-trip settings were active.

Even as they recognize the extreme risk of fire, some rural residents have grown frustrated with the frequent interruptions and feel skeptical of PG&E’s motives. “They’re shutting the power off so that they don’t start a fire with their bad equipment and then get sued,” Willow Polson, who has lived in Groveland for more than 25 years, said. “They’re throwing us rural residents under the bus, for their safety more than our safety.”

In an email, Borba said the utility “understand(s) the burden and inconvenience not having electricity creates for our customers” and added that PG&E works every day to refine fast-trip settings “to prevent an ignition and minimize reliability concerns for our customers.”

California is not alone in facing these challenges; utilities in wildfire-prone Western states like Utah, Colorado and Oregon have implemented similar outage technology. These companies face a dilemma: Utilities increasingly face blowback when they turn the power off proactively, as in Northern California, as well as when they do not, as happened after the devastating fires in Los Angeles and Lahaina, Hawai’i. Utilities also face hugely expensive liabilities if a fire ignites as a result of their equipment.

Utilities and those who govern them must decide how much fire risk can be mitigated, how much to spend on these efforts, and what kind of sacrifices — including reliable electricity — customers will tolerate.

Few Californians would say that all power outages can be avoided; fast-trip outages have prevented fires and likely saved lives. PG&E says the settings reduced ignitions by 65% in 2024. Independent analysis of data from 2022 and 2023 by researchers at University of California, Berkeley puts that figure even higher — at an average of 82% — where fast-trip is used. According to Borba, every time a fast-trip outage occurs, it’s “one time when we’re keeping the community safe from the threat of wildfire.”

But it’s unclear whether every fast-trip outage is triggered by an active fire risk. According to data PG&E submits to regulators, the company doesn’t understand why many of these outages happen. Between 2022 to 2024, the most common cause of fast-trip outages was listed as “unknown,” representing about 40% of outages. Realph said the utility takes unknown outages “very seriously” and investigates each one in an effort to determine what caused it, adding that PG&E is on track to reduce the proportion of unknown outages in 2025 to about 34% of all fast-trip outages.

Notably, the number of “company-initiated” fast-trip outages — which can be triggered by software glitches, accidents during maintenance and construction, or anything else directly caused by PG&E — jumped from 4% in 2022 to 13% in 2024. Borba said that during the initial implementation of fast-trip, some settings were overly sensitive and needed to be adjusted. Realph said the company has recently improved an algorithm that was causing some of these outages and hopes to see a reduction.

As the utility fine-tunes its system, residents are left with limited options. PG&E has argued that the outages must continue due to climate change and dire wildfire conditions. Legislators have not passed any laws requiring changes to how utilities implement automatic power shut-offs. And regulators have not required PG&E to reduce fast-trip outages, despite public outcry.

In the absence of external support, both residents and local governments say they have had to shoulder the costs, investing tens of thousands of dollars in backup generators, tossing hundreds of dollars’ worth of spoiled food, and employing scarce resources to direct traffic or set up community cooling centers. Residents can ask the utility to reimburse them for some of these costs, but losses must be a result of negligence by PG&E.

Some residents believe PG&E has sacrificed its reliability — one of a utility’s primary mandates — not just to prevent wildfires, but also to protect its own financial interest.

“They really aren’t suffering on any corporate level from these problems,” Baker, the camp founder, said. “The suffering is all being done by their customers.”

Deborah Karr stores her two utility-distributed batteries, each weighing nearly 70 pounds, in the hallway closet of her modest one-bedroom apartment, where her splatter art covers the walls, and a Christmas tree lights up a corner of the living room in late October. She is one of the roughly 28,000 PG&E customers to receive a free-standing backup battery over the last five years; Karr uses a CPAP machine at night and needs electricity to run it.

The electricity lines serving Blackberry Oaks, the low-income senior housing building in the Sierra foothills where Karr has lived for the last six years, has lost power 19 times due to fast-trip outages between 2023 and 2024. When that happens, Karr often heads down the hall to her neighbor Barbara North’s doily-covered apartment to play gin rummy until light returns.

Everything in the complex’s 42 units runs on electricity. In a building where much of the population is elderly or disabled, blackouts can cause fear and chaos. Residents get stuck in the elevator; those in wheelchairs sit stranded on certain floors.

North, who is in her 80s, suffers from lung disease and congestive heart failure. When the electricity cuts out, her oxygen pump’s alarm alerts her that it’s no longer running; during middle-of-the-night outages, it jolts her awake. She too has a free battery, which she keeps in her bedroom, but it’s too small to support her oxygen machine. Without electricity, she is forced to connect to large compressed oxygen tanks that only last eight hours at a time.

“When my electricity goes off, I’m in a mess,” she said from a leather easy chair in her living room. Backup batteries help, North said, but they don’t last indefinitely. “When that runs out, you’re really — excuse my expression — screwed.”

The vulnerability of people who might suffer from a sudden blackout is exacerbated in communities like the one where Blackberry Oaks is located. Along circuit lines in rural areas, there are higher rates of people with no internet or phone service in their homes, and 10% more people with disabilities than in urban areas.

Those disparities are even more dramatic in Groveland, where 23% of the people along the circuit lines live with a disability, according to census data. That’s more than double the rate in more densely populated parts of California. In 2024, fast-trip power outages cut electricity for more than 2,200 Groveland customers who need electricity for medical devices or life-support equipment, such as respirators or motorized wheelchairs, according to PG&E data.

Across PG&E’s entire service area, 233,590 customers rely on electricity for medical devices or life support, Borba said. And while the utility does not share the number of unique customers impacted by each outage, Type and High Country News’ analysis of publicly accessible information estimates that more than 20,000 of these customers live along circuits with 10 or more outages each year. All of these vulnerable customers are in rural areas. In 2024, more than 48,000 people who required electricity for medical needs endured fast-trip outages. Outages also impacted thousands of customers who use well water in 2024. During an outage, those people may lose access to running water.

PG&E does offer some programs to help medically vulnerable people cope with outages, but it’s unclear if they are reaching everyone who needs help. PG&E distributes backup batteries and other equipment like insulin coolers and mini fridges. The utility works with organizations to contact eligible customers and certain medically vulnerable customers can also reach out to receive that equipment. The utility has distributed roughly 28,000 free-standing batteries and nearly 1,900 permanently-installed backup batteries. Since 2020, nearly 34,000 PG&E customers have applied for batteries, according to the utility. The utility doesn’t “make different accommodations for medical needs customers,” Borba said in an email, but encourages customers to develop personalized safety plans, with resources provided on the PG&E website.

The utility also offers rebates of a few hundred dollars for customers to purchase batteries or generators — though the customers must pay to fuel them, and the systems can cost thousands of dollars to purchase outright. The rebates are open to people who live in high fire-threat areas or are served by power lines with fast-trip settings, but it’s up to customers to apply for them.

PG&E also has bigger system upgrades in the works, including projects to bury or insulate thousands of miles of power lines around the state to keep them from sparking. Meanwhile, it has not set any public targets to reduce or end the fast-trip outages.

“We want to encourage wildfire risk-reduction measures,” said John Kennedy, a senior policy advocate at Rural County Representatives of California, a membership coalition that advocates for the state’s rural counties. “But you should be making progress on the back end, and we’re not quite sure what that progress is.”

California first authorized the use of “Public Safety Power Shut-offs” — preemptive scheduled power outages to avoid wildfires on hot dry days with strong winds — for one utility more than a decade ago, and later extended the authorization to all investor-owned utilities. But those companies aggressively expanded their use after the 2018 Camp Fire. In October 2019, about nine months after PG&E filed for bankruptcy due to wildfire-related costs, the utility shut off electricity for about 1.8 million customers across multiple events. Some people endured blackouts that lasted days. The two largest outages impacted more customers than any other public safety power shut-off in California before or since.

Pushback was swift. “Sadly, the state has learned too well in recent years the level of destruction climate-change-induced weather events can have on our communities when combined with negligent maintenance of electrical infrastructure,” Marybel Batjer, then-president of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), said in an emergency meeting in 2019 to discuss the outages. “But resilience will not and should never translate to Californians being willing to put up with inadequate execution of measures that are supposed to keep them safe.”

CPUC, which regulates the state’s investor-owned electric utilities, fined PG&E $106 million in 2021 for what it called “poor implementation” of power outages, noting the company’s failure to provide accurate outage information online and notify customers in advance, among other violations.

The event further soured public sentiment on PG&E, but financially, the fines paled in comparison to the fire-related liabilities the utility was facing as part of its bankruptcy. When the utility announced its reorganization plan in mid-2020, it accounted for $13.5 billion in payments to fire victims, plus billions more for insurers and cities and counties. CPUC slapped PG&E with a $2 billion fine for its role in the 2017 and 2018 fires. And shortly before the company filed for bankruptcy, rating agencies downgraded its credit to “junk” status, potentially impacting its ability to access the capital that’s essential for utility operations.

Determined to avoid another destructive fire, the company reasoned that power outages were an unfortunate necessity.

“Let me assure you, we do not like to turn off the power. It runs contrary to the reason any of us ever got in this business,” then-PG&E president and CEO Bill Johnson said at that emergency meeting in 2019. “The fact is that we did this for one reason, and that is safety.”

My business is having to take on the burdens of PG&E not being able to provide a safe, reliable power grid that doesn’t cause wildfires to burn down towns.

Finn Horsley, Owner, Hotel Charlotte

In 2021, the company introduced automatic fast-trip outages. Fast-trip outages, on average, are much shorter than scheduled shut-offs, but they can also last for long periods without notice. Between 2022 and July 2025, the utility executed just 12 preemptive power outages, while the number of fast-trip outages exceeded 8,600.

Because fast-trip outages happen automatically, the CPUC says they cannot be regulated in the same way as preemptive shutoffs. Though the commission created rules for the implementation of scheduled outages, it has not done the same for fast-trip. Every year, investor-owned utilities must outline a plan for preemptive outages to regulators, including information on how they will provide enhanced support to vulnerable customers and set up community resource centers for residents to access electricity and get updates. Those same plans are not required for fast-trip outages. PG&E has faced millions of dollars in penalties for improperly handling preemptive power shut-offs, but the utility has not suffered any regulatory fines for its implementation of fast-trip.

In recent years, PG&E has also requested regulatory approval to spend billions of dollars rehabilitating its system to make it more resilient and less likely to ignite costly and dangerous wildfires. After its bankruptcy, the utility embarked on a mission to bury thousands of miles of lines and insulate thousands more miles, installing equipment called “covered conductors.” From the utility’s perspective, burying power lines is “the best tool in the highest-fire risk areas,” because it reduces wildfire risk by 98%. But it is also expensive, at about $3 million per mile, and it will take years to underground a significant portion of the grid.

There is still debate over the best solutions for keeping PG&E’s aging grid, which winds through some of California’s highest fire-risk areas, from sparking. Some consumer advocates prefer short-term power outages paired with insulated lines, which are cheaper and faster to install than underground lines, and, they argue, provide adequate risk protection. Research from UC Berkeley contends that fast-trip outages can cost-effectively produce the same risk reduction as undergrounding lines, even when controlling for the costs of outages to customers — including those who use electricity for medical devices.

No matter the strategy, it’s residents who will pay for the majority of it. When a regulated utility builds and installs new equipment, it earns a guaranteed return on that investment, which is embedded into the rates it collects. A recently passed California law does not allow the state’s largest utilities to collect that return on the first $6 billion the companies spend cumulatively on wildfire mitigation after 2025, but customers are slated to pay much more than that. California has also created a fund to help utilities pay for wildfire liabilities, but its available funds are much less than the amount that utilities would likely need to pay if a large fire ignites.

That financial structure leaves California customers — particularly in rural areas — with less reliability along with exceedingly high electricity rates, as well as the personal costs many of them pay to cope with outages. Because PG&E plans to continue using fast-trip for years while it buries lines and replaces other equipment, there is no clear end in sight. The outages cost the utility little in the short term, while its undergrounding plans set it up for years of regulator-approved financial returns.

Image: Parker Ziegler/High Country News

In response to questions about whether regulators have taken any action to reduce PG&E’s use of fast-trip outages, a CPUC spokesperson said the commission has not implemented any fast-trip fines or penalties, but it meets regularly with PG&E to discuss how to reduce the duration and scope of fast-trip outages. The commission has also started a public policy process to address reliability issues, including those caused by fast-trip.

Above all, PG&E said, it aims to prevent ignitions. “We just don’t want to have an outage, but really I don’t want to have an ignition,” Realph said. “We’re going to do everything we can to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

PG&E’s overall reliability has suffered due to these power outages. In an annual report on its reliability, PG&E notes that its performance declined between 2022 and 2024. Fast-trip settings are the largest contributor to interruptions on its system by far, according to the report.

“The grid is completely unreliable,” Groveland’s Horsley said. “My business is having to take on the burdens of PG&E not being able to provide a safe, reliable power grid that doesn’t cause wildfires to burn down towns.”

As the company’s reliability has faltered, its residential customers’ electric rates have climbed, increasing over 100% during the last decade. California has the second-highest residential electricity rates in the country. “That’s just salt in the wound,” Horsley said.

Hotel Charlotte owner, Finn Horsley, stands in the front of his business, located on Main Street in Groveland, California, Friday, October 3, 2025.

For High Country News Image: Tracy Barbutes

Continuing to raise rates to fund additional wildfire-prevention programs is becoming increasingly infeasible because California customers already pay so much, said Michael Wara, who directs the Climate and Energy Policy Program at Stanford University. Nearly a quarter of the revenue that PG&E now collects from its customers goes toward wildfire mitigation. Costs are expected to continue rising as climate change makes wildfires more likely and more dangerous, and customers have to pay for more measures to avoid them. And rates fund more than wildfire-related improvements; California is also in the midst of a costly endeavor to decarbonize its grid, and putting more money toward wildfire mitigation could undercut those efforts.

Already, one in five California households struggle to pay their electric bill. As of July, well over 1 million PG&E customers were behind on payments.

“The rates have gone up so high that most of the people who are on Social Security can’t afford to pay their electric bill,” Karr, of Blackberry Oaks, said. She previously worked at a community service center that provides food, clothing and other support, including helping people navigate their utility bills.

On top of the rising rates, many Groveland residents have sunk thousands of dollars into generators. Polson said she has gone “deeply into debt” to buy two generators for her house.

And those systems remain inaccessible to many. At a weekly crafts circle held at a local community center for older adults, attendees, many of them retired, said the financial divide is clear.

“We keep debating, ‘Do we want to spend the 10 grand?’” Donna Johnson said as she knitted a hat to donate to a local cancer unit.

“How’re you going to do that if you’re on a fixed income?” Kelly Sexton, an attendee working on crowns for the annual Advent event, asked.

“You don’t,” Johnson said. “Tuolumne County is poor.”

Businesses in Groveland, which largely line one of the main arteries that empties into Yosemite National Park, have also suffered. Loh and Horsley earn the great majority of their profits in the summer, when fire risk is high. During the July Fourth weekend of 2023, Loh said his Iron Door Saloon lost at least $60,000 from the fast-trip outages. By Horsley’s account, his business has lost tens of thousands of dollars due to canceled reservations and refunds, missed dinner service, spoiled food and other expenses.

“This cannot be the solution,” Horsley said. “Don’t make me pay for your problems.”

The Yosemite gateway community of Groveland, California, has been without power since yesterday afternoon, and many local businesses, including Hotel Charlotte, are closed due to a PG&E Public Safety Power Shutoff (PSPS), October 10, 2019. Image: Tracy Barbutes

Local governments say they’ve suffered, too. Last year, during an outage that coincided with a heat wave, Sonoma County set up a cooling center where people could sit in air-conditioned spaces and use charging stations, because PG&E did not. “PG&E continues to externalize the responsibility and costs of keeping its customers safe during wildfire-mitigation outages,” lawyers for the county wrote in a 2024 regulatory document. “Fast-trip is not a benign outage program, and PG&E has yet to prove that the scope and scale of fast-trip is appropriately calibrated.”

Borba, the PG&E spokesperson, said the utility only sets up those Community Resource Centers during planned outages. The unplanned nature of fast-trip outages, she said, makes it challenging to make such facilities available.

Over time, system hardening projects like undergrounding and insulating lines should reduce the need for fast-trip outages, a CPUC spokesperson said, particularly in rural areas. “The way to restrict these outages is through investment in infrastructure such as covered conductor or undergrounding, or increased vegetation management, which all of the utilities are pursuing at an increased rate,” spokesperson Terrie Prosper wrote in an email.

But the data on these projects so far shows mixed — if any — results in reducing outage impacts. Type and High Country News analyzed publicly accessible data on PG&E system hardening projects, although it is unclear if the public-facing data includes all the company’s projects.

A review of the circuit lines where system hardening projects were completed in 2022 or earlier shows that 37% of the lines saw a decrease in fast-trip outages, but 51% saw outage frequency go up. And data on PG&E’s vegetation management program, which involves cutting trees and branches near electric lines, is limited: Of the 136 projects they have listed, only five are completed.

For those watching such efforts unfold, progress on improving outage trends can appear opaque.

PG&E is “not providing any real feedback on what they’re doing to evaluate high-frequency outage circuits and the measures they’re taking to reduce the number of outages on those circuits,” Kennedy at Rural County Representatives of California said. “As we’re seeing improvements in the system, we should see fewer instances in which things come in contact with the power line” and cause outages.

For Baker, that terrifying night at camp in 2023 left its mark. At one point, he tasked a staffer, equipped with a walkie-talkie and a handheld thermometer, to monitor temperature fluctuations in one cabin in order to determine when the air conditioning could be turned off while ensuring the campers stayed cool. Around then, Baker told his staffers to give up on the refrigerators. “Four o’clock came along, and it was obvious that we were just out of control,” he said. “We were not going to be able to make this work.”

Around 5 in the morning, Baker drove nearly 70 miles in the camp SUV to a store renting generators, arriving right as the doors opened.

The generator he rented sat at the camp for six weeks. Whenever someone used the elevator, Baker switched that load from the electric grid to the generator in case the power was cut while the elevator was in use. The machine cost about $800 a week to run. “It wasn’t cheap, but it was a bargain compared to getting people stuck,” he said. “Three-fourths of the time I never turned it on, but I was afraid not to have it.”

“You have no way of predicting what the next crisis is going to be,” he added.

In the last couple of years, the camp has received a donated generator that can power most of the property. But the camp still needs to pay the “extraordinarily expensive” amount it costs to keep it fueled, on top of its PG&E bill.

Baker said the outages in his area seem to be improving, but he’s not sure how much of this is “blind luck” versus changing priorities and policies. Horsley, too, said PG&E was doing a better job in Groveland.

But that is not the case in all rural areas: PG&E logged more fast-trip outages in 2024, and outages impacted more customers than in any other year since the program began. In the areas where those outages occur most often, they last the longest.

“Am I glad that we’re worried about the impact of fires? Hell, yes,” Baker said. “However, I don’t really feel like we are getting to the root cause at all.”

Camp Tuolumne Trails and the Wild and Scenic Tuolumne River canyon in Groveland, California. Image: Tracy Barbutes

Ethan Corey contributed research.