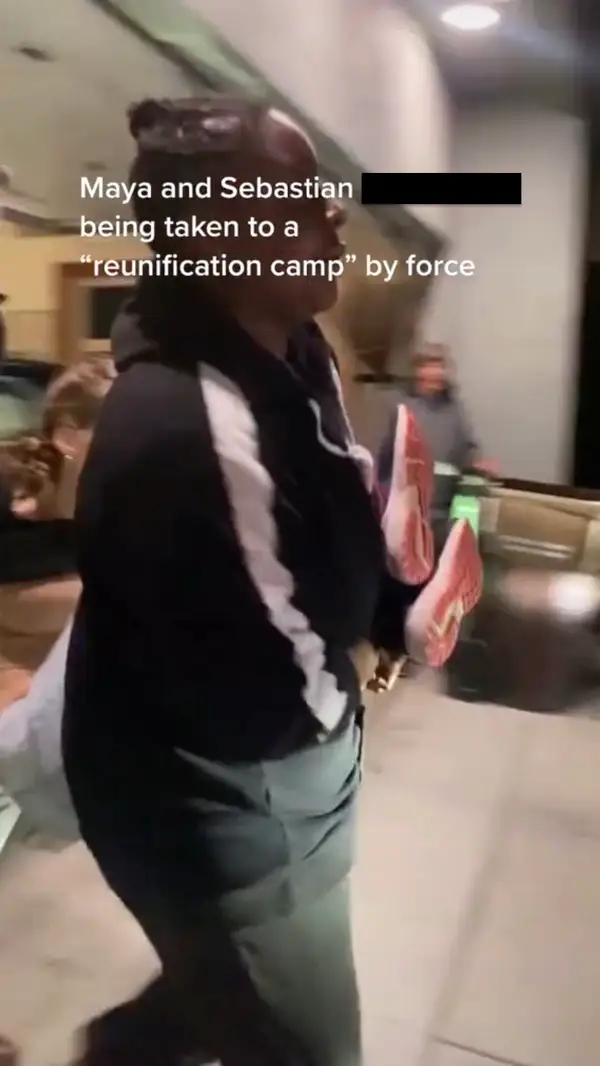

A video that went viral on TikTok last fall showed 15-year-old Maya and 11-year-old Sebastian, siblings from Santa Cruz, California, pleading and screaming in protest as three strangers cornered them in a garage, picked them up, and forced them into a black SUV. “You’re kidnapping me!” Maya cried as she struggled in vain to get away.

But this wasn’t an illegal kidnapping. In fact, it had been ordered by a judge.

Hours earlier, a family court judge had put Maya and Sebastian in the sole custody of their mother, even though they’d both accused her of abuse and wanted to stay with their father. The judge had also ordered the children into a treatment program for “parental alienation” and authorized an intervention company to take them there.

The video was viewed millions of times and ignited a national movement to support Maya, Sebastian, and other children who’ve been forced into the custody of a parent they’ve accused of abuse. But Maya and Sebastian essentially vanished that night. They never returned to their schools in Santa Cruz, and friends and family didn’t know where they were.

The children weren’t heard from publicly for seven months — until Monday morning, when they emerged in an online video announcing that they’d run away from their mom. And in an exclusive interview with Insider and Type Investigations that took place while they were still living with their mother, the children described everything that happened after they were seized.

Maya and Sebastian’s ordeal began on October 20, 2022, when California Superior Court Judge Rebecca Connolly ordered them into the custody of their estranged mother, Jessica, and into a reunification program called One Family at a Time. The program is grounded in the theory of parental alienation, which was developed in the 1980s by the psychiatrist Dr. Richard Gardner, who thought that divorcing mothers often brainwash children into falsely accusing their fathers of abuse. In severe cases, Gardner wrote, children suffering from “parental alienation syndrome” must be cut off from the parent they prefer, transferred to the care of the parent they claim to fear, and subjected to “threat therapy.”

Lynn Steinberg, a family therapist in Los Angeles, runs the reunification program One Family at a Time. She says children who aren’t reunited with an alienated parent risk being plagued by guilt. Image: Still from a forthcoming documentary by Insider/Retro Report/Type Investigations

Parental alienation has never been accepted as a psychiatric disorder by the medical establishment. Yet today, mental-health providers across the United States purport to treat it, usually under an order from a judge. Recently, a collaborative investigation by Insider and Type found that since 2000, judges have sent more than 600 children to reunification programs that recommend the temporary exile of their trusted parent. One such program is One Family at a Time, which is run by therapist Lynn Steinberg, who says it has treated 50 families over the past eight years.

Ruling from the bench last October, Connolly said that while Maya and Sebastian had accused Jessica of abuse, and Maya had testified to this alleged abuse, the children’s statements were “ever-changing” and not credible. Instead, Connolly blamed the children’s rejection of their mother on their father, Justin, who’d divorced Jessica in 2019. (Insider is identifying members of the family by their first names only to protect the privacy of minors.) Connolly barred Justin and everyone associated with him from contact with the children for at least 90 days. The children were to travel immediately to Steinberg’s office in Los Angeles, where they would undergo a four-day workshop with Jessica.

Immediately after the workshop, Jessica said in a court filing that her relationship with the children had “utterly changed for the better.” Likewise, in an interview with Insider and Type in April, Steinberg described the family’s workshop as a success. Steinberg said that virtually all the children her program enrolls have falsely accused a parent of abuse and that she does not accept children into her program whose abuse claims have been substantiated. While Maya “hung onto” her belief that she’d been abused for longer than most children would, Steinberg said, Maya eventually apologized to Jessica, and both children sat on their mother’s lap and cried.

“And they were just re-bonding with their mom — a mom that they probably desperately wanted to see, desperately wanted to be close to,” Steinberg said.

Image: TikTok

But on Monday, Maya and Sebastian, now 16 and 12, announced in a video posted by an activist that they had fled their mother, who had moved them to Olympia, Washington. In a phone interview that took place before they left, both children said they stood by their allegations and were complying with Steinberg’s program and with their mother out of fear. They said they wanted to return to Santa Cruz and to their father, whom they hadn’t seen since October, and that they wanted their story told.

“I don’t ever want to live with my mom or see my mom again,” Maya said. “I’m scared of her. I want to be with my dad and with my dad’s family. And what happened was not OK.”

The children didn’t disclose their location in the video. But later in the week, they posted eight videos to Maya’s Instagram account. In one, Maya says she and her brother are safe and thanks “all the people in Santa Cruz who made it possible for us to get away and motivated us to get out of there.”

In court testimony last October, Jessica denied abusing the children. Last summer, an investigation into some of the children’s allegations by the Santa Cruz County child welfare agency was “inconclusive,” court records show. The Santa Cruz Police Department also investigated Jessica last summer and filed no charges, according to court records.

An email sent to Jessica was answered by her attorney Heidi Simonson, who said that state law enforcement and the FBI were investigating the “criminal act of luring the children away, and concealing them from their custodial parent.” Simonson defended parental alienation but declined to answer written questions, citing a gag order imposed by Connolly.

Though Steinberg spoke with Insider and Type at length earlier this year, she didn’t respond to a request for another interview this week, nor to a list of questions.

Justin said he’d seen the initial video posted on Monday and was praying that the children were safe, but other than that, he couldn’t comment.

In the phone interview and in one of her new Instagram videos, Maya said that both she and Sebastian cried the whole way to Los Angeles after being seized by agents from Assisted Interventions. At first, Maya said, the transporters pinned her to the car floor in a “full body lock.” She said her back hurt and her lip was bleeding. Assisted Interventions didn’t reply to requests for comment.

When they arrived at Steinberg’s office, Maya started hyperventilating with fear, she said, partly because she knew her mother would be joining them. But Steinberg told Maya to “stop pretending,” she said.

In her April interview, Steinberg said she doesn’t use coercion or threats. But Maya said that when she and Sebastian raised their abuse allegations with Steinberg and a clinician who was assisting her, the psychologist Regina Marshall, the therapists called them liars and threatened them. Maya said they were told that if they didn’t start telling the truth, they’d have to go “somewhere else” where necessities like blankets and food could be withheld. Maya said they were also warned that they could be separated from each other and kept from their father for years.

Their mother was present for this discussion but didn’t say much, Maya said. Marshall, who is based in Monterey, California, and was appointed by the court in 2021 to help the children reconcile with Jessica, declined to answer written questions. In an email, Marshall said that for legal and ethical reasons, she can’t disclose who her patients are.

Despite the pressure, Maya said, she and Sebastian never recanted. But seeing no other option, they agreed to try to get along with their mother. The children said they did show her physical affection, as Steinberg claimed, but only because Steinberg demanded it. And they said they only cried because they were scared.

For the remainder of the workshop, Maya said, Steinberg and Marshall focused on how the children had hurt their mom, how pathological this behavior was, and how they could make amends. The clinicians tried to get the children to blame their father, Maya said, but they refused.

Maya was 12 and Sebastian was 8 when their parents divorced. The parents shared custody, but the children soon began resisting their time with Jessica, court records show. In filings in late 2020 and early 2021, Justin said this was because the children didn’t feel safe at Jessica’s, while Jessica blamed Justin and his new wife, saying the children were “hewing to what they have been told (or threatened) to do or not do.” In the fall of 2021, Jessica told the court that Justin had “successfully alienated” the children from her.

Jessica’s alienation claim was eventually buttressed by Marshall, who filed a report with Connolly last September criticizing Justin for supporting the children’s abuse allegations. Saying that Justin may be “delusional,” Marshall urged immediate action. “In the larger scheme of things,” she wrote, “there is precious little time left to intervene with these children to help them heal and give them the best chance at a psychologically healthy life.”

A few weeks later, Connolly granted Jessica sole custody and ordered the children into Steinberg’s program. A request for comment from Connolly was answered by a Santa Cruz County court administrator, who said judges couldn’t discuss “pending and active” cases.

Throughout the workshop, Maya said, she and Sebastian stayed at a condo with their mother and Marshall. For costs related to the workshop, Marshall billed the family more than $10,000, while Steinberg charged more than $13,000, court records show. Assisted Interventions, which transported and monitored the children for seven days, charged more than $33,000. By court order, Justin was responsible for these costs.

Once the children were settled in Olympia with Jessica, they continued to superficially comply, they said. But at one point, Maya told her court-appointed attorney that she wanted an opportunity to testify, she said. After Jessica learned this, she brought the children to Steinberg again, Maya said. Steinberg was angry, Maya said, saying she shouldn’t be communicating with her lawyer without permission and that she couldn’t testify.

Steinberg also told Insider and Type that the incident sparked a return visit to her office. It was inappropriate, she said, for Maya to seek to speak to the judge. “What children do is they talk to their parents about what they want to do, and get permission from their parents,” Steinberg said.

Marshall and Steinberg are working to oppose Piqui’s Law, a California bill that would bar state judges from ordering children into treatments that cut them off from the parent they prefer. An attenuated version of the legislation has passed the state senate and is being weighed by the assembly, where the bill’s proponents are hoping to strengthen it. A similar law was signed by Colorado’s governor last week.

In a video she made last October, two days before the court order, Maya expressed support for Piqui’s Law. For now, however, her focus is more immediate.

“I haven’t been able to talk to my friends or my grandparents or my stepsiblings or my dad or my stepmom or any of those people who are actually supportive family in like seven months now,” she said. The adults she is allowed to speak with haven’t helped, she said. “We’ve been telling them that our highest priority is talking to those people and being around those people and being back with those people. And they’re like, ‘No, no, no.'”