On a weekday morning in early June, Ruben Garcia arrived at the Casa Oscar Romero building leased by Annunciation House, the hospitality center that he founded and that has served the indigent and immigrant community in El Paso, Texas, since 1978. He wore a striped button-down shirt and wire-rimmed glasses, his disheveled white hair loosely tumbling to one side. Garcia was orchestrating logistics for roughly 800 migrants arriving into the region that day. He received no government salary for this work. He was not doing it at the direction of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the $9 billion agency charged with detaining and transporting migrants. He was taking responsibility for these desperate and poor asylum-seekers because no one else would.

For several months spanning the spring and summer, volunteers such as Garcia made up an unheralded network of care ensuring basic safeguards—food, security, and transportation—for migrants caught up in a cynically manufactured crisis at America’s southern border. As the Trump White House pushed an image of chaos and lawlessness wrought by families in search of asylum, people in cities like El Paso offered support to those families. Some of those at the heart of this volunteer network, including the area’s congressional representative, worry that the White House’s campaign may have been a contributing motive for an alt-right fanatic who in August killed 22 people at a local Walmart in El Paso patronized by the city’s immigrant community.

Emails among El Paso officials from March show that they deferred to Annunciation House’s capacities in discussions with ICE about where to send migrants who had been recently detained at the border as part of President Trump’s crackdown on immigration. Throughout the summer, Garcia, a Jesuit-trained volunteer in his 70s, advised ICE agents on a daily basis where to send hundreds of migrant families among 30 hospitality centers—churches, nonprofits, community- and city-run shelters, and more—throughout far west Texas and southeastern New Mexico and beyond.

Only a few months earlier, Garcia said, he had relied on ICE agents to transport migrants with pending asylum cases to these centers. Upon their arrival, they would be fed and housed until they could make more long-term arrangements as they awaited their court dates. But in March, the authority to release asylum-seekers abruptly transferred to U.S. Border Patrol, which refused to deliver them to these orderly respite centers. Instead, the agency started releasing thousands of people, often with just the clothes on their backs and no means of contacting friends or family, into city streets across New Mexico, Texas, Arizona, and California.

One of those places was rural Deming, New Mexico, which received 4,700 migrants in 2019, more than a third of the town’s population, mostly between the months of April and July. Now, from 100 miles away in El Paso, Garcia was coordinating with Deming’s officials to arrange transportation for migrants there.

With a tired sigh, Garcia struggled to capture the dilemma these towns are facing. “So, I’m Border Patrol, you’re the mayor of Deming,” Garcia said. “I call you and say, ‘I’m gonna release 150 people.’ You say, ‘You can’t do that.’ And I say, ‘Here’s the phone number to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, be my guest.’”

Shifting responsibility for the releasing of migrants from ICE to Border Patrol, the enforcement arm of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, was a huge change to official Department of Homeland Security policy. It followed the quiet termination in October 2018 of the “Safe Release” system, which since 2009 had involved Border Patrol and ICE agents providing asylum-seekers with a phone to contact family or friends already living in the country, and delivering them to a bus station or airport with their tickets already booked—or to a humanitarian shelter that could assist with travel. The end of Safe Release set the stage for a highly localized humanitarian crisis when the number of asylum-seekers began to rise this spring—soon after, the Trump administration announced a national emergency on the border, citing the “sharp increases” of asylum seekers in border towns.

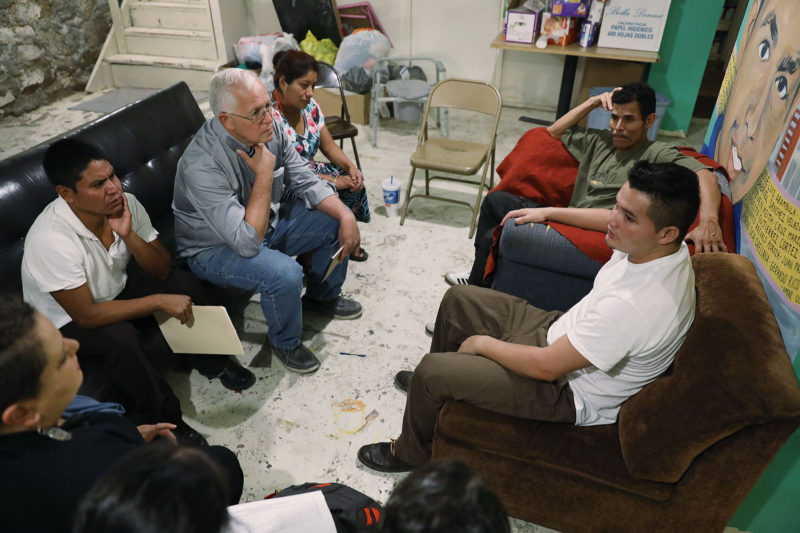

Ruben Garcia (2nd L), director of the Annunciation House, talks with asylum seekers as they wait at the Annunciation House to hear from the Office of Refugee Resettlement about their children after being released from U.S. Customs and Border Protection custody on June 25, 2018 in El Paso, Texas.

Image: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

According to a letter undersigned in May by the mayors of 22 cities in border states, some 168,000 migrants traveling in the previous six months received care from local governments and humanitarian centers, forming a regional network that served as de facto refugee resettlement agency. The brunt of the effort was borne by smaller cities near the border. Hundreds of huddled migrants left on street corners; missing paperwork; a daily scramble for available beds—all the tumultuous result of the Trump administration’s refusal to deal with the fallout from its own immigration policies.

This report was based on conversations with more than a dozen local officials and humanitarian aid workers, as well as a review of internal communications between officials in El Paso and the Rio Grande Valley—the two CBP sectors where refugee border crossings were highest in the spring. These interviews and internal records reveal an informal system of asylum assistance highly dependent on overworked volunteers, and document the immense strain placed on cities, towns, and nonprofits that have attempted to help the migrants. They show, at the very least, a woeful pattern of incompetence and neglect on the part of the federal government. They may also show something more nefarious: a concerted attempt to create a climate of crisis by detaining and releasing migrants in the most chaotic way possible.

On that morning in June, Garcia thumbed his iPhone, communicating with various officials: El Paso Mayor Dee Margo; El Paso Congresswoman Veronica Escobar; the city’s fire chief, a county judge, a commissioner, a county attorney, even a campaign staffer for Beto O’Rourke. On at least three occasions, the office of New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham provided him with buses to take people out of Texas. Garcia’s unofficial jurisdiction included not just Deming and El Paso, but also Dallas in Texas; Lordsburg, Mesilla, Chaparral, Anthony, and Albuquerque in New Mexico; and, occasionally, even Denver, Colorado. As the liaison handling arrangements among dozens of shelter spaces, cities, counties, and federal agencies, he was the only one who knew how much bed space was available on a given night.

As we were talking, a group of 60 adults and children entered the cafeteria of the Casa Oscar Romero and sat at the long table, unfolding the chairs resting against the walls. In the kitchen, volunteers dished piles of fried chicken into large metal bowls. The building also had rooms with beds, blankets, and toys; on the walls were instructions for how to read plane and bus itineraries. A map featuring all of Greyhound’s routes across the country was posted near the entrance, where a boy squirmed on a bench.

- ‘Normally it’d be a federal employee doing a lot of this work, and we have volunteers doing it.’

“Welcome! I bet you’re all tired of riding on buses,” Garcia bellowed in Spanish, as the families filtered into the cafeteria.

“Yes, very tired,” one woman offered.

“Well, good, the bus ride is over.”

As people lined up to receive plates of chicken and biscuits, Garcia showed me a receipt for the food totaling more than $500. In all, Annunciation House has paid roughly a million dollars this year on hotel room accommodations alone for asylum-seekers, Garcia said. A full accounting is difficult to make, since the effort is spread out among so many towns and cities, stretching all the way from Texas to California. In July, as part of a $4.5 billion package ostensibly to improve detention conditions at Border Patrol and ICE facilities along the border, Congress budgeted $30 million to reimburse governments and nonprofit organizations that had spent resources on the improvised resettlement effort. But to qualify for this support, they would have to apply to FEMA for the funds, which would be distributed on a first-come, first-served basis. The amount will almost surely fall short.

Furthermore, the heavily bureaucratic method to apply for the funds, which requires applicants to submit estimates through layers of bureaucracy within FEMA’s Emergency Food & Shelter Program, disadvantages the countless smaller churches, ministries, and community groups that burned through money and resources assisting tens of thousands of asylum-seekers, sometimes without keeping careful records. Reimbursement requests submitted by larger nonprofits, such as Catholic Charities and United Way, are more likely to be successful because they are represented on the national FEMA board that decides which applications to greenlight.

For their part, Garcia said Annunciation House would not apply for reimbursement, in order to avoid the taint of association with the federal government. But Garcia said he would welcome federal assistance, should the city receive it, with the major expense of transportation, which Trump’s national emergency declaration appears to authorize.

“If the military is to be used to assist Border Patrol with the influx of arriving refugees,” Garcia later said in a press release, “then the military’s transportation capabilities should be used to transport refugees to faith communities in larger cities who can receive and assist refugee families.”

A nearly 800-mile drive from El Paso, in the town of McAllen, Texas, Sister Norma Pimentel has been at the forefront of migrant family arrivals since 2014. Pimentel oversees the ever-relocating Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley respite center in this town, where asylum-seekers are transported after their release from detention at Border Patrol facilities. Before this year, the number of people arriving at her door ranged from less than a dozen a day, to so many that they had to take refuge in large emergency tents propped up behind a church in the city’s downtown district.

Nothing, however, prepared Pimentel for the overwhelming number of people released by Border Patrol this year. Previously, according to The Monitor, the high water mark for Catholic Charities in McAllen was October 2016, when the nonprofit cared for 5,600 people. That number nearly doubled to 10,645 in March of this year, including a single day that month in which the center accommodated more than 1,300 people—an unprecedented number for a 24-hour period, in a space designed to hold just a few hundred.

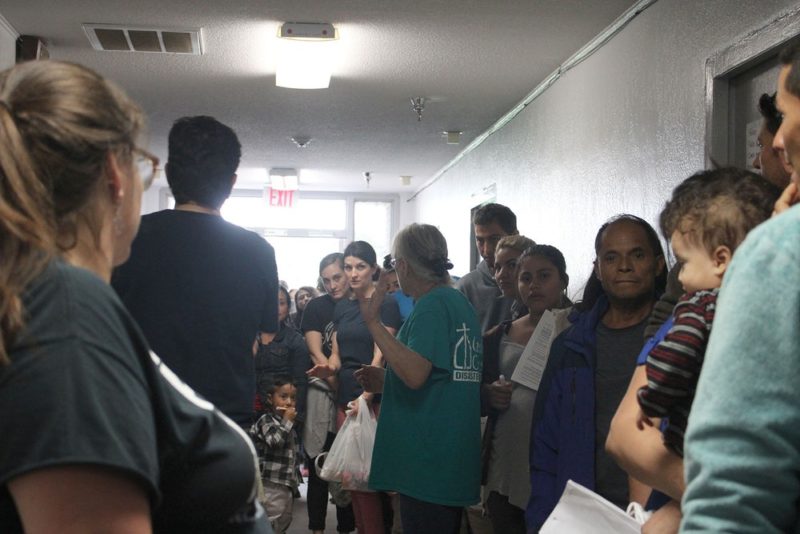

Sister Norma Pimentel greets immigrants recently released from detention at a Catholic Charities center on June 17, 2018 in McAllen, Texas. Image: LOREN ELLIOTT/AFP/Getty Images

During a visit in March to the building, I saw lines of people spilling out the front door, waiting to receive clothing for children and infants. Nurses were checking people who seemed sick, and a volunteer helped families make travel plans. There was a sense of ordered chaos; volunteers wearing teal vests raced around the facility, speaking with migrants, and ordering food.

The week before, Border Patrol had given Pimentel only three days’ notice that it was going to release thousands of people per day into McAllen, Brownsville, Harlingen, and other cities across the Rio Grande Valley for the foreseeable future—a pace that didn’t start to dissipate until the summer. Previously, Border Patrol agents would inform Pimentel well ahead of time that they were transporting families directly to Catholic Charities in McAllen, including how many and when. But now, as in El Paso and elsewhere in the Rio Grande Valley, border agents were dropping off migrants directly at bus stations instead of at local organizations like the Catholic Charities building. It was a change that confused Pimentel.

“My surprise mostly has been the fact that they started distributing them throughout the whole [Rio Grande Valley],” she said. “You know, why are you dropping them off at the bus stations, when you have always brought them to us? Why change that? For me, it was a big question mark. Like, why would they want to do that? It was almost as if they were causing chaos.”

In March, in the city of Brownsville at the very southernmost tip of Texas, city officials and volunteers were also left questioning the motives of Border Patrol agents after they dropped off about 50 asylum-seekers on a street corner in the city’s historic downtown district—half a mile from a Greyhound bus station. On that day, there were only a handful of volunteers at the Good Neighbor Settlement House, an old two-story building in a low-income neighborhood that provides a food pantry and bed space to migrants as well as the local homeless and poor.

Also, none of the people dropped off by Border Patrol had any of their official documents, which would have allowed them to travel within the United States—another unprecedented development. When Good Neighbor’s director was alerted of this situation, she led them inside the settlement house, where the group was kept separate from asylum-seekers who did have paperwork. Of the nearly 250 people accommodated that day, half were small children.

“Border Patrol dropped off two busloads of people, no documents, [meaning] we can’t even lend them a phone to make arrangements; they’ll just get detained again while traveling,” Belinda Bradford, a full time employee at Good Neighbor, told me. Two hours later, she recalled, “Border Patrol comes with a box, and says, ‘Oh, we forgot to give them their paperwork.’ Really?” She sighed. “Maybe they thought they could get away with it?”

- ‘I think it goes beyond negligence, I really do. Especially when you start talking about the treatment of human beings.’

It turned out that Border Patrol agents only brought the paperwork after they were contacted by Tony Martinez, then the mayor of Brownsville. Martinez told me that he suspected the agency was purposely creating an unmanageable situation to turn the Trump administration’s rhetoric about a crisis at the border into a reality. “There seems to have been an assumption that we couldn’t handle it, an expectation that we’re unable to manage” the mass release of asylum-seekers, Martinez said. “But I’m a problem solver, and if you give me a problem, I’ll give you your pick of solutions.”

Ronald Vitiello, former acting chief of the Border Patrol under President Obama and acting director for ICE until he was ousted by Trump in April, claims that post-release planning was simply not his job. Neither “CBP nor ICE are appropriated [by Congress] for this after care, we [did] it because it’s a best practice and because it makes sense and helps communities and our relationships with these towns, but nobody in the government is funded for that,” he said in a phone conversation. “These mayors and the cities, they came to expect a service brought to them by the government, they got used to it, [and] when the numbers overwhelmed everybody, they looked to us to fix it.”

A preview of the federal government’s new position toward released asylum-seekers came last October, when officials with the Department of Homeland Security informed humanitarian groups in San Diego that agents would no longer help with post-release planning. The policy was clarified on March 27, when then-CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan said that CBP and ICE would begin releasing asylum-seekers en masse into border towns. In front of the bollard border fence and near the Paso del Norte International Bridge in El Paso, where migrants were being held behind razor wire, McAleenan, now the acting secretary for the Department of Homeland Security, painted a grave picture of CBP facilities bursting with human beings, a situation he called unprecedented. The mass releases were being done with reluctance, he said.

“It represents an increase in flows that will follow,” McAleenan said. “That is not something we want to do, it is something we have to do given the overcrowding in our facilities.”

By that point, mass drop-offs of migrant families had already been occurring for a few weeks in El Paso, as well as sporadically in late 2018. On March 15, the city’s fire chief, Mario D’Agostino, emailed ICE official Marc Moore pleading with the agency not to release additional migrants into the city because shelters were at capacity. That request was ignored, and 147 people were dropped off at El Paso’s downtown bus station four days later—prompting the local office of emergency personnel to dispatch employees who then assisted migrants with purchasing tickets. The city regularly uses its own resources in such situations, deploying their own EMT staffs, for example, to screen migrants who have often been held in crammed and fetid conditions, with critically deficient access to hygiene products, sleeping space, and nutrition, leaving many in precarious health after an often harrowing journey.

A total of 35,000 of these asylum-seekers passed through a network of hospitality centers in El Paso, Las Cruces, and Albuquerque between December and March, according to D’Agostino. The direct releases were so overwhelming that Rep. Escobar, the congresswoman from El Paso, in a March 1 letter begged McAleenan “to alleviate some of the local burden that falls on my community.”

Though agents are supposed to detain migrants for no more than 72 hours, the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general observed that 3,400 of 8,000 detainees at several different Border Patrol stations in the Rio Grande Valley during early June had been held for longer, with many stays longer than 10 days. In April, a government inspector visited a station in Clint, Texas, near El Paso, and found hungry children and adults living in lice-infested cells for weeks on end, sometimes being taken to a quarantine cell if they contracted scabies, chickenpox, or other diseases.

Volunteers with Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley facilitate the arrival of asylum-seekers to a respite center in McAllen, Texas, on March 23, 2019.Image: Aaron Cantú

The fact that Border Patrol has exerted wide discretion over who it detains, and for how long, made some immigration attorneys wonder whether agency leaders were timing the release of migrants for maximum impact. Back in the Rio Grande Valley, for example, The Monitor reported that asylum-seekers were being held in Border Patrol custody for as long as ten days—even as the agency publicly claimed facilities were at “critical capacity” and unable to handle the increased numbers of new arrivals. The prolonged detentions didn’t make any sense, argued attorney Karla Vargas of the Texas Civil Rights Project, for an agency trying to clear bed space as quickly as possible. She sees this as a sign that the agency may have chosen to do mass public releases for cynical reasons.

“Why are these empty, if we have this chaos happening at the [CBP] processing centers?” Vargas said. “I think it’s part of the narrative that the administration is trying to put forth that CBP is being overrun by immigrants, and therefore they need more money, when in reality it’s the way they’re mismanaging people and focused on stockpiling people in these processing centers instead of getting them to the next phase of the immigration process.”

Garcia, the director of Annunciation House in El Paso, also suspected a “political dimension” to the timing of the chaotic mass releases. “I think it goes beyond negligence, I really do,” Garcia said, “Especially when you start talking about the treatment of human beings.”

The first locality to challenge the Trump administration’s decision to end its Safe Release policy was San Diego County, which voted in April to sue the current and former heads of ICE, CBP, and Border Patrol for what it called a “sudden and unlawful change in policy.” The complaint alleged that the policy shift meant that border agents were now releasing asylum seekers from federal detention without “the previously-provided assistance in reaching their final destination(s) outside the County.” The suit seeks a reinstatement of that assistance and reimbursement for the resources San Diego has devoted to caring for asylum-seekers.

That assistance, the San Diego lawsuit said, had long included helping asylum seekers locate contact information for relatives residing in the U.S. and facilitating phone calls between asylum seekers and those relatives. ICE would then transport people to points of departure, such as bus stations, train stations, and airports, and even offer food for the journey. It remains unclear, according to the complaint, why this policy was ended; it came to an abrupt halt, without explanation, last year.

The San Diego suit caught the attention of officials in New Mexico and West Texas. Albuquerque eventually filed a joint lawsuit with the state of New Mexico, citing duress similar to that claimed by San Diego County—and the newer suit goes into far more detail about the state resources deployed to pick up the federal government’s slack. It alleges that the New Mexico office of the attorney general, as well as the state’s youth and family services department and office of emergency management, spent resources investigating reports of human trafficking, while workers for the state labor and transportation departments were directed to coordinate travel plans for asylum seekers. In addition, according to the complaint, state police were on alert in communities receiving large numbers of people, and the state sent $750,000 in emergency grants to the cities of Deming and Las Cruces and Luna County to manage migrants rapidly being released from federal custody.

There were other public safety consequences, well beyond the scope of the lawsuits. With the number of families crossing the border on the rise in April, a far-right militia group made national headlines after its gun-toting members filmed themselves briefly detaining hundreds of migrants along the border, a few dozen miles south of Las Cruces. On April 15, just three days after Border Patrol began dropping off asylum-seekers there, one extremist called the city threatening to take action “if necessary.” A few months later, somebody called in a death threat to the mayor’s office, requiring the police department to assign several cops to trail the mayor at a city council meeting.

In an interview, Mayor Ken Miyagishima blamed the president’s rhetoric for the elevated threats. “They hear the top elected official in the U.S. making [anti-immigrant] comments, and it just lends itself to the animosity among friends, neighbors, relatives,” Miyagishima said.

Las Cruces accommodated 16,750 refugees since April, according to its own count, and still received about 150 daily until recently. After rushing to supply transportation between local hospitality centers, bus stations, and airports, the city agreed to put up $500,000 toward city worker overtime pay, partial reimbursement for local non-profits providing refugee hospitality services, and rent for an old armory near downtown that now acts as an unofficial central processing center. The money came from a special fund the city generates by leasing out a hospital building.

“Very few cities have this fund like I’m describing to you,” Miyagishima said. “And if you stop and think about it, what about all the savings that the federal government is saving right now? Normally it’d be a federal employee doing a lot of this work, and we have volunteers doing it.”

According to the city’s interim manager, William Studer, the city was planning to submit a list of expenses to FEMA’s Emergency Food and Shelter National Board Program in late July, and was hopeful that funds would be disbursed within 60 days of approval. FEMA is supposed to reimburse funds already spent as well as supplement future expenditures through September 2020, covering such items as food, lodging in shelters or hotels, transportation costs, and basic necessities like hygiene products and diapers. Las Cruces expects to spend $90,000 per week for the next year. Together with the half million in reimbursement it’s already seeking, that will put its total request at $5.5 million.

And that’s just one town.

With only $30 million budgeted by Congress, it’s difficult to see how every town or nonprofit organization that contributed to the relief effort will be fully compensated by the federal government. The costs to Annunciation House and the city of McAllen each reached at least $1 million, while the state of New Mexico and the city of Albuquerque claimed total expenses of $1 million. Among Las Cruces, McAllen, and the state of New Mexico, that’s already approaching a third of the budgeted funds. Yet nearly two dozen other cities likely expended far more than usual on caring for asylum-seekers, including Los Angeles, San Diego, Berkeley, Dallas, Denver, Austin, Phoenix, and Tucson, and a smattering of smaller towns in all four border states.

Although charities can request funds, it’s hard to imagine the smaller ones successfully navigating a bureaucratic process that hasn’t been widely publicized.

On a Tuesday evening in early June, I checked in with one of these charities: Mustard Seed & Rainbow Ministries, a tiny church located in Chaparral, New Mexico, a community some 30 miles southeast of Las Cruces. The setting sun cast orange and purple hues over the red earth. Inside, rows of mustard-colored pews filled the main hall, while smaller rooms were stuffed with cots, piles of dirty laundry, and boxes of clean donated clothing and hygiene supplies.

Since February, the church had been taking in about 60 asylum-seekers at a time from nearby El Paso. By the time of my visit, their last group had numbered around 25. While Pastors Joe and Iliana San Nicholas said they found their work spiritually rewarding—the church’s Facebook page features videos of asylum-seekers singing Christian songs—they were both clearly exhausted. During the weeks when migrants stayed with them, they sometimes had to stay awake until four in the morning waiting with them at the bus station—only to then have to transport another group to the airport a few hours later.

“It’s been rough,” Iliana said. “But I understand, as a Christian and as a pastor, that when you start tapping into the kingdom of God and what God expects us to do, [helping refugees] is one of them, because God loves the immigrants.”

A Guatemalan woman looks at a map of the United States at The House of Refugee, a new center opened by the Annunciation House to help the large flow of migrants being released by the United States Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement in El Paso, Texas on April 24, 2019.Image: PAUL RATJE/AFP/Getty Images

For weeks, Iliana had tried asking the city of Las Cruces for financial help. Officials gave her the run-around, she said, and in the end told her that the funds it was sending to nonprofit organizations were only for those based in the city proper. The couple estimates they’ve spent more than $10,000 of their own money on the effort, handing out cash to families and purchasing backpacks, clothes, food, soap, toothpaste, and gasoline. They’ve barely scraped by. The church’s small septic system wasn’t able to handle the volume of people using the facilities, and had to be replaced at a cost of $3,700—a discount, Iliana said, offered by a plumber connected with the church. When asked in early August if she planned to apply for FEMA funds, Iliana said it was the first time she’d heard it was possible.

At the bus station in March in downtown McAllen, the city’s old, clustered core, about two dozen asylum-seekers waited to buy bus tickets, clutching manila envelopes containing documents from CBP and ICE. Their intended destinations were written on the front of the envelopes. It has been a familiar sight since 2014, but a near constant one this past March.

One of these asylum-seekers was Suyapa, from a small fishing village near the capital of Honduras. She and her family had made their living by fishing, but said that gangs demanding bribes to operate their boat made the business impossible. So she fled with her daughter, who sat nearby blowing on a noisemaker as the pair waited to board a bus to Dallas.

In Honduras, Suyapa said, her eyes misting with tears, “I couldn’t work anymore, I couldn’t bring home bread for my children.” After walking to the border for three months, she was held at a Border Patrol processing facility in McAllen known among migrants as the perrera—the dog kennel—for its cage-like cells. Then Border Patrol took her and her daughter to the city’s Catholic Charities respite center, where she received fresh clothing and volunteers ordered pizza for her cohort. She planned to stay with a friend until her asylum hearing; in the meantime, she will have to periodically check in with an ICE officer by phone.

Americans, she said, “need to understand that if we come here, it’s out of necessity, because we’d rather live back home. Life there, the gangs make it so difficult.”

Suyapa was arguably one of the lucky ones, arriving in the U.S. before the federal government expanded its Remain in Mexico program, which requires most Central American asylum-seekers to wait in Mexico for their day in an American court. Since its implementation, the number of asylum-seekers arriving to humanitarian centers in McAllen, Brownsville, and El Paso have significantly fallen, from hundreds to as little as a dozen or fewer a day. Piloted in San Diego and then El Paso, the program was expanded by the Trump administration in an arrangement with Mexico across the entire border beginning in June, with Mexico expecting to receive as many as 60,000 asylum-seekers to Mexican border cities, where the threat of violence and kidnapping is so severe and access to lawyers so difficult many have given up on their asylum claims. Recently, Mexican authorities in some cities have transported asylum-seekers deeper into the country, as far as Monterrey, in northeast Nuevo León, and even Chiapas, on the border with Guatemala. The policy and others are apparently meant to block asylum-seekers, as one National Security Council official admitted in an internal email. The Supreme Court on Wednesday upheld the policy.

On the diplomatic front, the Trump administration in late July strong-armed the Guatemalan government—the top sending country for families this year—into accepting a “safe third country agreement” in which migrants who passed through Guatemala would be required to first seek asylum there. The national asylum agency in Guatemala employs less than 10 people; the move appears to be yet another impossible barrier meant to discourage people from requesting asylum in the U.S.

For Ruben Garcia in El Paso, the federal government’s callous position on asylum is a moral crisis of historic proportions. At the Annunciation House in early June, while he was still regularly assisting upwards of 500 asylum seekers a day, he compared the responsibility of caring for and housing refugees with past tests of the nation’s character, including the Civil War. This is one of those moments, he said, when the country defines itself. “When we say, ‘All men are created equal’ in 2019, it has to include migrants and refugees,” he said.

“It’s very inconvenient to have tens of thousands of refugees arriving. It’s very inconvenient. It’s a lot of work. But it’s eminently possible,” he said. “That hard work is what makes us who we are. That’s where our pride comes from. Let’s be busy with that.”

This article was reported in partnership with Type Investigations.