But with this disease, “those put on ventilators stay on for weeks, several days at a minimum,” said Ruthanne Sudderth, the top communications official with the Michigan Health & Hospital Association. “So even with the shortages, you see a surge because of the time people are on them, and that compounds the shortages.”

As hospitals began to run low on ventilators, Henry Ford leadership circulated a draft memo outlining guidelines for making life-and-death decisions that prioritized saving healthier patients. Officials there said it was an internal document outlining policies for a “worst-case scenario” that never materialized. At Sinai-Grace, doctors debated whether to offer the hospital’s 70 ventilators to those over 65 years old, said critical-care physician Lobelia Samavati. She and others strongly opposed any such policy.

“I came to medicine to take care of patients, and I don’t want to play God,” Samavati said. Sinai-Grace ultimately received 10 more ventilators and never put the policy in place, she said.

There are moral risks, but also physical ones. While health care workers would typically dispose of masks after treating each patient, there aren’t enough masks to do so right now at many hospitals. Forced to adapt, DMC infectious disease specialist Teena Chopra developed rules for folding reused masks and placing them in bags to prevent cross-contamination. DMC residents turned to GoFundMe to raise more than $32,000 to supply their emergency department with better masks and other PPE.

But many workers worry that limited supplies and high-exposure situations could lead to more doctors and nurses getting sick. COVID-19 symptoms had sidelined over 1,500 staffers in Beaumont’s system and 700 staffers at Henry Ford’s hospitals by April 5. At least four had died.

In the intensive care unit at Sinai-Grace, a team of seven doctors and residents who typically treat 18 to 30 patients at a time were now responsible for 40 to 50 patients.

DMC, which typically schedules seven to 10 emergency room techs per shift, was working with as few as two on some shifts, said Moore. To protest low staffing levels, nurses staged a brief work stoppage on April 6.

But Moore wasn’t able to join any demonstrations of discontent. She’d already gotten sick herself. She came down with a fever and cough in mid-March. When her symptoms didn’t subside, a doctor ordered her to quarantine for another two weeks. She remains off-duty until at least mid-April.

“My phone rings 24/7 and I’m still actively working from home advocating for members, fielding calls all day long, because no one else is listening or picking up the phone right now,” she said of her duties as a union steward. Moore instructs workers on what to do if they aren’t feeling well or if they feel like management is overstepping boundaries.

Each health care worker who is not adequately protected is at risk of getting sick. And every worker who gets sick is one less fighting the disease.

Chris Wasen, an RN on a COVID-19 step down floor, stands for a portrait near a window of his home in Macomb, MI.Image: Seth Herald for HuffPost

Even when they do show symptoms, providers still have a hard time getting tested. There just aren’t enough supplies. Workers are triaged according to priority levels set by the state. For those who can’t get a test, hospitals must assume the worst and quarantine anyway. One Henry Ford nurse practitioner was exposed to co-workers who tested positive, but couldn’t get tested because the ER didn’t have enough swabs. She was sent home for four days as a precaution.

DMC’s Samavati called the early-April onslaught “the most difficult and stressful” situation she’s faced in 20 years in the ICU.

“The emotional part is affecting health care workers, physicians, residents and fellows because of the anxiety and fear that you are going to acquire it, the anxiety that you are not able to do anything about it, the anxiety that you don’t have the right protective equipment,” she said. “A lot of people — they can’t cope with it.”

Yet the conditions are creating a sense of camaraderie among health care providers, said Chopra, the infectious disease specialist. “We are all humans and we feel different kinds of emotions including sadness and ‘Why me?’ But then I also think that this pandemic has brought everyone closer.”

At Henry Ford, the clinical psychology unit now treats its hospital colleagues with a hotline and three virtual group therapy sessions a day.

When a COVID-19 patient is discharged, Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” plays on the loudspeaker. At Beaumont, it’s The Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun” when someone comes off a ventilator.

“Yesterday, they played it five or six times,” Wasen said. “That was nice.”

‘Is This Over Yet?’

Wasen has trouble sleeping before his shifts at Beaumont’s converted COVID-19 unit. But he shows up and changes into scrubs and gets his mask for the day — one to last the full shift, one that has already been used and disinfected. After a morning huddle, he keeps watch on about three patients for the next 12 hours.

Image: MSJONESNYC for HuffPost

He checks often on patients with high fevers, and monitors everyone’s vital signs at least three times a day. Because it’s an ortho floor, there aren’t pulse oxygen monitors in each room, so they use incentive spirometers — hand-held devices with a breathing tube and air chamber — to clear lungs. At mealtimes, Wasen checks the sugar levels of diabetics and gives them insulin. He also talks by phone with family members who can’t visit and need an update. His colleagues have had tougher tasks, like setting up video chats for dying patients.

His unit has also been receiving more nursing home patients with complicating conditions.

“Some of them, the look in their eyes, if they are not verbal, you don’t know what’s going on in their head,” Wasen said. He can only hold their hand.

This kind of work has led to fatigue and incredible stress for health care workers.

“Every morning I wake up and I’m like, ‘Is this over yet?’ because we’re always thinking about how people are suffering,” said Asha Shajahan, a family practitioner at a Beaumont clinic in an inner-ring suburb.

Samavati said she and other physicians work nearly nonstop, sleeping only four hours a night between their shifts in the hospital and their research into treatment and cures for COVID-19.

“The physician goes into this profession to treat patients and cure disease, but we don’t have the cure right now,” Samavati said. “We feel like we can’t do anything about it, and that’s where there’s sometimes a sense that we’re losing.”

Chila Harper who has fully recovered from COVID-19 stands outside her home in Redford, Michigan.Image: Seth Herald for HuffPost

They are also working against the cascading set of conditions that made Detroit uniquely vulnerable in the first place.

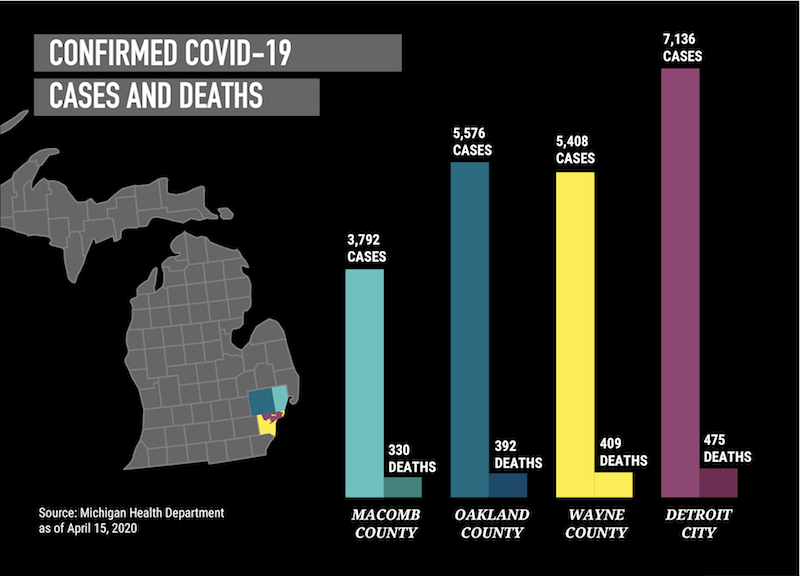

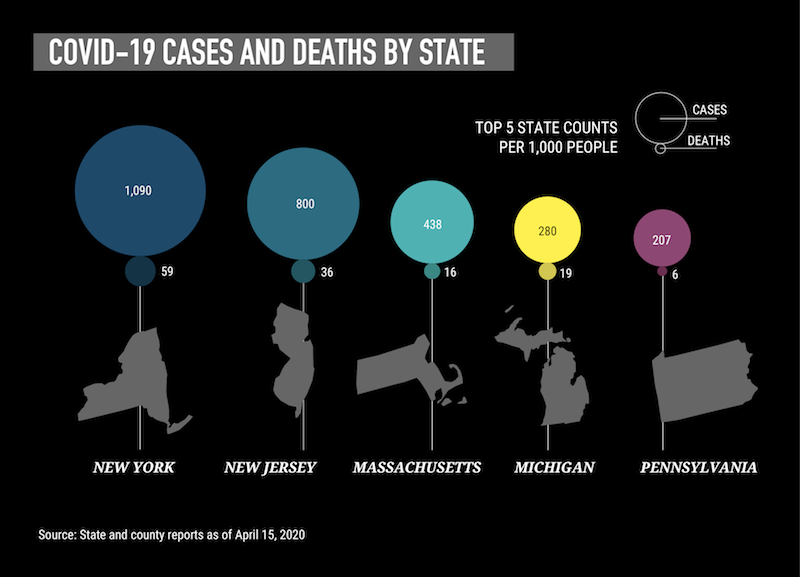

This is one of the most segregated regions in the country, where a separate-and-unequal system magnifies racial disparities. Research has found that city residents — 79% of whom are Black — live 16 years less than their suburban counterparts. The coronavirus amplifies a precarious pattern. Among those infected in the first weeks were prominent African American leaders: police chiefs and captains, a news anchor, a state representative. Even outside Detroit proper, Michigan’s Black communities are far harder hit than others. Nationally, available data shows that 42% of those who have died from COVID-19 were African American.

At the same time, more than one-third of Detroiters — about 224,000 people — live in poverty. This contributes to chronic health problems, like diabetes and hypertension, which in turn make people more susceptible to severe, potentially lethal complications from COVID-19. At a time when hand-washing is more important than ever, thousands of residents have endured water shut-offs.

A lack of access to health care exacerbates those conditions. With the help of the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid, the number of people without insurance in Michigan has declined significantly, leading to more care, better health outcomes and more financial security for the state’s poorest residents. But even with that improvement, more than 30% of the city’s residents had trouble paying medical bills in the last 12 months, according to unpublished survey data that the Center for Health and Research Transformation, a think tank affiliated with the University of Michigan, analyzed for HuffPost and Type.

Vern Davis Anthony, a former Michigan, Detroit and Wayne County public health director, said these disparities “put us behind some of the underdeveloped countries.” The virus, she said, “could really rupture our health care delivery system. I think we’re going to learn there’s no us and them. We’re going to learn the hard way we’re all in this together.”

Compounding the problem is a relative lack of private providers, in part because it’s harder to make money when so many patients are on Medicaid, which pays less than commercial insurance. “A lot of folks, they don’t have a provider, somebody to talk to when they get sick,” said Abdul El-Sayed, an epidemiologist and Detroit’s former public health director. “That’s a real problem in a situation like this.”

A patient waits to enter the COVID-19 testing site at the Michigan State Fairgrounds.Image: Seth Herald for HuffPost

Air pollution, which research recently linked to a higher death rate from COVID-19, is another chronic challenge. The Motor City is in a sprawling, car-dominated metropolitan region, which contributes to respiratory diseases that can be debilitating and even lethal. It has also struggled with toxins from a now-closed incinerator and a refinery. In 2019, Detroit had the 10th most asthma-related deaths of any American city.

The possibility of very sick patients overwhelming Detroit’s health care infrastructure is one reason that Gretchen Whitmer, Michigan’s governor, has been heeding the advice of her scientific advisers. In March, after a series of steps gradually restricting public activity, she effectively shut down the state except for essential businesses. In just the last week, some Republican officials and their supporters have said the stay-at-home order is too restrictive; Whitmer says it is necessary to relieve the pressure on hospitals.

Whitmer, like most governors, had expected the federal government to play a key role in pandemic management by, among other things, tapping its emergency stockpile and using wartime production powers to guarantee an adequate supply of essential medical gear.

But even as President Donald Trump activated the federal response, he told governors both publicly and privately that they would have primary responsibility for obtaining supplies like ventilators and N95 masks. Whitmer was among the governors who questioned that decision, in part because of the panic her office was picking up from hospitals.

“In southeast Michigan, one hospital had what they thought was a year’s supply of PPE,” a senior Whitmer administration official said. “They burned through that in a week.”

‘I Felt Like I Was Being Strangled’

Chris Wasen met Chilah Harper on a Saturday shift at Beaumont’s converted COVID-19 unit. A 43-year-old mother and nurse who works at Detroit’s Veterans Affairs hospital, Harper was now in need of caregiving herself.

Harper had awoken on March 16 with what seemed like the flu. Terrible body aches. A fever of 103.

“My fingers were hurting,” she said. “My feet were hurting. My whole body was aching to the point it was paralyzing. I couldn’t get out of bed.”

She forced herself up the next day. Beaumont had just started drive-up testing for both the coronavirus and influenza. Harper got tested and was told to quarantine at home. Her negative flu results came a day later, but for COVID-19 results, she had to come in for a second test.

Before those results came in, she woke up with a crushing headache and shortness of breath. “I felt like I was being strangled.”

She woke her daughters, 11 and 20, to say goodbye and drove herself to Beaumont’s emergency room.

“They weren’t doing any valet, so I had to park my car and had to walk from my car to the hospital, which was such a struggle,” Harper said. “They met me with a wheelchair. They took me to the ER, which was virtually empty. I went to the back very quickly and that’s when they started the critical care.”

The TCF Center in Detroit, Michigan has been turned into a 1,000 bed field hospital which will act as an overflow area for patients that have contracted COVID-19. The upper floor holds 600 beds for critically ill patients; the lower floor holds 400 beds for patients in recovery.Image: Seth Herald for HuffPost

Stable, but struggling, she was sent to Wasen’s unit.

At one point, a respiratory team had to be called in the early-morning hours as she fought for air. Another episode happened in the late afternoon.

“It was just so hard for her to get a breath,” Wasen said.

Oxygen helped, but she struggled when doctors tried to wean her off of it.

“I was scared to go to sleep. I was scared to lay flat,” she said. She kept her bed at a 90-degree angle. “I kept thinking I was going to die in my sleep.”

By the time Wasen met her, “she was just zoned out. You didn’t know if she was hearing you talk or not,” he said. And yet, that same day, she got herself up to take a shower, which Wasen noted with hope.

By Sunday, Harper reported a terrific night’s sleep. Her oxygen levels improved. It was a chore to move, but she moved. On Tuesday, nine days after she’d been admitted, Harper went home in the cool spring afternoon.

Keeping The Numbers At Bay

One of the ways that Beaumont and others are managing the pandemic is by keeping as many people out of the hospital as they can.

That means leaning more on outpatient doctors in hopes of lessening the pressure — and the exposure — in emergency rooms.

Beaumont health system has been treating about two-thirds of its COVID-19 cases remotely, mostly via “video visits,” said Shajahan, the family practitioner.

Their success is a bright spot, she said. She looks for signs that the person on the other side of the screen should seek emergency care. But if they’re suffering mild symptoms, Shajahan instructs them to take Tylenol and drink fluids.

Image: MSJONESNYC for HuffPost

“A lot of people who are going for COVID testing are being sent home because they wouldn’t benefit from being in the hospital at this point,” Shajahan said. “They can manage their symptoms at home.”

Detroit’s Cabrini Clinic, a free clinic in the Corktown neighborhood skirting downtown, does an analog version of this. Some patients call the clinic from outside and a staffer simply delivers their medicine to them. “The main anxiety for them is, will we still supply them with their medicines?” said Alisa Smith, a nurse practitioner.

Outpatient doctors like Shajahan have been handling about 22 online appointments a day, nearly all confirmed or suspected COVID-19 cases. But even telehealth takes a toll. Blocks of video visits with COVID-19 patients require more energy than the usual flow of in-person appointments, which are often easy checkups, medication refills and routine vaccinations.

An outbreak is something different.

“It’s all a lot more emotional,” Shajahan said. “Every single case is someone who’s afraid of a life-threatening virus, so it takes a lot more patience and time.”

Both policymakers and providers have spent the last month looking for ways to rapidly expand capacity. Even in the midst of a now-infamous back-and-forth between Whitmer and Trump, the governor has worked with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the state’s congressional delegation and local business leaders to find equipment wherever they can.

It helps that Michigan’s auto industry has deep connections to suppliers, especially in China, which is the world’s leading source of N95 masks. But the task is still daunting, in part because of the worldwide demand for supplies and the unruly market that developed as a result.

“If you’re not in the millions from an order standpoint, you’re also getting bumped on the ground in China,” a senior Whitmer official said.

Resourcefulness and charity are filling some gaps.

The state hospital association reached out to every private sector partner it could think of to get donated or purchased shipments, said Sudderth of the hospital association. In just one example, the utility company DTE Energy provided 100,000 KN95 masks. Ordinarily used for sewer work, they are roughly equivalent to N95s.

Detroit set up a drive-thru site on the state fairgrounds that could eventually test 1,000 people a day — albeit with a prescription — and it provided a $2 ride with home pickup for residents without transportation. Henry Ford figured out how to do its own COVID-19 testing early on, with results back in a day. After struggling with long waits for results, DMC is beginning rapid turnaround testing, with results in 24 hours.

Henry Ford also converted anesthesia machines to ventilators, said Steven Kalkanis, the group’s chief executive officer. Donations from Tesla and the Ford Motor Co. also added to its vent supply, giving it a secure foundation.

With cheery colors and fanciful drawings, a whiteboard in the Beaumont lobby tracks discharges. Some go straight home, but still need to take precautions. Others are ready to leave the COVID-19 unit but linger because there is no place to send them, even though Beaumont and Henry Ford converted some of their facilities for recovering patients.

Beds are still a precious resource. By March 30, DMC was transferring patients to hospitals in Pontiac and Ann Arbor as it ran low on beds, said Chopra, the infectious disease specialist.

Medical supply carts are organized and ready for uses in the assembly area at the TCF Center in Detroit, Michigan.Image: Seth Herald for HuffPost

In perhaps the most significant example of multiplying the state’s capacity to heal its sick people, the TCF Center, the city’s riverfront convention center, opened on April 10 as a 1,000-bed field hospital that military medics and volunteers will staff. It was constructed in nine days in the same mammoth building that hosted the Bernie Sanders rally last month.

It is now lined with 350,000 square feet of curtained partitions marking off makeshift rooms that each have their own supply of supplementary oxygen, as well as staff changing areas, a command center and a pharmacy. Air filtration systems have been engineered to provide negative pressure and cleaner air. Seventeen patients were being treated there as of Wednesday.

All together, up to 3,900 new beds across the state were brought online in a matter of weeks, said Sudderth. “Hopefully this will be a pressure release valve that helps the situation in southeast Michigan.”

A Looming Financial Crisis

All this massively expanding capacity comes at a cost. Skyrocketing prices for large amounts of equipment and increased staffing, including overtime, have exploded hospital budgets.

That’s especially the case with the suspension of revenue-generating procedures — which many institutions did voluntarily, before the governor’s orders. Smaller hospitals are at risk of shutting down for good. Within the Henry Ford system, 8,000 procedures have been canceled since mid-March, said Kalkanis.

Beaumont this week reported a net loss of $278.4 million for the first quarter of 2020. Henry Ford and DMC have not yet reported their lost revenue from canceled procedures, but the financial hits are likely to be staggering: tens of thousands of dollars lost for every knee replacement, mastectomy, angioplasty and heart bypass surgery, plus thousands of lost walk-in and well visits and tests like mammograms.

“This whole pandemic has put great financial weight on the shoulders of all kinds of hospitals of all sizes, in all parts of the state,” Sudderth said.

Michigan set aside $50 million for COVID-19 health care needs, although the big money will have to come from Washington, because only the federal government has the resources and isn’t encumbered by balanced budget requirements. The CARES Act, which Congress passed and Trump signed in late March, allocated $100 billion for hospitals, and $30 billion of that is already on the way to individual institutions in the form of direct subsidies based on how much they billed Medicare last year. But it might take still more government money to keep hospitals, especially rural and safety net institutions, from going under.

“None of it can come fast enough,” Sudderth said. She hopes the funding will come with enough of a reserve to help hospitals through future emergencies.

Trinity Health announced that it will furlough 2,500 employees, or 10% of its staff, at eight hospitals across Michigan, including the Detroit suburbs. It is meant to make up for a 50%-60% loss in revenue since the crisis began, according to the announcement. Executive pay will also shrink. Over at DMC, an emergency nurse who works with COVID-19 patients learned by email that staffers are having their 401(k) contributions postponed. Some underpaid nurses have left for better contracts in New York.

A Michigan National Guardsmen assembles walkers at the TCF Center.Image: Seth Herald for HuffPost

Yet, for all this, there has been good news. Henry Ford had a milestone: As of last Friday, more people were weaned off ventilators than put on them. Word came a few days later that a second field hospital scheduled to open in a Detroit suburb had scaled back from 1,100 beds to about 250, and the University of Michigan health system put on hold its plans to convert an indoor track facility in Ann Arbor into a hospital, citing a COVID-19 curve that appears to be flattening.

At Sinai-Grace, doctors now have a handle on the influx of nursing home patients, Chopra said. She and a team led by the city of Detroit undertook a massive effort to test every patient in the city’s 26 nursing homes, and those with positive results are being isolated and treated.

Deledda, from Henry Ford’s emergency room, gives a lot of credit to the stay-at-home order, which he is convinced has slowed the spread around Detroit significantly. But, he said, it also helps that he and his colleagues have learned to treat patients more effectively — for example, by positioning them on their bellies, rather than their backs, in order to better oxygenate their lungs.

A physician colleague from Henry Ford’s West Bloomfield Hospital, Steven Rockoff, said the early use of steroids to reduce lung inflammation also seemed to help, even though early guidance out of China suggested the opposite. “We are learning as we go. … There’s no playbook on this yet,” Rockoff said, noting that Henry Ford has changed its treatment algorithms “probably four or five times already.”

The doctors are sharing these insights and comparing notes with counterparts all over the world. And at two hospitals, they are part of more formal efforts to improve COVID-19 treatment. Beaumont announced this week that it’s staging the nation’s largest study on COVID-19 antibodies to find out if people who get the virus can get it again, and how long it takes before it’s safe for people to return to public life.

Perhaps nothing would be more significant than finding an effective way to treat or prevent contraction of the coronavirus. And although most experts say it will be months and probably more than a year before a vaccine is widely available, Henry Ford is heading the first large-scale study in the U.S. on the use of an anti-malarial drug in preventing COVID-19.

Doctors already prescribe hydroxychloroquine as an off-label treatment for the sickest patients; this study will investigate its true effectiveness. In another Henry Ford study, researchers are looking at the antiviral remdesivir as treatment for adults with severe cases of COVID-19.

In announcing these studies, Henry Ford’s chief executive sounded a Churchillian note.

“Unfortunately, we’re now a hot spot in the United States,’’ Kalkanis said. “But Detroit has always been the comeback city. Detroit turned car factories into tank factories and won World War II. Detroit stands for resilience. Detroit will lead the country in our war against COVID-19.”

The work will continue, even on the other side of the crisis.

“We’re going to learn a lot about pandemic planning from this experience,” said Sudderth. “I don’t think the system as a whole was well prepared for an international, worldwide pandemic.”

Awaiting The Other Side Of The Curve

When Chris Wasen returns home from work, he comes in through the garage. He strips to his underwear, puts his clothes in a plastic bag, and uses a disinfectant wipe to open the door. His clothes go right in the laundry.

Then he takes a hot shower and tries to block out the day. “Most people feel they could shower forever and they’re never getting clean,” he said.

But anxiety is a live wire. Once he is away from the endless demands of the COVID-19 floor, the feelings flood him.

One day in early April, Wasen discharged five people. This was big news. He hadn’t discharged anyone the week before. It was a pretty good day, maybe even the beginning of a downslope on that deadly curve.

At the end of his shift, a nurse approached him. It was her first day in the unit, and a patient had called for help. His wife was in the ICU. They were about to take her off the ventilator.

“We set it up so we could wheel the patient up there to see his wife for 15 minutes to say goodbye before we brought him back,” Wasen said, his throat catching. “That’s how the day ended.”

He tried to remember that five people went home that day, feeling more themselves than they had in weeks. It was a good day.

But still, he said, “you just can’t imagine.”