On a cold morning this past February, a 9-year-old resident of Iraq’s Khatuniya village took his family’s livestock to graze in nearby meadows. When he didn’t return by late afternoon, two relatives went looking for him. The next morning, the two men, Qasem Mohammed and Abd Mohammed Sabah, were found dead on a dirt road outside the village.

The killings bore the hallmarks of Islamic State attacks the villagers knew all too well—the men were found with their hands tied behind their backs and bullet wounds in their heads. Still, they came as a surprise. For nearly a year, the area had enjoyed a relative respite from violence, the result of a systematic campaign of raids conducted jointly by Iraqi and U.S. troops in late 2018 and early 2019.

The raids, reported here for the first time, picked off one Islamic State member after another, gradually uprooting the militants from villages and forcing them to retreat to nearby mountain areas.

But the attack in Khatuniya in February marked the beginning of the Islamic State’s return to the area—a resurgence that seems to be tied to the ongoing escalation between the United States and neighboring Iran.

That friction peaked when the U.S. assassinated the Iranian military leader Qassem Suleimani on Iraqi soil in early January of this year. In response, the Iraqi prime minister and parliament both called for the withdrawal of foreign troops from Iraq. The U.S.-led coalition suspended its activities to boost protection of its own forces.

“When the tensions between the U.S. and Iran increased, the frequency of the raids went down in this area, and ISIS activities went up,” said Hassan al-Soofy, a local intelligence officer who discovered the bodies of the shepherds in Khatuniya. “The situation became suitable for them [Islamic State fighters] and it helped them move.”

Since February’s Khatuniya killings and the disappearance of the boy, who was released after being held briefly, the Islamic State has claimed responsibility for hundreds of operations—from attacks on civilians to coordinated ambushes against security forces. The group has also capitalized on the coronavirus pandemic, which forced the coalition to evacuate most trainers. Iraqi security forces redeployed some of their troops to urban areas to enforce lockdown measures.

“We are terrified at night,” said Hamid Muhsen, the mukhtar, or village chief, of Khatuniya, located in Riyadh district in the northern Kirkuk province. “I swear, the situation isn’t good. ISIS is present in the village.”

Experts believe that the Islamic State has not yet restored itself to the military capability that enabled the group to capture significant swaths of territory in 2014. But the U.S. coalition that helped defeat it and keep a lid on its insurgency is scaling down. Although hostilities have slightly cooled off, the skirmishes between the United States and Iran earlier this year will likely pave the way for a permanent reduction of American troops in Iraq—further improving the Islamic State’s prospects.

Friction between the U.S.-led coalition and Iranian-backed armed groups, called the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), have long complicated anti-Islamic State operations in Iraq. But the U.S. assassination Suleimani and the PMF’s deputy commander, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, in Baghdad earlier this year raised fear of a U.S.-Iran war on Iraqi soil.

By the time tensions cooled down and the coalition began ramping up support again, a second round of escalation in March resulted in the deaths of three coalition personnel, accelerating troop withdrawals from several bases in Iraq that had been used to stage joint operations against the Islamic State. The U.S. and Iraq are set to renegotiate the terms of their military cooperation in June.

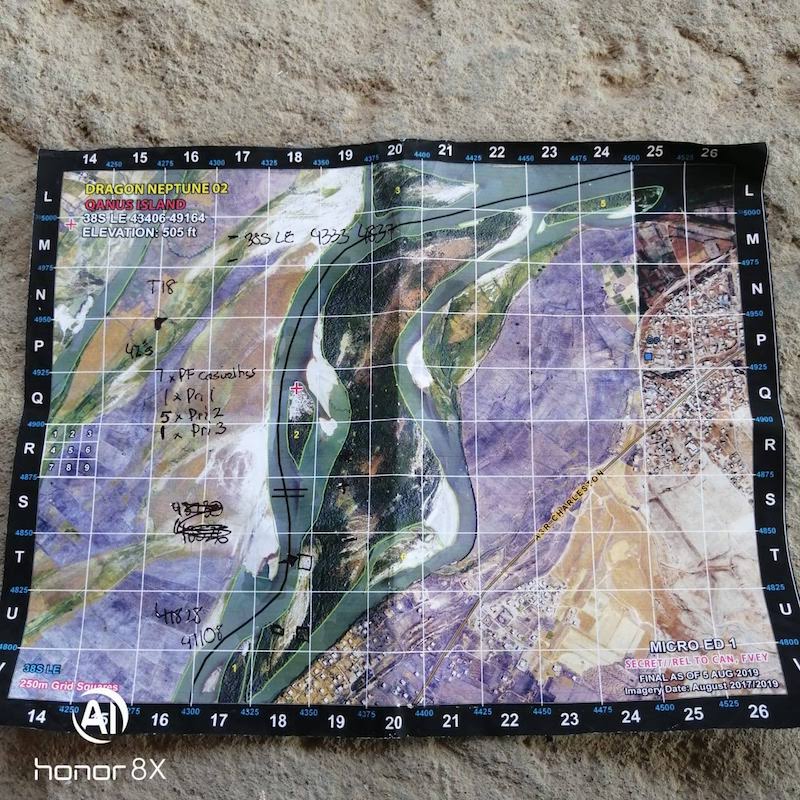

A map left behind by coalition forces at a military base in Kanoos. The handwriting appears to indicate a total of seven casualties incurred during the mission.Image: Simona Foltyn

Iraqi commanders insist that “on the battlefield, it’s only Iraqi troops,” in the words of Gen. Talib al-Kinani, until recently the top commander of the Iraqi Counter Terrorism Service. Maj. Gen. Eric Hill, the commander of special operations for the U.S.-led coalition, echoes this message, maintaining that the main role of the special forces was to train and advise Iraqi partners. “I would say largely these are Iraqi-driven and Iraqi-executed missions. There’s on occasion times where we will go out into the field with them in an advisory capacity, but the Iraqis are executing the mission,” he told Foreign Policy.

But conversations with dozens of civilians and security forces on the ground suggest that the direct involvement of U.S. ground troops in operations was a regular occurrence in 2019, with several such raids conducted per month. American ground troops coordinated airstrikes, processed intelligence, and—contrary to the coalition’s official position—engaged in combat. Two Iraqi officers whose forces partner with U.S. special operations forces told Foreign Policy that during these joint missions, Iraqi and American soldiers moved together as “brothers in arms.” (No media have been allowed to join these special operations.)

Foreign Policy investigated several such missions—conducting interviews in rural areas of the Kirkuk and Nineveh provinces. The raids were mostly carried out under cover of darkness, and at least two of them resulted in American casualties. While many villagers suspected that Americans participated in the operations, their involvement became evident only when missions went awry, forcing the troops to remain on the ground into the daylight hours, when they could be seen by locals.

Kanoos island.Image: Simona Foltyn

One such operation took place in April of last year, on the seam between the Arab and Kurdish areas of Iraq. A convoy composed of American and Iraqi special forces left the K1 Air Base in Kirkuk that evening, driving along unlit country roads, until it reached a checkpoint southeast of Kubaiba. The village had been a front line in the battle between Kurdish Peshmerga fighters and the Islamic State. Its civilians fled during the fighting and never returned. Even after the militants were officially cleared from the area in 2017, sleeper cells remained behind, using the abandoned village as a launchpad for attacks on nearby checkpoints and villages. They also dug tunnels that allowed them to retreat to the mountains when necessary.

The convoy of some 15 vehicles stopped at the checkpoint, according to Muhannad Saleh, a soldier with the tribal PMF who manned the post that night. (The PMF is Shiite-led, but it includes Sunni factions that draw fighters from local tribes.) Nine were black Humvees belonging to Iraq’s Counter Terrorism Service, and six were sand-colored M-ATV vehicles used by U.S. special forces. Part of the convoy remained near the checkpoint, while the rest moved north toward Kubaiba. According to an Iraqi officer with knowledge of the raid, the cars first stopped near Muzerir village, a mile east of Kubaiba. Both American and Iraqi soldiers filed out of the vehicles, moving in tandem as they searched house after house. When they found no one, the ground force commander made the fateful decision to continue on foot toward Kubaiba, perched further uphill. They walked for several hundred yards when a group of Islamic State members opened fire from a nearby house. The soldiers had no immediate backup from the gunners atop the vehicles—which had been left behind. Coalition aircraft were hovering above, but the ground troops’ formation had broken down, making it impossible to call in a precision airstrike without risking friendly fire.

- “When the tensions between the U.S. and Iran increased, the frequency of the raids went down in this area, and ISIS activities went up.”

For two hours, Saleh could hear heavy gunfire, and soon, reports of casualties: Two Counter Terrorism Service soldiers died, and four others were wounded. Up to 12 members of the Islamic State were killed in the raid. The forces remained in the area until 7 a.m. “Usually, when the Americans do missions, they don’t let the sun rise, because they want to withdraw,” Saleh told Foreign Policy. Shepherds woke up to the surprising sight of American and Iraqi troops driving past their houses.

The coalition, which usually shares updates on anti-Islamic State operations with media, published no details of the April 19 operation. In an emailed response to a question about the raid, the coalition confirmed that two U.S. troops and a translator were injured as a result of enemy fire.

The U.S. forces incurred casualties in at least one other raid in 2019. On Aug. 10, Iraq’s SWAT teams from Nineveh province together with American and Canadian special forces launched an operation to clear a forest-covered island in the middle of the Tigris River, near the village of Kanoos.

While Canadian special forces set up sniper and surveillance positions, the Americans alongside the Iraqi SWAT teams boarded boats and crossed the river to the island, according to local security forces based near the river shores. A member of the SWAT described it as a difficult operation, with the Islamic State using the network of tunnels it had dug underground to ambush the forces from behind as they tried to clear the island.

The firefight lasted for around two hours, claiming the lives of Gunnery Sgt. Scott Koppenhafer and a U.S. military contractor. Another U.S. service member and two members of the SWAT were wounded by enemy fire, according to a coalition spokesperson. After the casualties were evacuated, aircraft continued to shell the island until evening hours, wounding at least one civilian.

Grenade casings found on the shores of the Tigris river facing Kanoos island, where an American armored vehicle reportedly fired off rounds in direction of the island. A weapons expert identified the casing as 40mm grenades, fired from an auto grenade launcher like a MK19. Image: Simona Foltyn

Civilian casualties appeared to be an exception in these operations, but while carrying out an air raid on the village of Dub-Al Kabir in April 2019, a U.S. aircraft shelled a nearby federal police checkpoint. The friendly fire incident killed Sajad Musa Al Shameri and injured two other police present that night. The U.S. led coalition didn’t reply to a request for comment on the incident.

Abdallah Ibrahim Khalaf, a shepherd whose house was targeted in the Dub al-Kabir operation, told FP that he woke up to the sound of helicopters flying low. Iraqi forces assaulted his house, blindfolding and handcuffing Khalaf, his son and nephew. They were brought outside before an American soldier, who led the questioning during the interrogation (their blindfolds were temporarily removed). The soldier, speaking through an interpreter, asked him about the presence of Islamic State fighters. All three were released the same night. When FP interviewed him weeks later, Khalaf had left the village to live in Kirkuk city, citing fear from the Islamic State.

The secrecy surrounding these raids is to some extent inherent in special operations. But the Americans’ low profile also points to the increasingly tenuous position of U.S. troops in Iraq—a country now caught in the tug-of-war between the United States and Iran.

Soldiers from the Sunni Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) at their base overlooking Kanoos island.Image: Simona Foltyn

The coalition faced growing restrictions on the use of Iraqi airspace in the second half of 2019, after several mysterious blasts hit weapons depots and bases belonging to the Iran-backed PMF. No one claimed responsibility, but the PMF accused the United States and Israel of targeting its positions and pressured the Iraqi Joint Operations Command to impose greater restrictions on American surveillance drones and aircraft. The United States denied any involvement.

“When [the joint operations] were allowed, they were effective. But there were so many times that they were not allowed. Already in 2019, we were facing significant reduction of access,” said Michael Knights, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, who specializes in military affairs and who has advised the U.S. military in Iraq.

Throughout 2019, the Iraqi government expanded so-called Restricted Operating Zones to areas where Iran-backed armed groups were based, including areas around Baghdad and Diyala provinces where the Islamic State was active. Flying over these areas required special approval. “Sometimes they’d say yes, sometimes they’d say no,” a senior coalition official said, requesting anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the issue.

American ground forces faced similar movement restrictions. An Iraqi officer who has partnered with U.S. special forces to conduct anti-Islamic State operations said that the so-called Islamic resistance—PMF groups particularly hostile toward the United States—repeatedly prevented convoys composed of both Iraqi and American troops from accessing targets in their areas of control, even though the missions had been approved by the Joint Operations Command.

- Conversations with dozens of civilians and security forces suggest that the direct involvement of U.S. ground troops was a regular occurrence in 2019, with several such raids conducted per month.

In one such instance north of Baghdad, the Iraqi officer went to speak with a commander from the PMF’s Badr Organization to negotiate the convoy’s passage. “He told me, ‘This is our sector and we welcome you to conduct your operation. You are Iraqi and we are Iraqi. But honestly, we will not allow American forces to enter, even if you have the approval from the prime minister himself,’” the Iraqi officer recalled the Badr commander saying. In at least one instance in 2019, the PMF fired at a convoy composed of American and Iraqi special forces.

To avoid hostilities, Joint Operations Command has at times nixed operations with an American ground component near PMF areas. Now, mounting threats by the so-called Islamic resistance to strike against American targets to avenge the deaths of Suleimani and Muhandis have further raised the risk of confrontation, making U.S. participation in such operations increasingly untenable.

“The situation will be more difficult in terms of conducting our missions,” said the Iraqi officer who regularly partners with American special forces. Asked if he could do without them, he answered: “We can achieve victory, but we will bleed more.”

Coalition officials, often frustrated at Iraq’s unwillingness to rein in the PMF, say that the pause in coalition activities may be a natural opportunity to wean Iraqi partners off of U.S. support. “In the near term, there is a reduction in the effectiveness of those operations,” said a senior coalition official. “But in the long term, the whole purpose of this is that it’s only Iraqis securing their country against ISIS.”

But civilians in rural areas have watched Iraqi security forces struggle to effectively fight the insurgency.

Since 2018, the rural areas around Kirkuk have witnessed several large-scale military operations by the Iraqi Army and police to clear sleeper cells. Military commanders declared these operations a success, but civilians say the militants would hide while operations were underway, only to reemerge days later and resume their campaign.

- “In the long term, the whole purpose of this is that it’s only Iraqis securing their country against ISIS.”

In 2018, Riyadh district was one of the most dangerous areas in Kirkuk province. Farmers feared venturing beyond the small group of mud houses to tend to their fields. Shepherds rarely reared their sheep past sunset, a dangerous time of day, when Islamic State militants would emerge from their hideouts in nearby riverbeds and caves. Traffic along the main road was sparse, with drivers wary of fake checkpoints the militants occasionally set up to kidnap civilians and of the IEDs they planted overnight to target early morning commuters. Villagers didn’t sleep at night, instead taking turns atop their rooftops to keep an eye on a group of Islamic State fighters who freely roamed the villages in search of material support

But then, intelligence-led raids conducted by U.S. and Iraqi special forces, coupled with police deployment deeper into rural areas, turned the tide.

“When the raid happened, it broke their back,” said Ayad Mutashar, who lives near Nasr village in Riyadh district, just a few miles west of Khatuniya.

One night in December 2018, villagers woke up to the sound of helicopters. A column of humvees, lights out, approached from the main road, with loudspeakers calling on people to stay inside and asking the militants to surrender. One landed to drop troops, while the other one hovered above. For a while, the sound of gunfire echoed across the plains, and after two hours, the helicopters left, leaving behind the bodies of two Islamic State fighters. The operation was carried out by the second brigade of Iraq’s CTS and U.S. Special forces based in Kirkuk. It was carried out by the second brigade of Iraq’s CTS and U.S. Special forces stationed in Kirkuk.

But in March this year, American troops withdrew from the K1 Air Base in Kirkuk. The joint operations have largely ceased, leaving the villagers once again vulnerable to the Islamic State.