In January 2017, Rosalie Downing was admitted to Mountain View Health & Rehabilitation, a low-slung nursing home with four wings in El Paso’s Golden Hill neighborhood. Rosalie had kidney disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes. She used a wheelchair and needed help using the bathroom, bathing, and getting into bed. Her son, Charles Downing, made the tough decision to put her in the nursing home, one recommended by her physician.

“She was getting dementia,” Charles said. “She wasn’t able to take care of herself. She was waking up two or three times a night.”

One November morning in 2018, Rosalie fell when a nurse tried to move her from the bed to her wheelchair. She fractured her right arm and hip and was in severe pain. Charles got a phone call from the nursing home and rushed to the facility, but Rosalie had already been sent to the hospital for surgery.

She died four days later at the age of 87. An inspector later determined that Rosalie’s nurse failed to follow “proper and safe” transfer procedures, resulting in blunt force injuries that contributed to her death.

Mountain View Health & Rehabilitation was acquired in February 2018 by Creative Solutions in Healthcare, a company that owns and operates 64 facilities in Texas and is the state’s second-largest nursing home owner.

At the time of Rosalie’s death, nine months after Creative Solutions took ownership of the facility, Mountain View was short-staffed. It received one out of five stars on the staffing rating provided by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), operating with 40 percent fewer registered nursing staff than its residents needed. Charles, who visited his mother every morning, said she sometimes waited 20 minutes for someone to answer her call light when she needed to use the bathroom.

“[Nurses] said, ‘Well, I’m with another patient. I can’t just leave the patient and hurry to the bathroom,’” Charles said.

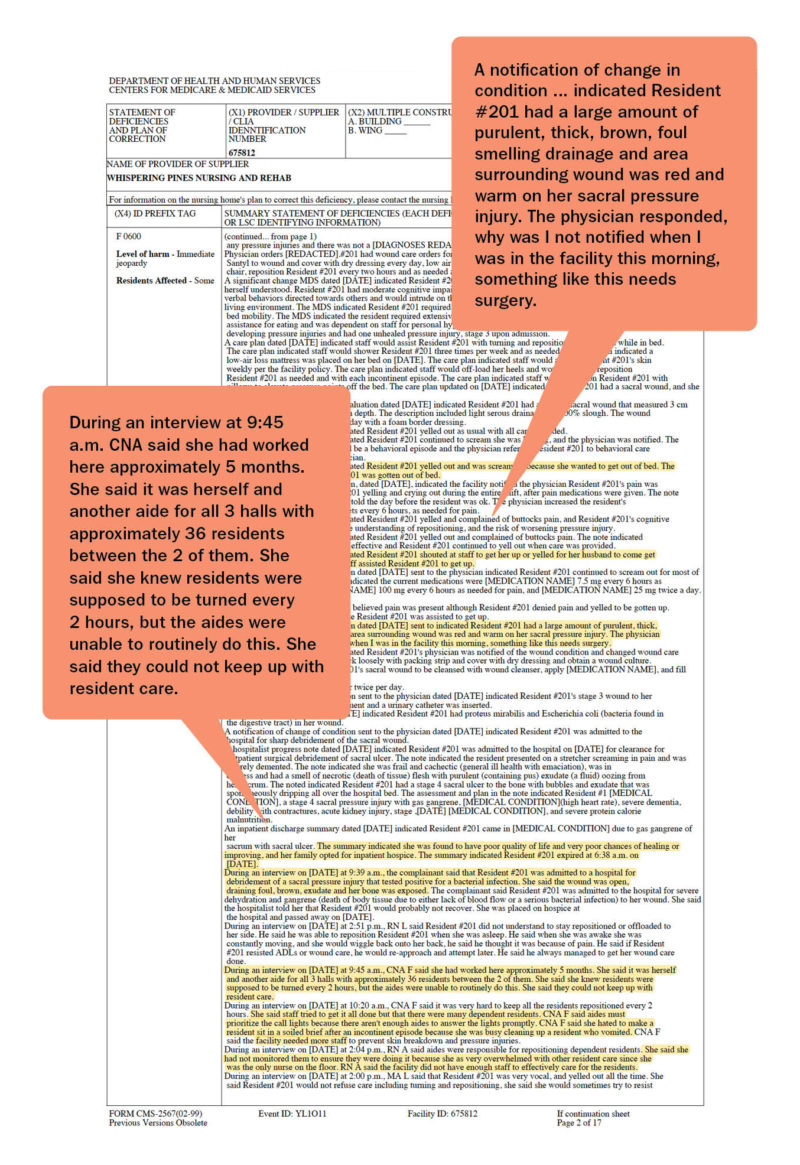

A Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) inspection report from a survey completed on May 9, 2019.Image: ILLUSTRATION BY DRUE WAGNER

In Texas, corporate-owned homes like Mountain View serve over 76,000 people—83 percent of the state’s nursing home residents. Long before the coronavirus spread with devastating consequences through these facilities, residents were getting injured and dying from inadequate care, lending Texas the dubious distinction of being one of the most dangerous states in the country to be a nursing home resident. Since 2015, more than 1,800 dangerous incidents, categorized as “serious deficiencies,” have been reported to federal regulators from Texas—more than in any other state. New York, the state with the most people in nursing homes, had 162. In the past five years, at least 143 people have died due to neglect and poor quality of care in Texas nursing homes.

“Abuse has more headlines, but neglect has more victims,” said J.T. Borah, an Austin-based nursing home abuse and neglect lawyer. “What you end up with is too few people spending their whole shift putting fires out, as opposed to actually managing the care they’re supposed to be giving to the residents.”

Neglect, which is defined by the state as the failure to provide medical services necessary to avoid physical or emotional harm or pain, accounts for the vast majority of deaths, and, along with abuse and exploitation, is a top cause for serious deficiencies in Texas nursing homes. This includes staff failures to provide CPR, prevent falls, monitor lab results, or report changes in a patient’s condition to physicians.

Over the past year, the Texas Observer and Type Investigations analyzed tens of thousands of federal inspection reports, examined staffing ratios of more than 1,200 facilities in Texas, and reviewed four years of federal penalty data. The analysis found that nearly all of the for-profit corporations operate nursing homes well below the thresholds for adequate staffing determined by federal regulators. A review of inspection reports shows that many deaths and serious injuries are related to low staffing levels—a problem our analysis shows is particularly acute in the state’s for-profit nursing homes. Experts around the country have repeatedly found that corporate owners cut staff hours to increase profits, leaving residents at increased risk. Texas has, on average, the lowest staff-to-patient ratio in the country.

Image: Andrea Ucini

Gary Blake, Creative Solutions’ president and cofounder, said in a statement that administrators and staff at each of its facilities are held to the highest standards, working diligently to provide the tools necessary to ensure the staff receive ongoing training. “The unexpected loss of someone in our care is a devastating event,” Blake said. “We will launch an internal investigation after any state inspection that results in an unacceptable finding and appropriate measures will follow.” Creative Solutions declined to answer specific questions about Rosalie Downing’s death.

At the same time, companies owning problematic nursing homes continue to operate and grow with relative impunity. Fines from regulators amount to a tiny fraction of their annual revenues; a lawsuit reform bill passed by Texas legislators in 2003 arbitrarily capped damages for families seeking justice through the courts, disincentivizing lawsuits against nursing homes. Even when a nursing home operator is sued successfully, it can hide its assets, making it nearly impossible for families to collect judgments.

“There is virtually no downside to them drastically cutting back on staffing and killing people because they will be making money,” said Ernest Tosh, a Texas nursing home neglect lawyer. “The state isn’t going to fine them very much, if at all. So why wouldn’t you do that if you’re a nursing home?”

In Wills Point, a small city east of Dallas, a diabetic nursing home resident couldn’t eat or talk for seven hours in 2018 when his blood sugar dropped dangerously low. He was eventually found on the floor without a pulse and died a few hours later. Last year in Southlake, a 98-year-old woman had a urinary tract infection, but lab results fell through the cracks. Her infection drastically worsened four days after the lab results came in. Another woman in Winnsboro waited 17 days for treatment of an infected pressure wound in her pelvis. By the time she got to the hospital—screaming in pain—the wound had developed gangrene, dripping a large amount of “thick, brown, foul smelling” discharge. With poor chances to recover, her family opted for hospice, where she later died.

Each of these residents lived at for-profit facilities. The conditions under which these residents died were documented by state inspectors, tasked with investigating all nursing home deaths. In Texas, the Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) conducts annual inspections, along with investigating facilities’ self-reported incidents and complaints filed by family members or residents. Incidents involving harm or death must be reported by nursing home facilities to HHSC. But advocates and lawyers said facilities sometimes fail to report, so when a family does not file a complaint, or a resident has no family, incidents involving harm or death may go unchecked.

When elderly or disabled Texans can’t take care of themselves, they can opt to live at a nursing home that’s either for-profit, nonprofit, or run by the state. For-profit homes accumulated 23 percent more federal violations per capita than nonprofit homes, and investigators substantiated about 70 percent more complaints from families; of the 143 people who have died in Texas nursing homes due to poor care and neglect since 2015, 120 lived in for-profit homes.

Using payroll records, CMS rates each facility’s staffing from one to five stars. More than half of Texas nursing homes have a one-star total staffing rating, the highest number in the country. The shortage of registered nurses, the highest-trained nurses responsible for managing care and supervising staff in these facilities, is even more stark—58 percent of Texas homes received a one-star rating for registered nurse staffing, the second worst after Louisiana.

Federal minimum staff-to-patient ratios do not exist, but CMS does require facilities to have a registered nurse on-site eight consecutive hours a day, seven days a week, with a few exceptions. In 2019, more than half of Texas nursing homes reported no registered nurses on their payroll at any given point. Texas does have minimum staffing ratios in place. But the standard is so low as to be essentially meaningless, requiring only 0.4 licensed care hours per day, or one licensed nurse for 20 residents. By this standard, all facilities in Texas were, on average, adequately staffed in 2019.

Nursing homes need different levels of care depending on how frail their residents are, so CMS adjusts the staffing data based on the needs of each facility’s residents. Using the adjusted staffing data, we found that for-profit nursing homes in Texas were more likely to operate with low staffing levels than those run as nonprofits. In 2019, there was, on average, one registered nurse for every 35 residents at nonprofits, one registered nurse per 70 patients at government-run facilities, and one for every 77 residents at for-profit homes.

Creative Solutions operated with, on average, one registered nurse for every 98 residents in 2019.

Patrick Woodson, a Fort Worth-based lawyer who has worked on nursing home cases for more than 20 years, said the rampant inadequate staffing stems from for-profit corporations squeezing “every penny they can out of operating these facilities at the detriment of the residents.”

“They have them laying in their own waste because [nurses] don’t come by enough because they’re understaffed. They get pressure sores and they get infected. They go into septic shock, and it’s just flat-out neglect,” Woodson said.

Mountain View, Rosalie’s facility, decreased its registered nurse staffing ratio by 46 percent the year after it was acquired by Creative Solutions. The facility’s corresponding CMS rating dropped from two stars to one in 2019.

In a statement, Creative Solutions’ Blake said the company invests deeply in each of its facilities. He said that in some cases, raising the standard of care within a newly acquired facility requires changes in staff, which can create short-term challenges.

The state inspector who documented Rosalie’s death described another incident in the same report: A 57-year-old woman was found on the floor screaming—she had a laceration on her chin and a “large purple, red and green bruise to her right eye” from an earlier fall two days before. It was her fourth fall in less than four weeks. According to interviews with nurses, the evening and weekend shifts were operating with only two certified nurse aides—employees who help residents take showers, change soiled briefs, and participate in daily activities.

“[Nurse aide] said on weekends and evenings with less staff you cannot monitor the residents frequently, so more accidents and incidents happen,” the inspection report said. The resident fell one more time after that, found on the floor naked with large dark purple bruises on her left hip and side and her entire back.

The nursing home industry blames low Medicaid reimbursement rates for staffing shortages. Kevin Warren, CEO of the Texas Health Care Association, said low reimbursement rates in Texas—which are among the lowest in the country—prevent facilities from improving staffing levels or increasing wages. “Our current average Medicaid rate is almost $50 per day less than the national average Medicaid rate,” he said. “The last rate increase for Texas nursing facilities was almost 10 years ago.”

Image: Andrea Ucini

Blake said that hiring and retaining well-qualified health care providers has been Creative Solutions’ top priority, but it is an industrywide challenge, particularly in Texas.

“The robust economy we have enjoyed, coupled with a relatively low Medicaid reimbursement, makes competition for qualified workers especially difficult in some of the communities we serve,” he said.

Facilities can get additional reimbursement through two state programs. One gives providers more Medicaid money to hire more workers, which provided an estimated $91.5 million to 962 nursing facilities in fiscal year 2020. Another program boosts Medicaid payments to facilities that improve on quality metrics, with funding dedicated to improving recruitment and retention of staffing and increasing the number of daily registered nurse hours in facilities. More than 800 facilities received $66 million in fiscal year 2020 from this component.

David Grabowski, a Harvard Medical School professor, agrees that low reimbursement rates are the main reason facilities are unable to staff at adequate levels. But companies still need stronger oversight, he said. “If Texas were to increase reimbursement, a concern by a lot of advocates is whether those dollars actually find their way to direct patient care,” Grabowski said.

Texas lawmakers have tried to pass bills in the past two legislative sessions to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates in an effort to improve nursing home conditions, with no success. Patty Ducayet is the state’s long-term care ombudsman—she heads an independent office connected to HHSC that advocates for residents’ rights. Ducayet said that these efforts do not create safeguards so that state dollars actually support staff wages, health care benefits, and sick leave.

“With these corporate-owned facilities, where does the money go if we increase rates? The only way to improve care is to ensure the money doesn’t go into their pockets,” she said. Some facilities are “literally competing with fast-food restaurants” when it comes to nursing wages. In San Antonio, the average hourly wage for a nurse aide is $11, according to Cindy Boyum, a local ombudsman.

And although Medicaid reimbursement rates are low, so is the cost of doing business in the state. Poor staffing is “related in part to business decisions that these operators are making, and I’m very concerned it might be related to squeezing profits out,” Ducayet said.

In addition to citing noncompliant facilities, HHSC can recommend federal fines, suspend new admissions to facilities, and revoke or suspend licenses based on inspectors’ findings. While serious deficiencies, which can result in a financial penalty, have dropped by more than half since 2016, HHSC reported that it investigated a “substantially higher number of complaints” from 2013 to 2018, leading advocates to wonder if serious deficiencies are being undercounted.

Robyn Grant, director of public policy at advocacy group National Consumer Voice, said her team has seen cases of death, broken bones, and serious hospitalizations not categorized as “serious deficiencies,” or an immediate jeopardy to a resident’s health or safety. Classifying these incidents as serious is “critical because that drives the enforcement system,” Grant said. “You do not have meaningful penalties until you have harm.”

In 2017, President Trump rolled back Obama-era regulations that fined facilities for each day they were out of compliance. Now they are fined only once per violation. During the first quarter of 2019, the state’s average fine for a nursing home deficiency was $41,296, down from $62,431 in 2017.

“The nursing home industry pushed aggressively for that change,” Grant said. “It [shows] the power of the industry and, quite frankly, an administration that has a deregulatory philosophy and an approach to doing things that help business owners.” Creative Solutions, which reportedly had $282 million in revenue in 2018, was fined $56,618 in 2018 for more than 300 deficiencies in Texas nursing homes that year.

Elliott Sprehe, a spokesperson for HHSC, said that penalties are assessed on a case-by-case basis. The agency’s considerations are based on the facility’s compliance history as well as whether a pattern exists, the violation is recurring, or the violation presents a danger to resident health and safety. The penalty’s amount depends on the potential hazard to residents and the facility’s efforts to correct it, Sprehe said. “Our top priority always remains the health and safety of staff and residents in all the nursing and assisted living facilities throughout Texas,” Sprehe said in a statement.

Of the 40 deaths in 2019 identified by the Observer and Type Investigations, Texas facilities were fined by CMS, on average, $15,549 per death.

The state also has the power to impose fines, but HHSC issued just three fines in three years.

Worse still, residents and their families cannot appeal the decision if state inspectors do not substantiate a complaint of neglect or abuse. Meanwhile, facilities can dispute deficiencies to change their scope of severity or remove them. They can also appeal enforcement actions.

The so-called Three Strikes Bill passed in Texas in 2016 required HHSC to revoke a facility’s license if the provider had committed three serious deficiencies in two years. But in 2018, the state reported that 15 facilities with one or more strikes simply changed ownership, so their strike count went back to zero. Ten facilities cleaned their record after appealing.

Despite their terrible staffing rating and documented pattern of serious safety violations, Texas nursing homes are substantially protected from medical malpractice litigation. In 2019, AGRC, a risk management company, released a report saying that Texas was among the states with the lowest “loss rate”—the annual amount of money, per bed, spent by long-term care providers to defend, settle, or litigate claims in a year. The state’s projected loss rate in 2020 is $670, far below the national projection of $2,300. That’s largely because in 2003, the nursing home industry lobbied zealously to keep malpractice awards at $250,000, the lowest malpractice cap in the country.

“They can have pressure sores all over their body. They can have maggots in their pressure sores, they can have flies flying around them, and they can lay there and rot to death. And the max you could get is $250,000,” Woodson said.

“They’re not going to change their staffing for that; that is nothing,” said Tosh, the abuse lawyer. “That is the cost of doing business in Texas.” And since bringing these cases to trial is often so expensive, he said, even the maximum award can be consumed by legal and expert fees.

Plaintiffs attorneys face additional challenges trying to collect awards. Many nursing home owners use obscure ownership structures to hide their assets—if they do get sued, they can claim their reserves are too low to pay out.

According to lawyers who have worked in nursing home litigation, corporations that own nursing homes, like Creative Solutions, typically fracture their operations into various obscure “single-purpose entities,” each designated to offer various services to their nursing homes. For instance, a company might create a real estate company, a therapy company, an insurance company, and a pharmacy. They then require each of their homes to transact business with their own entities at rates above market rate, allowing the owners to siphon profits into related companies while showing no assets. A 2013 study by Grabowski and other Harvard Medical School researchers revealed that Texas companies have increasingly relied on this method to obscure their finances.

Nursing homes in Texas are also not required to be insured. Tosh said facilities sometimes buy a “wasting” policy, so that the cost of the defense comes out of what is often only $100,000 in coverage to avoid paying much in the event of a lawsuit. The more work defense attorneys do for a case, the less money will be left for paying a settlement.

“I am aware of a situation in which the defense attorney informed the plaintiff’s attorney that all that remained of the $100,000 policy was $20,000 and that was all they would ever offer the family of a resident who died due to negligence of the nursing home,” said Borah, the Austin-based attorney, in his testimony to the Texas House Human Services Committee in November 2018.

With low chances of success in the courts, family members are usually left with no other options as they deal with the pain of losing their loved one under conditions that often lead to slow and painful deaths. In the meantime, facilities continue to operate, sometimes without being fined.

State inspectors cited Mountain View after medical records showed Rosalie Downing’s fall contributed to her death. But no fine was issued. Charles Downing recalled his frantic dash to the hospital when he got the call from the facility about her fall. Doctors inserted pins to hold the fractures in position until her bones healed. But her body couldn’t take the weight of surgery. She died at 4:21 a.m. on a Monday.

“She wouldn’t have passed away other than this happening,” Charles said.