In September, 2016, Bratton stepped down as commissioner, and O’Neill took his place. Latrice Walker, who represents a district that includes Brownsville in the New York State Assembly, spoke warmly of O’Neill, who grew up in East Flatbush; there was a “human element” to him, she told me. But some within the department had reservations. “He’s a bridge-builder,” a former police chief explained. “But he doesn’t keep very good company, and that’s a big failing of his.” To fill two of the department’s most influential roles, O’Neill turned to Dermot Shea and Terence Monahan. They had all been commanders in the Bronx, they all belonged to the N.Y.P.D.’s Emerald Society, a fraternal order of Irish-American cops, and they were all closely associated with the tactics ushered in by Bratton.

Shea, whom O’Neill picked to be the chief of detectives, previously led the Forty-fourth Precinct, near Yankee Stadium. At the height of stop-and-frisk, his officers used force during stops more often than in any other precinct in New York, according to data reported in the Times. Monahan, whom O’Neill made the chief of department, had spent years overseeing precincts in the Bronx. He “personified” the department’s stop-and-frisk policy, according to Warner Frey, a retired Transit Bureau captain who worked in the Bronx. At CompStat meetings, Monahan would push cops to write more stop-and-frisk reports and quality-of-life summonses. Every officer in a patrol unit was judged by how many of these reports they produced, which led to “unnecessary confrontations between police and citizens,” Frey told me. “It was all about getting numbers,” he added. “There were plenty of people like Monahan, and they all wanted to carry out this policy, because that’s how you got promoted.” (The department disputes this, and said Monahan does not believe that the number of summonses or arrests is a measure of success.)

One of Craig Edelman’s closest connections within the top brass was Charles McEvoy, a deputy chief. Edelman and McEvoy first met in 2004, while on duty at the Republican National Convention. Banks, who then supervised McEvoy, considered him a “very conscientious officer.” In 2012, when the N.Y.P.D. recorded more than half a million stops, McEvoy led the 103rd Precinct, in Jamaica, Queens; Edelman, as one of his sergeants, earned a collection of awards from the department. Martin Zuniga, a lieutenant in the precinct, recalled that Edelman was a “very active” worker, the type who would race to every crime scene and stay up late doing paperwork. McEvoy, he said, was a good boss, exacting but fair.

Not everyone felt that way. In 2010, Clifford Rigaud, who by then had worked at the 103rd Precinct for six years, recorded a meeting with McEvoy after receiving what he felt was an unfair performance review. McEvoy, who is white, criticized Rigaud, who is Haitian-American, for arresting only four people that year. In the N.Y.P.D., McEvoy told him, “a lot of what you’re evaluated on is activity by numbers.” He added that he tried to instill this lesson in all of his sergeants and lieutenants. “I always tell them personally, ‘Everything’s all about numbers, numbers, numbers.’ ”

Rigaud told me that the pressure to deliver numbers caused cops and commanders to lose their “moral compasses.” Rigaud’s former partner Michele Alexander agreed. “If there is no crime, you make the crime,” she said. In 2015, Alexander and another cop, Jazmia Inserillo, both of whom are Black, received six-figure settlements after claiming, in separate lawsuits, that one of their supervisors, Jason Margolis, sexually harassed them. Both women told me that Margolis, who is white, was a particularly aggressive presence on the streets of Jamaica, which is predominantly Black. “He would stop people for no rhyme or reason,” Inserillo said, “and he had us doing the same thing.” (A legal representative for Margolis did not respond to a request for comment.)

According to Inserillo’s lawsuit, McEvoy insisted that Margolis was an “asset to the command,” and refused to assign Inserillo to a different supervisor. McEvoy generally gave preference to his white subordinates, she told me. Edelman, she added, was one of his favorites. (The department disputes these claims. Edelman told me he didn’t see discrimination at the precinct, and added that he worked closely with a Black officer.)

By 2013, Edelman had left Queens and was working as a lieutenant in Brownsville. His duties included supervising rookies in a program called Operation Impact, which flooded blocks that the department had identified as “high-crime” with recruits fresh out of the police academy—a centerpiece of the department’s stop-and-frisk strategy. The following year, Bratton announced that he would reform the program. He branded the department’s new strategy “precision policing,” which he defined as an attempt to pinpoint “the small cohort of actors” who “perpetuate a vastly disproportionate amount of the city’s violent crime.”

Edelman was positioned at the forefront of this undertaking. By 2017, he had become the head of a unit that investigated gang activity in Brooklyn. The N.Y.P.D. had built a database listing thousands of suspected gang members, virtually all of them Black or Latino. Investigators were instructed to follow young people on Instagram or play video games with them online, posing as teen-agers. If a kid bragged about some dubious exploit, or even “liked” such a boast, he risked getting listed in the database. Edelman and other gang investigators would build cases against dozens of suspects at a time, but the Brooklyn D.A.’s office eventually tossed many of the cases out. “People who live in public housing know that there are a couple bad apples doing the shootings and the robberies,” Eric Gonzalez told me. “They want us to deal with them, but they really don’t want us to ensnare every young person who likes something they put on their social-media page.”

In the fall of 2018, Brownsville saw a spate of shootings. At CompStat meetings, Edelman was able to recite the names and aliases of alleged gang members, describe their rivalries and “territories,” and explain how his anti-gang unit was investigating them. “He was very good at the podium because we had mentored him,” Lori Pollock, a retired chief who co-chaired the meetings, told me. “And given his connections,” she added, “there was no doubt that he would go farther.” At the time, McEvoy served as second-in-command of Patrol Borough Brooklyn North. When the position of commander opened up at the Seven-Three, Edelman took over. Monahan, as chief of department, likely approved the move. According to several chiefs, this was a mistake. “Edelman is a good soldier,” Pollock said, “but he wasn’t the logical choice to perform community outreach.” Monahan, she said, “put him in a bad position.” (Monahan couldn’t be reached for comment.)

In February, Edelman spoke with me by phone, from police headquarters, in the only interview that he has given since the previous summer’s protest at Barclays. He declined to talk about the incident, but described feeling a sense of duty toward what he referred to as Brownsville’s “silent majority”—the “great people that aren’t committing the violence.” He claimed that he got along with some gang members, too, many of whom he’d known for years. “We would crack jokes, and they were appreciative of the police being on post,” he said. “It sounds bizarre, but it’s true.”

When Edelman took over as commander of the Seven-Three, he said, a number of local gangs were engaged in “historical beefs.” He stationed cops on blocks where shots had been fired, and directed his anti-crime team to get more guns off of the streets. Only one other Brooklyn precinct, the much larger Seven-Five, which contains East New York and Cypress Hills, made more arrests for gun possession in 2019. Meanwhile, according to data reported in The City, officers in the Seven-Three self-reported a thirty-three-per-cent increase in the use of force that year; sixty of these incidents resulted in civilian injuries. The Civilian Complaint Review Board received a hundred and forty-eight complaints, about a quarter more than the year before.

Gonzalez told me that this style of policing eroded trust in the criminal-justice system, discouraging witnesses and victims from coming forward with information about crimes. He also said that Edelman’s gun arrests often failed to meet constitutional standards. In some cases, officers had neglected to turn on their body cameras, or had engaged in what Gonzalez regarded as racial profiling. “People were getting stopped for jaywalking or spitting,” he said. “You just don’t see that in Park Slope.” Gonzalez, who grew up near Brownsville, refused to pursue many of these cases. In the year before the summer of 2020, the Seven-Three accounted for seventy-nine of the gun cases that Gonzalez’s office declined to prosecute. No other precinct in Brooklyn accounted for more than fifty-five. Disagreements between police and prosecutors over these arrests “became more and more personal,” Gonzalez said. One argument with Edelman left an Assistant District Attorney in tears. (Edelman says he was never involved in such an encounter.)

In a series of closed-door conversations, Gonzalez and N.Y.P.D. representatives, led by Monahan, tried to talk through their differences. Officials from the Mayor’s office acted as mediators. They went over the disputed gun cases one by one. “In the overwhelming majority of cases, we stood by our decision,” Gonzalez said. Still, he added, Monahan remained adamant that Edelman was “doing a fantastic job of getting guns off the street.”

In the summer of 2019, Brownsville experienced another surge of gun violence. At a public briefing on crime statistics, Monahan laid the blame on Gonzalez, complaining that people arrested for gun possession were seeing “little or no jail time.” One of Gonzalez’s new policies allowed defendants who had never previously been arrested for violent crime to participate in violence-prevention programs instead of going to prison. Gonzalez, who lost a brother to gun violence, didn’t think that locking such defendants up for a few years would make the community safer. At the briefing, de Blasio joined Monahan in criticizing Gonzalez’s approach. “The N.Y.P.D. has been doing amazing, amazing work,” he said. “They need the prosecutors to be just as aggressive.”

As shootings rose, Edelman began requiring his officers to work longer hours, causing the precinct’s overtime costs to soar. Earlier in the year, Governor Andrew Cuomo had made changes to the state budget that threatened to deprive the city of six hundred million dollars. De Blasio, in turn, had warned every city agency that they would need to make sacrifices. But, by the end of the year, the N.Y.P.D. had exceeded its projected overtime budget by some fifty million dollars. When Fausto Pichardo, the chief of patrol, learned about Edelman’s spending, he was “livid,” a former department official told me. Pichardo was four ranks above Edelman in the chain of command, and, after looking into the Brownsville community’s complaints about Edelman, he determined that the commander should be removed from his post. After he asked to talk it over with Monahan, his request to transfer Edelman was denied. (Pichardo, who retired a year later, did not respond to messages seeking comment.)

Some in the community supported Edelman. Viola Greene-Walker, the district manager of Brownsville’s community board, told me that residents often e-mailed her to complain about people drinking and selling drugs right outside their homes. “You don’t have many people who will publicly speak up,” she said. “They fear retribution from their neighbors.” But Latrice Walker, the Brownsville representative in the State Assembly, told Edelman that the constant surveillance and harassment made many of her constituents feel unsafe. At one point, after a drive-by shooting, Edelman stationed a patrol car on Mother Gaston Boulevard, a busy commercial strip; it sat in the middle of the street day and night, isolated from the community by a lane of traffic on either side. Walker encouraged Edelman to let his officers walk around and talk to people, warning him that there would be “some type of blowup” if he didn’t ease tensions on the block. “I talked with him ad nauseum about it,” she told me. “He just disregarded it, like I didn’t know what I was talking about. And it got to the point where someone died.”

Latrice Walker, who represents Brownsville in the State Assembly, warned Craig Edelman that there would be “some type of blowup” if he didn’t ease tensions in the neighborhood.Image: Dawit N. M.

In October, 2019, on the stretch where Edelman had installed the patrol car, two officers tried to arrest a young man inside a nail salon. As the man began screaming, Kwesi Ashun, a local T-shirt vender who happened to know him, ran inside. Ashun’s sister later told The City that her brother, who was thirty-three, had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and had an intense distrust of the police. In the nail salon, he started hitting one of the cops. The cops shocked Ashun with a Taser, which failed to subdue him, and he slammed an officer’s head with a metal folding chair. The officer, Lesly Lafontant, drew his gun and shot Ashun four times, killing him. Lafontant was hospitalized and placed into a coma.

After the incident, Walker spoke with Edelman’s superior, Jeffrey Maddrey, hoping that the department would move Edelman somewhere else. Instead, in November, Edelman was promoted to deputy inspector. McEvoy performed the traditional honor of pinning golden oak leaves to Edelman’s collar. Dermot Shea replaced James O’Neill as N.Y.P.D. commissioner a week and a half later. Monahan remained the chief of department, and soon tapped McEvoy to run his office. At a ceremony for Shea at police headquarters, a pipes-and-drums band played “The Dawning of the Day.”

At the event, Shea said that he hoped to find ways to keep young people out of jail. “I don’t want to see one more kid wander onto the road of getting arrested if we can do something better,” he said. A few days later, de Blasio spoke about this vision in even grander terms, promising to “create a bond between police and community and young people, in particular, that has literally never been seen.” “But to do that you need visionary leaders,” he added. “And you need leaders who are not afraid of change but, in fact, embrace it.”

On a summer evening in Brownsville last year, a community-outreach worker, who asked to be called by his middle name, James, sat on a bench along Mother Gaston Boulevard, not far from where Kwesi Ashun was killed. Halfway down the block, a dark stain on the sidewalk marked a spot where someone had been shot a few nights before. Like a cop on a foot post, James was watching the street, waiting for night to fall. Soon the kids whom he affectionately called the “knuckleheads” would come out. “What I try to do is help guys change their mind-set,” he told me. “Try to help them get jobs. Try to help them gain a different understanding of things.”

James, who was not authorized to speak with me by his employer, works for an organization that receives funding from the Mayor’s office. He was trained in Cure Violence, a public-safety program that deploys teams of “violence interrupters” to work intensively with young people—extricating them from feuds, attending their court hearings, introducing them to potential employers. In areas of New York where they operate, shootings have dropped by as much as seventy per cent. Many violence interrupters have deep ties to the streets. “I used to be known in the community as a tyrant,” James, who grew up in Brownsville, told me. To their supporters, their backgrounds make them “credible messengers,” but cops often disparage them as “perps.” James said that Edelman and his officers would often try to intimidate the young men who worked with him. “He knows who I am, but he still persists in antagonizing them,” he said. “It messes up the whole feng shui of the thing.” (Edelman told me that he supported the violence-interrupter movement and said that violence interrupters were “always welcome in the Seven-Three Precinct.”)

One day last May, as the pandemic continued to rage throughout the city, a group of families and friends gathered around platters of jerk chicken and rice and peas in the courtyard of a building that the police regarded as a gang stronghold. People were drinking and smoking weed. James and another violence interrupter were there to give out masks and “keep the peace.” At one point, someone called 911 to report a large crowd. Cops assembled in front of the building. Several officers climbed onto the roof. To James, it looked like they were “getting ready for war.” When a young man accused the police of invading their space, an officer threw him against a wall and charged him with disorderly conduct. Edelman, who had shown up on the block without a mask, told James that people had been disobeying the social-distancing order. “The pandemic was a cover,” James said. “He just wanted to lock a bunch of Black people up.” (When I asked Edelman if the police were genuinely trying to enforce the social-distancing rule, he acknowledged that it wasn’t a “primary concern.”)

The violence interrupters did have an ally in the Seventy-third Precinct. Edelman’s second-in-command, Derby St. Fort, was widely respected by Brownsville’s community leaders. He got to know many of them during the summer of 2019, after Arsenio Gravesande, an alleged leader of the Crips, was shot and killed in Brownsville. At a vigil on Gravesande’s block, dozens of officers in tactical gear lined up across the street from hundreds of mourners, many of whom were alleged Crips members. At several points, the police moved into the crowd, but St. Fort, who is Black, repeatedly stepped in. After telling the mourners to conceal their bottles or move their double-parked cars, he’d implore the cops to back away. In the end, no one was arrested or hurt. In an e-mail, St. Fort told me, “I always knew that something was wrong with how we policed, but until Arsenio Gravesande’s vigil, I didn’t realize that there was a solution.”

On Mother Gaston Boulevard, outside a nail salon where Kwesi Ashun was killed by police, in 2019, a team of violence interrupters now keep watch over the block.Image: Dawit N. M.

That fall, acting on his own initiative, St. Fort invited representatives of five community groups, the District Attorney’s office, and the Mayor’s office to meet with him every month. He began debriefing them on the precinct’s crime data, and dispatching teams of violence interrupters to blocks where shootings or robberies had occurred. In essence, St. Fort was building a small-scale replica of CompStat, the management system that Bratton had rolled out in 1994. But, instead of using statistics to incentivize stops and arrests, St. Fort was supporting residents’ efforts to reduce the need for law enforcement. “Community policing can work if you have a great leader,” Camara Jackson, the director of Elite Learners, a community organization that took part in the initiative, told me. “Anytime St. Fort said, ‘This is a problem block,’ we fixed the block. We told the cops, ‘Lay off of those areas.’ And it was successful.”

In the months after the meetings began, the Seventy-third Precinct reported only a handful of shootings, even though gun violence was increasing citywide. Brooklyn’s borough president, Eric Adams, who is a Brownsville native and a former cop, singled out St. Fort in a speech, declaring that he’d developed a “thought-provoking, innovative way of addressing crime.”

Edelman didn’t participate in these meetings. According to Jackson, several community leaders only agreed to attend after learning that he wouldn’t be there. “We didn’t want people to be discouraged,” she said. Within the Seven-Three, it largely went unspoken that the precinct was pursuing two opposing approaches to public safety: the community-led model that the department’s leaders publicly supported and the aggressive, top-down style that many of them actually practiced. “Unfortunately, violence interrupters were not viewed as legitimate by many of my peers,” St. Fort told me, in an e-mail. “I decided to lean on the community, even though it felt like a risk to my professional career.”

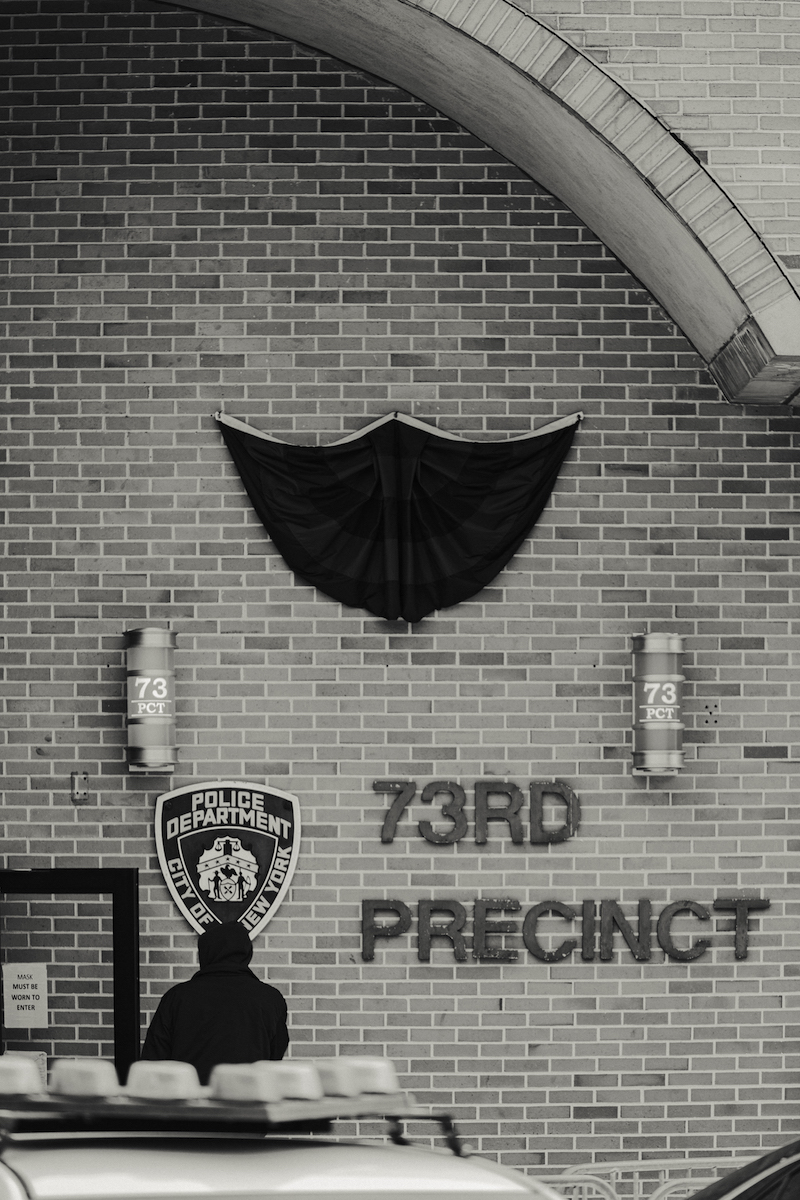

Only one other Brooklyn precinct made more arrests for gun possession in 2019 than the Seventy-third.Image: Dawit N. M.

In response to gatherings during the pandemic, St. Fort helped create a new protocol for social-distancing enforcement: the police would summon violence interrupters to hand out masks and talk to people, and only if this failed would the cops intervene. The strategy was launched on a sunny Friday last May. People who’d spent months trapped in overcrowded apartments filled the streets. The violence-prevention groups didn’t have nearly enough workers to cover every gathering. Soon Edelman and his men were striding down a residential block, dumping out liquor. An older man picked up a hose and, according to one witness, said that he wanted to clean the liquor off the street, because children were playing nearby. In Edelman’s account, the man sprayed one of the cops. The police tackled him and shot him with a Taser. A brawl broke out, and bottles rained down on the cops. Officers sprayed mace, and three small children got it in their eyes. (Edelman told me that he was not aware that anyone had been maced, but acknowledged that it may have happened. “Could children have gotten mace in their eyes?” he said. “Unfortunately, yes.”)

The older man was arrested, and the cops drove away. After it grew dark, and the crowd began to thin out, Kevin Pratt, a photographer who lived nearby, noticed that the police had returned in force. Around the corner, a line of double-parked police vans stretched the length of the block. As the officers began moving toward the crowd, some of them pulling on gloves, Pratt turned on his camera. “Bunch of police officers about to come down there for y’all,” he said. A moment later, St. Fort walked over. He spoke with one of the cops, a sergeant, and the officers turned back around. “If they kept going down the block, there would have been a different situation,” Pratt told me. “There would have been, like, a riot.”

“Unfortunately, violence interrupters were not viewed as legitimate by many of my peers,” Derby St. Fort, the former second-in-command of the Seven-Three, said.Image: Dawit N. M.

This past June, Alicka Ampry-Samuel, Latrice Walker, and the U.S. Representatives Yvette Clarke and Hakeem Jeffries stood outside One Police Plaza, in downtown Manhattan, and called on the department to remove Edelman from the Seven-Three and fire his subordinate Vincent D’Andraia. In one video of D’Andraia shoving Dounya Zayer to the ground, which was viewed more than fourteen million times on Twitter, Edelman appeared to look at the injured protester without breaking stride. At One Police Plaza, Clarke noted that Edelman had taken “no action to deëscalate the situation” and “didn’t even stop to render aid.” Ampry-Samuel declared that he should not be given “a leadership position within the department anywhere.”

Gonzalez charged D’Andraia with assault—his case is still pending—and the police department transferred Edelman out of the Seventy-third Precinct. But the department gave Edelman what cops call a “soft landing.” He was made second-in-command of the Gun Violence Suppression Division, which investigates gun trafficking and what the department defines as “violent groups using firearms throughout the city.” One of his predecessors in the role had since become the division’s commander, replacing an assistant chief who would later become the chief of detectives.

In the weeks that followed Edelman’s reassignment, police and protesters continued to clash. On Long Island, a news site published photographs of police supporters marching with signs that read “Back the Blue” and “Blue Lives Matter.” One of the unmasked faces in the crowd appears to belong to Edelman.

In Brownsville, Ampry-Samuel sent the Mayor a list of three Black N.Y.P.D. executives as possible replacements for commander of the Seven-Three. One was St. Fort. She hoped that the department would allow him to continue to build on the relationships that he’d developed in Brownsville. Instead, his bosses moved him out of the neighborhood, ultimately placing him in charge of a precinct in Sheepshead Bay, a largely white, conservative neighborhood in South Brooklyn. Adams, the borough president, who is now running for Mayor, believed that the department’s top officials were upset that St. Fort had the “audacity” to try to build relationships within the community: “They looked at him and said, ‘Who do you think you are? Don’t buy into what we’re saying. Buy into what we believe.’ ”

Facing intense public pressure, the department chose another name from Ampry-Samuel’s list. Terrell Anderson, a deputy inspector, had grown up in Brownsville and in nearby Bedford-Stuyvesant, and still lived in the area. He had served as the executive officer of the Seven-Three under Edelman’s predecessor; together, the two Black cops had overseen a steep decline in shootings. In the months after his return, many residents reported that the police had been showing them more respect. “He grew up in this hood,” James, the violence interrupter, said. “He came back to help it. You can see it.”

Terrell Anderson, the Seven-Three’s new commander, said, of Brownsville, “The pervasive gun violence and poverty that plagues it . . . are a result of a design.”Image: Dawit N. M.

Anderson had spent many years as a plainclothes anti-crime officer and received several substantiated civilian complaints about improper searches. But, in recent years, his views on policing have evolved. Before taking over the Seven-Three, he commanded a neighboring precinct, in Canarsie; in March, 2020, nearly a dozen of his officers, responding to a reported shooting, ended up violently arresting a young man who allegedly had been smoking marijuana in a park. Last summer, Anderson told WNYC that the officers had failed to properly communicate with the suspect. “I’m O.K. with acknowledging what went wrong in that situation,” he said. “There is a culture in the N.Y.P.D. that needs to change, and part of that culture is ‘We know better.’ ”

In the Seven-Three, Anderson launched an experiment in community-led policing. For five days in December, he pulled his officers off a stretch of Mother Gaston Boulevard where Edelman had stationed cops around the clock. Representatives from city agencies and community organizations sat at tables along the sidewalk, connecting residents to sources of rental assistance and other services. Outside the nail salon where Kwesi Ashun had been killed by police, a team of violence interrupters kept watch over the block. One night, they got a call from someone in a gang; a member of the opposition had been spotted on the street. The violence interrupters defused the situation. Ultimately, no crimes were reported that week. “This was ‘defund the police’ in actuality,” Latrice Walker later told The City. “For the first time in a long time, the block felt safe.”

The department declined to grant me permission to speak with Anderson, but, in a brief e-mail, he explained his motives. “My love for Brownsville is immeasurable,” he wrote. “The pervasive gun violence and poverty that plagues it, and neighborhoods like it across this country, are a result of a design. I’ve chosen to seek to be on the side of history that disrupts that design. What and how it’s done must primarily come from the people most affected by it. Black people. America is indebted to us. Reparations are long overdue.”

Earlier this year, New York’s attorney general, Letitia James, sued the city, de Blasio, Shea, and Monahan over the department’s handling of the George Floyd protests. “There is no question that the N.Y.P.D. engaged in a pattern of excessive, brutal, and unlawful force,” she said. Soon afterward, de Blasio announced that he and Shea had decided to give communities more say in choosing their precinct commanders. Going forward, a panel of community members would interview several candidates for each open position, before making a recommendation to the police commissioner. The Mayor credited Eric Adams with bringing him the idea. Adams told me, “The reckoning over racially unjust policing forced by last summer’s protests underscored how necessary and urgent this change was.”

In an e-mail, a spokesman for the Mayor wrote that de Blasio was “elected on fighting for police reform, has pushed forward historic police reforms, and will continue to push for additional reforms in his final year in office.” He credited the Mayor with “ending the racist policy of Stop and Frisk in his first term” and referred to a state-mandated police-reform package that the City Council and the Mayor signed last month. The spokesman added, “Mayor de Blasio knows that police reform takes hard work and we’re not done yet.”

In March, Monahan and McEvoy both retired. Monahan was replaced by Rodney Harrison, who was one of several Black commanders to assume top leadership positions in the department since the beginning of the protests. At a press conference announcing Monahan’s departure, Harrison praised Monahan, saying to him, “We cannot keep this city safe unless we have that partnership with the people that we’re here to serve, and you had the vision.” De Blasio hailed Monahan as “one of the great architects of neighborhood policing,” and announced that he had appointed Monahan to serve as a senior adviser to a team responsible for managing the city’s recovery from the pandemic. “I need the very best, most talented, most experienced people to do this,” he said. Many in the department were baffled. “I like Terry,” the former department official said. “He’d be the first guy I’d get a drink with, but I would never have given him a role with that level of responsibility.” It soon emerged that both James and the Civilian Complaint Review Board were investigating Monahan’s conduct at the protests. At the start of the uprising, he had taken a knee with protesters. Three days later, according to a report by Human Rights Watch, he “appears to have commanded” a violent crackdown in the Bronx. (The N.Y.P.D. said that Monahan “was not in charge of any operational decisions” at the demonstration.)

On a recent afternoon, Ampry-Samuel reflected on her own efforts to keep the city safe. “As a Black woman, growing up where I did, I had to deal with a lot,” she said. “Every single job that I’ve had was so I could be in the position that I’m in.” The trouble, she said, was that she’d always had to contend with figures like Edelman—“just another white kid who has people looking out for him.” Ampry-Samuel is now running for speaker of the City Council; if she wins, she’ll be the first Black person to occupy the role. “In order for us to be able to breathe, we need leaders who want us to be able to breathe,” she said. “If we had leaders who really wanted to make a difference and see change, we wouldn’t be where we are today.”

This story was reported in partnership with Type Investigations.